Philadelphia—Discovery of a leptin–serotonin pathway to regulate appetite and bone mass accrual is providing valuable insight into bone disease and may open new pathways to therapy.

Gerard Karsenty, MD, PhD, chair of the department of genetics and development at Columbia University’s College of Physicians and Surgeons in New York, said that this research is a good example of how physiology “has been more changed by mouse genetics than any other field.” He delivered the Hench Society Lecture here at the ACR/ARHP Annual Scientific Meeting in October 2009. Each year, the Hench Society Lecture honors the contributions of Philip S. Hench, MD, the co-winner of the 1950 Nobel Prize in Medicine, for his work on cortisone.

In his lecture, Dr. Karsenty reviewed several steps in the research with mouse models that were published in the journal Cell.1 This research, he said, underscored the concept that, “for every physiological function, there is more than one organ involved.”

Although clinical applications await future investigation, the current research adds to understanding of the apparent association of obesity with a lower incidence of osteoporosis. It may open up new avenues for research into the development of osteoporosis in people treated with selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs). Dr. Karsenty noted two important clinical observations that prompted this avenue of research: “Obesity invariably follows gonadal failure, and obesity protects from osteoporosis.”

Understanding Bone Remodeling

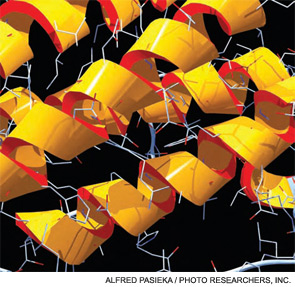

Research conducted by Dr. Karsenty and colleagues in 2007 had identified the skeleton as an organ of the endocrine system that helps regulate glucose metabolism. In that research, also published in Cell, they reported that bone cells release osteocalcin.2 “By revealing that the skeleton exerts endocrine regulation of sugar homeostasis, this study expands the biological importance of this organ and our understanding of energy metabolism,” they wrote.

According to Dr. Karsenty’s presentation at the meeting, there are two defining features of the physiology of the skeletal system. One is that the skeleton, with the skin and muscle, is an organ covering the largest surface of the body. Additionally, and somewhat surprisingly, bone contains a cell, the osteoclast, whose main function is to constantly destroy bone.

It is now understood that leptin regulates the homeostatic function of bone remodeling in humans and in mice, a process that includes both bone resorption and bone formation. The original purpose of bone remodeling during evolution was the repair of micro and macro damage, or fractures. “It was a survival function,” Dr. Karsenty said.