EF is usually a disease of middle-aged or older adults, but there are reports in children and young adults. It presents with symmetric erythema, swelling and induration of both the upper and lower extremities, which is often accompanied by pain or myalgias. Symptoms can be isolated to the upper or lower extremities, can be unilateral, and can rarely involve the trunk. As the underlying deep sclerosis progresses, patients can develop a depression along the venous channels, called the groove sign, and/or a pseudocellulite appearance of the skin. These findings are especially apparent on exam when the limb is abducted. Sclerosis and fibrosis overlying joints can cause contractures, which are the most common cause of morbidity. Thirty to forty-five percent of patients with EF can have concurrent plaque morphea. Inflammatory arthritis and carpal tunnel syndrome can also occur.4

Distinguishing EF and systemic sclerosis is most relevant, because the two can be confused clinically, leading to unnecessary workups. Upon close physical examination, EF patients have normal skin laxity overlying the digits, normal proximal nail folds on capillaroscopy, no sclerodactyly and no history of Raynaud’s.

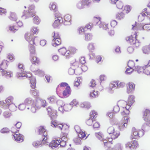

Figures 1 & 2: On exam, the patient had thickening of the skin on her extremities.

Peripheral eosinophilia, although common in EF patients, is not required for diagnosis. Visceral involvement is typically absent in EF; however, rare case reports of pulmonary, renal, cardiac and neurologic involvement exist, the presence of which should lead clinicians to evaluate for other alternative disorders first.2,4

Full-thickness wedge biopsy remains the gold standard of diagnosis. Biopsies that extend deep into the fascia are imperative because superficial biopsies can be consistent with morphea or scleroderma, which can result in misdiagnosis. Eosinophils are not required for histopathologic diagnosis, and clinicopathologic correlation is often required. More recently, MRI has been found to be a useful second-line diagnostic tool in those patients who are not good candidates for wedge biopsy. Findings on MRI include increased signal intensity within the fascia, fascial enhancement after contrast administration, edema and fascial thickening.5

Systemic corticosteroids remain the initial treatment of choice for EF. Many patients require a prolonged treatment course, and no standard therapeutic protocol exists. Initial treatment with prednisone 1 mg/kg/day is typically used and can be tapered over the course of several months, as guided by therapeutic response. Acute symptoms, such as erythema, edema and induration, are generally treatment responsive. However, sclerotic and fibrotic changes can be irreversible. A retrospective study by Lebeaux et al found that initial treatment with three consecutive days of pulse dose intravenous methylprednisolone 0.5–1 mg/g/day prior to oral corticosteroids portended a better prognosis.4 Diagnosis less than six