Take the Dermatology Case Challenge.

B: Sweet’s syndrome (drug-induced)

Sweet’s syndrome, also known as acute febrile neutrophilic dermatosis, is characterized by fever, peripheral neutrophilia, and multiple asymmetric diffuse edematous, erythematous skin lesions. The lesions may be so edematous, in fact, as to have a “pseudovesicular” appearance on their surface and may contain a subtle pustular component from the abundance of neutrophils present in the lesions. A deep variant involving adipose tissue is known as subcutaneous Sweet’s syndrome and has the deep, tender nodular appearance of other panniculitides clinically (erythema nodosum-like lesions). Malignancy-associated Sweet’s syndrome may present in a bullous or ulcerated variant mimicking pyoderma gangrenosum. Other extracutaneous manifestations of Sweet’s occur less frequently and may affect almost any organ system including, for example, culture-negative pulmonary neutrophilic infiltrates.1

Sweet’s generally presents in three scenarios: idiopathic or “classic,” malignancy-associated, and drug-induced. In our patient, the initiation of azathioprine as maintenance therapy for her vasculitis correlated with the onset of the lesions and the lesions resolved with discontinuation and a brief oral steroid taper. Drug-induced Sweet’s was first reported in 1986 in a patient taking trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole; however, the most frequent cause is the administration of granulocyte-colony stimulating factor.2 There are numerous reports of azathioprine-induced Sweet’s syndrome, with discontinuation leading to resolution and recurrence upon rechallenge.3-5

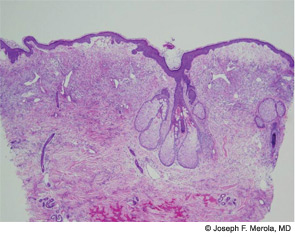

The histopathologic findings of Sweet’s on biopsy include a diffuse, dense infiltrate of mature neutrophils with significant papillary dermal edema (correlating with the “juicy” edematous plaques of Sweet’s). Leukocytoclasia may be present but vasculitic changes are usually absent. These findings can also be observed secondary to an infectious agent, so the work-up should always include tissue for bacterial, fungal, mycobacterial, and perhaps even viral cultures. Further systemic work-up for extracutaneous manifestations is driven largely by symptoms and a work-up for underlying malignancy should be considered in the absence of an otherwise clear etiology.6 Criteria for drug-induced Sweet’s exist as suggested by Walker and Cohen.7

First-line management is via treatment of any underlying condition (e.g., malignancy) and discontinuation of offending medication in the case of drug-induced variants. Topical, intralesional, and oral corticosteroids are the mainstay of treatment. The condition is exquisitely sensitive to steroids, making this one of the diagnostic criteria. Other antineutrophilic agents such as colchicine and dapsone have been used, as well as potassium iodide. A host of second- and third-line therapies exist as reported in case reports and small series for recalcitrant disease.1

Discussion of Other Choices

A. Bacterial Sepsis: The diffuse, randomly scattered erythematous nodules and plaques of Sweet’s should prompt initial concern for disseminated bacterial infection in the febrile patient. Appropriate infectious disease work-up is crucial to what is often a diagnosis of exclusion. As mentioned above, the histopathologic features on biopsy of sheets of neutrophils (together with the absence of a predominant vasculitic change) should immediately invoke concern for infection, and thus tissue culture of biopsy material is an important diagnostic element in suspected cases. A febrile patient with culture-negative samples and abrupt-onset lesions clinically consistent with those of Sweet’s in the right clinical context should prompt consideration of the diagnosis. An alternative diagnosis of infection always remains a primary concern in these patients.

C. Urticaria: The edematous nature of the Sweet’s lesion may, at times, resemble those of robust urticarial lesions; however, there are many clinical features to help distinguish these entities. The lesions of urticaria will migrate over time (excluding the case of urticarial vasculitis) with areas of clearing developing hours after mast cell degranulation has occurred locally. Symptoms such as pruritus further help to differentiate lesions. Systemic symptoms including fever do not occur in common urticaria, although they may be present in urticarial vasculitis and the urticarial eruptions of serum sickness-like reactions, potentially occurring together with arthralgias, malaise, a subtle purpuric component to lesions, and the possible finding of an active urine sediment with renal involvement. Histopathologic evaluation of skin biopsies in these entities would readily distinguish them from Sweet’s syndrome.

D. Systemic Mycoses/Deep Fungal Infections: Deep fungal infections may present as tender, scattered erythematous nodules and/or plaques. The image of these nodular lesions should invoke a differential diagnosis which includes panniculitides, including the septal panniculitis of the erythema nodosum; small–medium vessel vasculitides involving the skin, such as cutaneous polyarteritis nodosa; subcutaneous Sweet’s syndrome as described above; and infections, particularly deep fungal infections. In the proper clinical context, such as the immunocompromised individual, fungal infection should be considered and therefore a work-up including biopsy for fungal stains and culture should be performed.

E. Recurrent ANCA-vasculitis with cutaneous involvement: While recurrence of the patient’s disease could certainly present in the skin, her lesions are not typical of a small–medium vessel vasculitis. We would expect the primary lesion in that case to be nonblanching, most classically palpable purpuric lesions of small vessel vasculitis, although some morphologic variation might exist. The biopsy would demonstrate vasculitic changes (fibrinoid necrosis of the vessel wall, leukocytoclasia, extravasated red blood cells, and, in the case of granulomatous polyangiitis, a granulomatous or necrotizing component, as well) if the patient had recurrent disease involving her skin, whereas Sweet’s rarely demonstrates features of vasculitis and would have a much more dramatic neutrophilic infiltrate and papillary dermal edema.

References

- Cohen PR. Sweet’s syndrome—a comprehensive review of an acute febrile neutrophilic dermatosis. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2007;2:34.

- Su WPD, Liu HNH. Diagnostic criteria for Sweet’s syndrome. Cutis. 1986;37:167-174.

- El-Azhary RA, Brunner KL, Gibson, LE. Sweet’s syndrome as a manifestation of azathioprine hypersensitivity. Mayo Clin Proc. 2008;83:1026-1030.

- Paoluzi OA, Crispino P, Amantea A, et al. Diffuse febrile dermatosis in a patient with active ulcerative colitis under treatment with steroids and azathioprine: A case of Sweet’s syndrome. Case report and review of the literature. Dig Liver Dis. 2004;36:361-366.

- Yiasemides E, Thom G. Azathioprine hypersensitivity presenting as a neutrophilic dermatosis in a man with ulcerative colitis. Astralas J Dermatol. 2009;50:48-51.

- Cohen PR, Kurzrock R. Sweet’s syndrome and cancer. Clin Dermatol. 1993;11:149-157.

- Walker DC, Cohen PR. Trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole-associated acute febrile neutrophilic dermatoses: Case report and review of drug-induced Sweet’s syndrome. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1996;34:918-923.

Dr. Merola is an instructor in the department of dermatology at Harvard Medical School and a fellow in the rheumatology division at Brigham and Women’s Hospital, both in Boston. He is assistant program director for the Combined Medicine-Dermatology training program and a diplomat of the American Board of Dermatology and the American Board of Internal Medicine. Dr. Ramirez is a fellow in the rheumatology division at Brigham and Women’s Hospital and a diplomat of the American Board of Internal Medicine.