As a dermatologist/internist with a career-long subspecialty interest in the cutaneous manifestations of the rheumatic diseases, I found the case of refractory acute cutaneous lupus by Samantha C. Shapiro, MD, in the June 2022 issue of The Rheumatologist intriguing in several ways, and I felt my perspectives on this case might provide additional educational value to the rheumatologist readership.

As a dermatologist/internist with a career-long subspecialty interest in the cutaneous manifestations of the rheumatic diseases, I found the case of refractory acute cutaneous lupus by Samantha C. Shapiro, MD, in the June 2022 issue of The Rheumatologist intriguing in several ways, and I felt my perspectives on this case might provide additional educational value to the rheumatologist readership.

Diagnosis & Classification

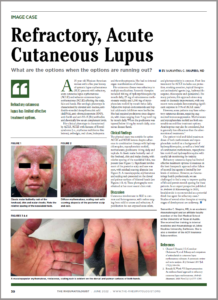

The clinical photos of the patient being discussed suggest a generalized inflammatory skin disorder (i.e., skin lesions both above and below the neck) occurring in the context of a five-year history of systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE). However, the historical duration of the skin changes was not given. The patient’s serologic phenotype was very active at the time of presentation, including anti-double-stranded DNA, RNP, Sm and Ro/SS-A autoantibodies, as well as chronically low serum complement levels. In addition, the patient had leukopenia and thrombocytopenia. However, it is stated that the patient had no internal SLE target-organ disease manifestations.

Had a lesional skin biopsy been performed in this case, it could be presumed it would have demonstrated an interface dermatitis, as would be expected for any form of lupus-specific skin disease. Biopsies of acute cutaneous lupus erythematosus (ACLE) and subacute cutaneous lupus erythematosus (SCLE) lesions have a lymphoid cell-rich inflammatory infiltrate focused at the dermal-epidermal junction with damage to the epidermal basal cell layer (i.e., an interface dermatitis). In addition to displaying an interface dermatitis, biopsies of discoid SLE lesions can also show deep reticular dermis inflammation and damaged skin appendages, such as hair follicles and sweat glands, and result in atrophic scarring. This deeper dermal inflammation in discoid SLE lesions can produce clinical induration, which is characteristically not seen in either ACLE or SCLE lesions.

In the case discussion, it was suggested the skin findings consisted of a combination of ACLE and SCLE lesions. In the early epidemiologic studies of SCLE, it was recognized that SCLE can overlap with either ACLE or classic discoid lupus erythematosus in approximately 20% of cases.1

The case discussion mentioned scarring alopecia on the posterior scalp of this patient. Neither ACLE nor SCLE produce confluent scarring alopecia of the scalp, nor scarring on other parts of the body. In addition, SCLE lesions are characteristically observed on the trunk, with sparing of the central face. These aspects, plus the prominent papulosquamous scale on the skin lesions of this patient, raise the possibility that she could be suffering from a generalized form of classical discoid lupus erythematosus rather than an overlap of ACLE and SCLE. Although uncommon, discoid lupus erythematosus can involve the “butterfly” distribution of facial skin. And generalized classical discoid lupus erythematosus can, at times, be more refractory to treatment than either ACLE or SCLE.

The case discussion also mentioned the patient had cutaneous changes suggestive of Rowell’s syndrome (i.e., erythema multiforme-like skin lesions occurring in context of anti-Ro/SS-A and/or anti-La/SS-B autoantibodies). Presumably that was a reference to the annular palmar skin lesions that were shown in one of the photos of this patient. However, on rare occasion, annular discoid lupus erythematosus skin lesions can preferentially localize to the palmar skin.

Another cause for refractory cutaneous lupus erythematosus is unrecognized drug-induced/drug-exacerbated cutaneous lupus erythematosus. SCLE is now known to commonly be triggered by delayed-in-time hypersensitivity reactions to members of a large number of prescription drug classes (e.g., thiazide diuretics, calcium channel blockers, ACE inhibitors, allylamine antifungals such as terbinafine, protein pump inhibitors, oncologic drugs and others). A list of drugs this patient was taking at the time of lupus erythematosus skin disease onset was not provided in the case summary. In addition to prescription drugs, one must consider certain over-the-counter drugs. As an example, physicians who start patients on prednisone often have the patient start taking an over-the-counter protein pump inhibitor, such as omeprazole, to minimize gastrointestinal side effects due to prednisone. Protein pump inhibitors are one of the more common drug classes that can induce SCLE. However, drug-inducted discoid lupus erythematosus is much less common, if existent at all. Some such published cases of druginduced discoid lupus erythematosus appear to, in fact, be drug-induced SCLE cases.

It is somewhat anomalous that a patient with such active SLE serologies, leukopenia, thrombocytopenia and persistent hypocomplementemia would have no evidence of internal organ SLE activity or damage. In the context of anti-double-stranded DNA autoantibodies and hypocomplementemia, SLE patients have traditionally been thought to be at increased risk for lupus nephritis. One setting in which this SLE patient’s clinical constellation might occur would be in the setting of a genetic complement deficiency state.

Homozygous genetic deficiency of C1q, the first component of the classical complement pathway, is one of the strongest monogenetic associations of SLE. And, C1q-deficient SLE patients frequently exhibit photosensitive forms of cutaneous lupus erythematosus. In addition, genetic deficiency of the C2 and C4 complement components has been associated with SCLE and possibly with discoid lupus erythematosus as well. One might postulate that genetic deficiency of an early classical pathway complement component could be a risk factor for treatment-refractory cutaneous lupus erythematosus. Familial discoid lupus erythematosus patients with heterozygous C2 deficiency have been reported to have a clinical phenotype similar to that of the patient described by Dr. Shapiro.2 However, the limited anecdotal published literature in this area does not fully support nor refute this hypothesis.

Refractoriness

Over the past four decades I have had many cutaneous lupus erythematosus patients referred to me for “hydroxychloroquine resistance.” A good proportion of these patients were found to have been truly resistant to antimalarial monotherapy with hydroxychloroquine. Many of those patients responded to combination antimalarial therapy by adding quinacrine to the hydroxychloroquine for an appropriate period of time. Unfortunately, FDA regulatory actions have resulted in compounded quinacrine not being available on the U.S. market starting in 2016. However, quinacrine recently became available from certain compounding pharmacies that have been unwilling to divulge their source(s). These compounding pharmacies are offering quinacrine at a much higher price, making it unavailable to many patients as coverage of compounded medications by U.S. healthcare insurance organizations is spotty at best. As a result, patients are required to pay the full costs of quinacrine out of pocket more often than not.

It has also been suggested that some patients with cutaneous lupus erythematosus respond to chloroquine when they have not responded to hydroxychloroquine. For unknown reasons, cigarette smoking has been observed not only to be associated with discoid lupus erythematosus, but can also blunt the clinical effectiveness of hydroxychloroquine therapy in cutaneous lupus erythematosus. This was mentioned in the discussion of the case in question. However, it was not specifically stated whether this patient previously or currently smoked cigarettes. Another clinical setting in which hydroxychloroquine might not produce clinical benefit for cutaneous lupus erythematosus is when patients are noncompliant in taking the drug. It has been reported that noncompliance in taking hydroxychloroquine accounted for a significant percentage of SLE patients having sub-therapeutic blood levels of hydroxychloroquine.3

Until recently, assays of hydroxychloroquine blood levels have required assay techniques such as high-performance liquid chromatography with fluorometric detection that are not compatible with modern high-volume commercial labs. However, progress has recently been made with a capillary electrophoresis-based methodology that might be more compatible with the requirements of modern high-volume commercial testing labs.4

Dr. Shapiro concluded the discussion of modern targeted therapy for refractory cutaneous lupus erythematosus with the suggestion that lenalidomide might be considered. Lenalidomide is a derivative of thalidomide thought possibly to have less severe side effects than thalidomide. There is a body of published historical evidence demonstrating that thalidomide can have significant clinical benefit for patients with refractory, active, inflammatory cutaneous lupus erythematosus. Modern evidence suggests that lenalidomide can have a similar benefit for refractory cutaneous lupus erythematosus. The time of onset of clinical benefit of these drugs is quite rapid. However, they both appear to induce short-term anti-inflammatory effects in cutaneous lupus erythematosus rather than long-term remission induction. There is some evidence that SCLE patients can go into long-term remission or convert to milder disease after stopping thalidomide/lenalidomide. This has been reported for SCLE than discoid lupus erythematosus.5

Another major problem with such drugs as lenalidomide and thalidomide is their exorbitant costs. Both thalidomide and lenalidomide have FDA-approved indications in cancer therapy. As such, their costs are extremely high in the U.S. In 2022, lenalidomide cost was ~$294,000 per year for the average person in the U.S. Because neither thalidomide nor lenalidomide has been FDA approved for either SLE or cutaneous lupus erythematosus, it would be difficult to convince a patient’s commercial medical insurer to cover the high costs of these drugs. However, if a lower income patient meets the company’s patient assistance program criteria, they could receive the drugs from the company without cost.

Other drugs that might be of benefit to refractory cutaneous lupus erythematosus include monthly high-dose intravenous immunoglobulin infusion (IVIG), belimumab, JAK/STAT intracellular signaling pathway inhibitors (e.g., tofacitinib, ruxolitinib, baricitinib), and interferon receptor inhibitors (e.g., anifrolumab). Tyk intracellular signaling inhibitors, monoclonal antibodies targeting plasmacytoid dendritic cells (e.g., anti-BDCA2, anti-ILT7) and cGAS-STING intracellular signaling inhibitors could be of potential clinical benefit for refractory cutaneous lupus erythematosus in the future.

While often underappreciated, comparative healthcare quality-of-life studies have shown that chronic skin disease is among the most debilitating of all medical illnesses. As space here is limited, the interested reader can find additional literature citations to relevant points of discussion in the text above in several recently published reviews on

this subject.6

Richard D. Sontheimer, MD, Professor (Clinical) of Dermatology and Board Certified in Internal Medicine, Dermatology, Dermatologic Immunology Department of Dermatology Spencer Fox Eccles School of Medicine, University of Utah.

References

- Sontheimer RD. Subacute cutaneous lupus erythematosus: A decade’s perspective. Med Clin North Am. 1989 Sep;73(5):1073–1090.

- Belin DC, Bordwell BJ, Einarson ME, et al. Familial discoid lupus erythematosus associated with heterozygote C2 deficiency. Arthritis Rheum. 1980 Aug;23(8):898–903.

- Costedoat-Chalumeau N, Amoura Z, Hulot JS, Hammoud HA, et al. Low blood concentration of hydroxychloroquine is a marker for and predictor of disease exacerbations in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus. Arthritis Rheum. 2006 Oct;54(10):3284–3290.

- Sotgia S, Zinellu A, Mundula N, et al. A capillary electrophoresis-based method for the measurement of hydroxychloroquine and its active metabolite desethyl hydroxychloroquine in whole blood in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Molecules. 2022 Jun 17;27(12):3901.

- Cortés-Hernández J, Torres-Salido M, Castro-Marrero J, et al. Thalidomide in the treatment of refractory cutaneous lupus erythematosus: prognostic factors of clinical outcome. Br J Dermatol. 2012 Mar;166(3):616–623.

- Yan D, Borucki R, Sontheimer RD, Werth VP. Candidate drug replacements for quinacrine in cutaneous lupus erythematosus. Lupus Sci Med. 2020 Oct;7(1):e000430.

Author Response

Thank you so much for your interest in this case.

Skin changes had been present for a total of five years, at which time I assumed care of the patient. A dermatologist had seen the patient a few times and concluded the patient had ACLE and SCLE with features of Rowell’s syndrome based on physical exam findings. Skin biopsy was deferred given the high likelihood of cutaneous lupus erythematosus and cost to the patient, who was paying out of pocket for her care. I agree that classic discoid lupus erythematosus is another consideration here, and I very much appreciate your educational discussion.

Your point about refractory cutaneous lupus erythematosus due to an unrecognized drug reaction is another worthy teaching pearl. This patient was not routinely taking any prescription or over-the-counter medications before or during her clinical course, aside from those prescribed for management of SLE.

I, too, was continuously surprised by her lack of end-organ manifestations of disease despite years of active SLE serologies and severe cutaneous lupus erythematosus. Urine studies were closely monitored and consistently normal. A genetic complement deficiency state could indeed explain her SLE variant. Thank you for turning our attention to this interesting entity.

“Hydroxychloroquine resistance” is another valid point. The quotations here are deliberate because compliance plays a well-documented role in patients’ “unresponsive to treatment,” as your letter aptly cited. Hydroxychloroquine blood levels were deferred given the associated cost, but I do believe the patient was compliant with her medications. We communicated frequently via electronic messages, and she was always forthcoming about her need for refills, as well as cutaneous flares. The addition of quinacrine was suggested by dermatology colleagues, but was price prohibitive. The patient did not previously or currently smoke.

Regarding therapeutic options for refractory disease, I agree with your diverse suggestions. I’m hopeful new therapies and additional data will provide better answers for these patients in the future. Cost, as you mentioned, continues to be an issue for many.

It’s worth noting that the patient’s care was not only complicated by severe disease, but limited access. She did not have health insurance. Her family’s gross income was too high to qualify for local sliding scale programs, but too low to afford commercial or Marketplace coverage. And even if she had qualified for a local program, biologics and synthetic small molecules wouldn’t be covered.1 She was not approved for lenalidomide’s patient assistance program (PAP). She is currently in the process of applying for tofacitinib via PAP. Despite my clinic’s extensive experience assisting patients with PAP applications, she is yet to receive the medication.2

With gratitude,

Samantha C. Shapiro, MD, Affiliate Faculty, Division of Rheumatology, Dell Medical School at the University of Texas at Austin.

References

- Shapiro SC. Lessons from caring for the underinsured & uninsured. The Rheumatologist. 2022 Feb 17.

- Shapiro SC. The ins & outs of patient assistance programs. The Rheumatologist. 2022 Mar 3.