Review the case…

A. Lipodermatosclerosis

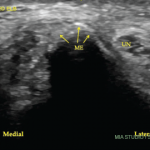

Historically, lipodermatosclerosis (LDS) was called “hypodermitis sclerodermiformis,” and terms such as pseudoscleroderma were used because of its indurated, hyperpigmented appearance, present on the distal lower extremity.1 Lipodermatosclerosis may best be described as a “sclerosing panniculitis,” found most commonly on the medial leg above just proximal to the medial malleolus. An acute and chronic phase occurs. Early, acute LDS may resemble a tender area of cellulitis or thrombophlebitis in the setting of lower extremity stasis, but its location, persistence, and indurated/ “bound-down” quality helps distinguish it from other entities. Chronic LDS is hyperpigmented, quite indurated and contracted, and may give the characteristic “inverted wine bottle” appearance. Ulceration is a complication and may occur in up to 13% of cases.2 It is generally a clinical diagnosis and caution should be taken if performing a biopsy confirmation because chronic nonhealing ulcerations may ensue. Doppler assessment of the lower-extremity venous system is often advised. The most conventional treatment involves regular use of compression stockings. Oral stanozolol, a testosterone derivative with fibrinolytic activity, has been shown superior to placebo in a small, double-blind, crossover trial and in an open trial by Dakovic et al for treating LDS.2,3 Intralesional steroids, topical steroids, topical capsaicin, oral pentoxifylline, and venous surgical intervention have been used as well.1

In the patient presented in our case, regular use of compression stockings (30–40 mmHg) as well as potent topical steroid use resulted in resolution of symptoms and softening of the skin in the affected area, along with hair regrowth locally (see Figure 2), which may signal improvement in dermal fibrosis, allowing hair follicle regrowth.

Discussion of Other Choices

B. Morphea: Of the subsets of clinical morphea, this case would be most consistent with an isolated plaque of morphea. Typically in its inflammatory stage, morphea has an erythematous-violaceous border around a sclerotic appearing central area of skin, which, over time, centrally tends to lose its inflammatory component. In the setting of this patient’s venous stasis changes as well as the isolated and characteristic location of the lesion, lipodermatosclerosis is a much more likely diagnosis. Biopsy is able to distinguish these entities, but is not necessary in this case.

C. Cellulitis: LDS is often initially mistaken for an area of early lower extremity cellulitis. A lack of response to antibiotic therapy, lack of systemic symptoms including fever, lack of rapid progression in size and area of involvement, a background of venous stasis disease, and two- to three-month duration make cellulitis much less likely.

D. Necrobiosis lipoidica (diabeticorum) (NLD): NLD is a disorder of collagen degeneration associated with diabetes, but it can occur in the absence of underlying diabetes. This diagnosis would distinguish itself over time. Lesions begin with erythema and tend to occur more frequently on the lower extremities. They evolve into shiny, somewhat atrophic yellowish plaques, which may ulcerate. This is different than the fibrotic, bound-down appearance of lipodermatosclerosis seen in our patient.

E. Limited systemic sclerosis: The asymmetric nature of the lesion, its characteristic location, and absence of other systemic signs and symptoms make this diagnosis much less likely, although a patient with limited systemic sclerosis has been described who developed LDS.1

Sources:

- Miteva M, Romanelli P, Kirsner RS. Lipodermatosclerosis. Dermatol Ther. 2010;23:375-388.

- Burnand K, Clemenson G, Morland M, Jarrett PE, Browse NL. Venous lipodermatosclerosis: Treatment by fibrinolytic enhancement and elastic compression. BMJ. 1980;280:7-11.

- Dakovic Z, Vesic S, Vukovic J, Medenica LJ, Pavlovic MD. Acute lipodermatosclerosis: An open clinical trial of stanozolol in patients unable to sustain compression therapy. Dermatol Online J. 2008;14:1

Dr. Merola is an instructor in the Department of Dermatology at Harvard Medical School and a fellow in the rheumatology division at Brigham and Women’s Hospital, both in Boston. He is the assistant program director for the Combined Medicine-Dermatology training program and a diplomat of the American Board of Dermatology and the American Board of Internal Medicine.