Over the past five decades, the treatment of lupus nephritis (LN) has evolved from a disease with high morbidity and mortality to one characterized by improved patient and renal survival. Despite these advances, cure remains elusive and its management fraught with unacceptable short and long term treatment-related side effects. What are the reasons for this current state? In this article, we summarize the history of LN treatment and present some explanations for the roadblocks to more effective therapies.

Class III/IV lupus nephritis remains one of the most serious manifestations of lupus, associated with the development of end-stage renal disease (ESRD), mortality and significant treatment-related side effects and organ damage, including avascular necrosis and premature ovarian failure. Both complete and partial remissions are associated with better overall renal and patient survival.1 The current goal in the treatment of Class III/IV LN is to induce remission with a combination of corticosteroids and immunosuppressive agents, followed by a maintenance treatment phase of unclear duration incorporating little to no steroids along with an immunosuppressant.

Corticosteroids

In the early 1950s, Dubois et al reported on the use of corticosteroids in the treatment of 64 patients with active lupus, including patients with renal involvement; 30 patients were treated with various corticosteroid regimens, including ACTH, and 34 were untreated.2 Compared with untreated patients, corticosteroid use induced remission, provided a “Cushing state” was achieved. The 34 patients who were not treated with steroids all died from lupus. The authors reported that although there was no evidence that corticosteroids prolonged life expectancy at the time, steroid treatment induced remissions and concluded that “these agents are, at present, the most effective weapons available for the treatment of systemic lupus erythematosus.”

To this day, corticosteroids remain a standard, effective yet deleterious treatment for nearly all manifestations of lupus. Identifying safe and effective therapies that spare the use of steroids has been an important feature of clinical trials of therapeutics since.

Nitrogen Mustard

Dubois explored the use of nitrogen mustard for the treatment of 20 patients with lupus in 1954.3 Eleven patients had renal involvement, and eight of these patients demonstrated clinical improvement in terms of proteinuria and anasarca. Other publications, comprising small numbers of patients, also suggested that use of nitrogen mustard in addition to high-dose corticosteroids improved mortality rates in patients with less severe renal involvement.4

Immunosuppressive Agent + Steroids

In the 1970s and 1980s, results of the NIH cyclophosphamide protocol evolved under the leadership of John Decker, MD, demonstrating five-year renal survival rates of 60–80%.5 At this time, the benefits of the addition of an immunosuppressive agent to background steroids remained controversial, with some investigators arguing that the addition of potent immunosuppressive therapies was not supported by results from small clinical trials of patients with diffuse proliferative lupus nephritis.6,7

Results of the NIH study of intravenous cyclophosphamide used in combination with steroids vs. steroids alone or cyclophosphamide alone, along with a pooled analysis of clinical trials examining the use of steroids combined with immunosuppressants, laid the groundwork for the use of cyclophosphamide combined with corticosteroids as the heretofore gold standard for the treatment of this disease.8

In their landmark New England Journal of Medicine paper, the NIH investigators also showed that the superior renal survival benefits of combination intravenous cyclophosphamide and steroids vs. steroids alone or with azathioprine were realized only after 10–12 years, underscoring that long-term trials may be required to ascertain an effective treatment for LN.

ELN

Alternative regimens to the NIH cyclophosphamide protocol were motivated by significant toxicities observed in all arms of that study, with mortality being greatest in the cyclophosphamide monotherapy group (7%). Over the last decade or so, induction regimens using mycophenolate mofetil (MMF) or the “European Lupus Nephritis Protocol” (ELN), in which patients receive six fortnightly doses of 500 mg of cyclophosphamide, have yielded induction remission rates comparable to the “gold standard” NIH protocol, with less infection, death and malignancy.9,10

In addition to the treatment options informed by these trials, further knowledge regarding the importance of ethnicity and race affecting treatment response has also emerged, adding to the complexity of management. To date, clinical trials of targeted biological therapies combined with steroids and background immunosuppressive therapy have not improved on this gold standard in short-term studies. Although the success of the recent induction/remission trials of mycophenolate mofetil (MMF) and the ELN protocol have improved patient/renal outcomes, relapse rates remain high. What are the possible explanations for recurrent disease, progression to ESRD, lack of cure? Let’s review a case example, which will be used to highlight the limitations of our understanding regarding the pathogenesis, diagnosis and treatment of this disease.

Case Study

A 35-year-old woman of Albanian descent undergoing a work-up for infertility was found to have hypothyroidism. Treatment with levothyroxine was initiated, but within a few weeks, she noted widespread joint pain and fatigue. She was referred to a rheumatologist, and laboratory tests demonstrated an ANA of 1:1,280 (speckled), ESR 48 mm/hour, anti-dsDNA 1,130, Ro 130, Smith 22, low complements (C3, 36; C4, 2). The complete blood count (CBC), creatinine, urinalysis and antiphospholipid screen were normal. On physical examination she had arthritis.

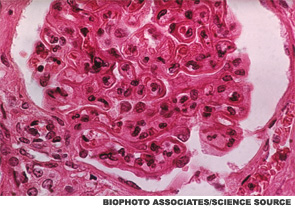

Hydroxychloroquine and naproxen controlled her symptoms for the next six months, and the anti-dsDNA and complement levels remained abnormal during this time. Microscopic hematuria along with 1 gram of urinary protein excretion was noted and confirmed on routine follow-up in the absence of symptoms. The serum creatinine and blood pressure were normal. Renal biopsy showed global, active diffuse proliferative nephritis (WHO Class IV), with an activity index of 13/24 and a chronicity index of 0/12; wire loops and crescent formation were seen. Pulse steroids followed by prednisone 1 mg/kg and MMF 3,000 mg/day were prescribed.

A year later, the renal disease had remitted, with preservation of renal function, normalization of serum complements and dsDNA. Prednisone was stopped and azathioprine substituted for MMF because the patient wanted to become pregnant.

Renal and extrarenal manifestations remained in remission for the next three years, during which she became pregnant and delivered a healthy daughter. Azathioprine was continued throughout the pregnancy and stopped at the patient’s request when she began breastfeeding. Surveillance serological studies during the pregnancy showed modest elevations of the dsDNA, intermittently low complements, without any clinical manifestations or other laboratory abnormalities.

Eighteen months following delivery, microscopic hematuria, along with an increase of the urinary protein excretion to 700 mg/24 hr, was noted on routine testing in the absence of symptoms, rise in blood pressure or worsening serum creatinine. Prednisone 20 mg/day and MMF 3,000 mg/day were restarted, with normalization of all urinary findings, preservation of GFR and continued modest elevations in repeated measurements of the anti-dsDNA and hypocomplementemia.

Limitations in Diagnosis

- Elevated anti-dsDNA often suggests a diagnosis of SLE, but it is an inadequate predictor of disease onset or flare. In the 1960s, it was shown that a rise in anti-dsDNA Ab levels along with a fall in complement levels predicted a flare of lupus nephritis.11 This correlation has held up fairly well, but not perfectly, and clearly something better is needed. This is illustrated in the case example, in which some correlation between anti-dsDNA and active nephritis was observed.

- No accurate peripheral blood cell and immune parameter predicts adequately intrarenal immunopathology.

- There are no reliable urinary biomarkers of active inflammatory intrarenal disease and renal fibrosis.

- There is a modest correlation between high anti-C1q antibodies and the development of LN (these antibodies were not measured in this patient).

Limitations in Our Understanding of Pathogenesis of LN

- What is it that determines which lupus patients develop renal disease?

- What is it that determines which lupus patients develop WHO Classes 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, and why then do some patients switch classes?

- Why do patients with LN tend to make complement fixing antibodies to dsDNA more so than patients without LN?

- Which of the genes that have been associated with lupus lead to LN and its variants (e.g., WHO Classes 2–6)?

- Are murine models of lupus applicable to human SLE? CTLA4-Ig acts synergistically to halt LN in murine models of lupus, but trials of abatacept and cyclophosphamide in humans showed no added benefit of abatacept.12 It’s not known whether features of trial design or intrinsic differences between human and animal disease accounted for this observation.

- What are the inflammatory pathways that lead to fibrosis, the pathologic determinant of ESRD, and can the transition from inflammation to fibrosis be interrupted?

Limitations in Treatment

- Current clinical trials are powered to detect primary outcome measures over short durations (6–12 months), which may not be clinically meaningful over the long term. (The index patient had an initial clinical response, but recurrence within four years of an apparent remission.) The NIH cyclophosphamide trial showed that it took about 10 years to clearly demonstrate that steroids plus cyclophosphamide was better than steroids alone for the prevention of renal failure.

- Racial and ethnic characteristics affect the responses to MMF; among black and Latino patients in the Aspreva Lupus Management (ALMS) study, 60% responded to MMF compared with 39% of patients treated with cyclophosphamide.13

- The ELN protocol was initially studied in Caucasians and, thus, not generalizable to patients of Hispanic, black or Asian descent, who are especially prone to LN. Insights regarding the comparable efficacy of this regimen in blacks and Hispanics with Caucasians was gleaned in the randomized trial of abatacept combined with the European cyclophosphamide regimen vs. placebo combined with the European regimen in patients with Class III/IV nephritis.14

- Murine models of disease have demonstrated a response to biologics (e.g., abatacept with CTX), which was not seen in humans, suggesting that more effective therapies might be better developed by a deeper understanding of human pathology.

- Which medication(s) are best to control blood pressure?

- What is the mechanism of action of ACE/ARB medications in reversing proteinuria? Answers to this question, as well as the preceding question, are largely extrapolated from studies of ACE inhibitors in diabetics and populations other than lupus.

- The appropriate duration of maintenance treatment with steroids, immunosuppressives and antihypertensives is unclear (index patient had renal flare within 18 months of stopping azathioprine).

- What treatment/medications will prevent renal fibrosis, prevent progression of fibrosis and reverse renal fibrosis?

The incremental progress in renal and patient survival amongst patients with LN over the past 60 years is related to effective treatment regimens informed by studies showing the remittive effects of corticosteroids alone followed by trials of immunosuppressive agents combined with steroids.

To date, studies of alternative regimens to intravenous cyclophosphamide, such as MMF and the ELN protocol, in the past decade have demonstrated comparable efficacy to intravenous cyclophosphamide with reduced treatment-related comorbidities. The addition of biologic therapies to these regimens—in particular rituximab and abatacept—assessed over relatively short periods, has not resulted in improvements above that observed with the NIH cyclophosphamide protocol. Improvements in efficacy have not paralleled improvements in treatment-related morbidities.

Going forward, significant improvements in treatment efficacy will not only be partially realized by clinical trials, but also by a deeper understanding of therapeutics directed against specific features of human pathology.

Elena M. Massarotti, MD, is an associate professor of medicine at Harvard Medical School and director of clinical trials in the Lupus Center at Brigham and Women’s Hospital. She divides her professional time between direct patient care, clinical research in the areas of therapeutics of lupus and rheumatoid arthritis, and medical education.

Peter H. Schur, MD, is professor of medicine at Harvard Medical School, senior physician at Brigham and Women’s Hospital, medical director of the Brigham and Women’s Hospital Clinical Immunology Laboratory, editor of UpToDate in Rheumatology, and emeritus director of the Lupus Center at Brigham and Women’s Hospital, where he maintains an active clinical practice, continues to mentor trainees and teaches medical students.

Acknowledgment: The authors wish to thank Dr. Richard Furie for his helpful comments.

References

- Chen YE, Korbet SM, Katz RS, et al. Value of a complete or partial remission in severe lupus nephritis. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2008 Jan;3(1):46–53.

- Dubois EL, Commons RR, Starr P, et al. Corticotropin and cortisone treatment for systemic lupus erythematosus. J Am Med Assoc. 1952 Jul 12;149(11):995–1002.

- Dubois EL. Nitrogen mustard in the treatment of systemic lupus erythematosus. AMA Arch Intern Med. 1954 May;93(5):667–672.

- Dillard MG, Dujovne I, Pollak VE, et al. The effect of treatment with prednisone and nitrogen mustard on the renal lesions and life span of patients with lupus nephritis. Nephron. 1973;10(5):273–291.

- Austin HA, Klippel JH, Balow JE, et al. Therapy of lupus nephritis. Controlled trial of prednisone and cytotoxic drugs. N Engl J Med. 1986 Mar 6;314(10):614–619.

- Wagner L. Immunosuppressive agents in lupus nephritis: A critical analysis. Medicine (Baltimore). 1976 May;55(3):239–250

- Donadio JV Jr, Holley KE, Wagoner RD, et al. Treatment of lupus nephritis with prednisone and combined prednisone and azathioprine. Ann Intern Med. 1972 Dec;77(6):829–835.

- Felson DT, Anderson J. Evidence for the superiority of immunosuppressive drugs and prednisone over prednisone alone in lupus nephritis—Results of a pooled analysis. N Engl J Med. 1984 Dec 13;311(24):1528–1533.

- Ginzler EM, Dooley MA, Aranow C, et al. Mycophenolate mofetil or intravenous cyclophosphamide for lupus nephritis. N Engl J Med. 2005 Nov 24;353(21):2219–2228.

- Houssiau FA, Vasconcelos C, D’Cruz D, et al. Immunosuppressive therapy in lupus nephritis. The Euro-Lupus Nephritis Trial, a randomized trial of low-dose versus high-dose intravenous cyclophophamide. Arthritis Rheum. 2002 Aug;46(8):2121–2231.

- Schur PH, Sandson J. Immunologic factors and clinical activity in systemic lupus erythematosus. N Engl J Med. 1968 Mar 7;278(10):533–538.

- Daikh DI, Wofsy D. Cutting edge: Reversal of murine lupus nephritis with CTLA4Ig and cyclophosphamide. J Immunol. 2001 Mar 1;166(5):2913–2916.

- Appel GB, Contreras G, Dooley MA, et al. Mycophenolate mofetil versus cyclophosphamide for induction treatment of lupus nephritis. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2009 May;20(5):1103–1112.

- Wofsy D, Askanase A, Cagnoli PC, et al. Treatment of lupus nephritis with abatacept plus low-dose cyclophophamide followed by azathioprine (the Euro-Lupus Regimen): Twenty-four week data from a double-blind controlled study. Arthritis Rheum. 2013;65(S10):884.