Image Credit: NotarYES/shutterstock.com

The Case

A 68-year-old woman with a past medical history of Charcot-Marie-Tooth presents with thickening of the skin on her trunk and extremities, which she has had for the past seven months (see Figures 1 and 2). Her symptoms first began with swelling of her bilateral upper and lower extremities. She is now having difficulty with writing and extending her legs. She feels well otherwise and has no other systemic complaints. On exam, she has induration of both forearms and the dorsal aspect of her hands and legs, extending from the feet to above the knees. She has flexion contractures of the fingers and knees (see Figure 3). Exam also reveals hyperpigmented, indurated plaques on the back, abdomen and inguinal folds (see Figure 4). Nailfold capillaroscopy is normal. There is no history of Raynaud’s. Laboratory findings include a normocytic anemia, ANA, Lyme titer and negative serum protein electrophoresis. The remainder of an extensive review of symptoms was unremarkable.

What’s Your Diagnosis?

- Systemic sclerosis

- Hypereosinophilic syndrome

- Lipodermatosclerosis

- Eosinophilic fasciitis

- Acrodermatitis chronica atrophicans

Correct Answer

D. Eosinophilic fasciitis

Eosinophilic fasciitis (EF) is a rare connective tissue disorder characterized by edema and induration of the extremities, and rarely the trunk, that can ultimately result in sclerosis and fibrosis, leading to joint contractures and disability. The cutaneous changes may be accompanied by peripheral eosinophilia, hypergammaglobulinemia, elevated acute-phase reactants and, rarely, underlying malignancy. Diagnosis and treatment can be challenging. Cutaneous clues can prevent misdiagnosis, which can lead to unnecessary tests, invasive workups and delays in treatment.

EF is usually a disease of middle-aged or older adults, but there are reports in children & young adults.

The pathogenesis of EF remains unknown; however, interleukin 5 and matrix metalloproteinase 13 have been postulated to play a role.1 Although strenuous exercise and trauma have been described as eliciting factors for EF, this preceding history tends to be reported in only 30–45% of patients.2 Several medications have been suggested as contributing factors in the development of EF, including statins, phenytoin, subcutaneous heparin and therapies for multiple sclerosis.3 Infectious agents, such as borrelia or mycoplasma, have been described as a possible cause in a minority of cases. Hematologic and myelodysplastic disorders, as well as a few reports of solid tumors, have been associated with EF, and treatment of the underlying disorder can result in resolution of the cutaneous findings.

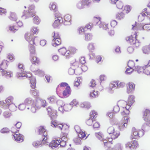

Figure 1.

EF is usually a disease of middle-aged or older adults, but there are reports in children and young adults. It presents with symmetric erythema, swelling and induration of both the upper and lower extremities, which is often accompanied by pain or myalgias. Symptoms can be isolated to the upper or lower extremities, can be unilateral, and can rarely involve the trunk. As the underlying deep sclerosis progresses, patients can develop a depression along the venous channels, called the groove sign, and/or a pseudocellulite appearance of the skin. These findings are especially apparent on exam when the limb is abducted. Sclerosis and fibrosis overlying joints can cause contractures, which are the most common cause of morbidity. Thirty to forty-five percent of patients with EF can have concurrent plaque morphea. Inflammatory arthritis and carpal tunnel syndrome can also occur.4

Distinguishing EF and systemic sclerosis is most relevant, because the two can be confused clinically, leading to unnecessary workups. Upon close physical examination, EF patients have normal skin laxity overlying the digits, normal proximal nail folds on capillaroscopy, no sclerodactyly and no history of Raynaud’s.

Figures 1 & 2: On exam, the patient had thickening of the skin on her extremities.

Peripheral eosinophilia, although common in EF patients, is not required for diagnosis. Visceral involvement is typically absent in EF; however, rare case reports of pulmonary, renal, cardiac and neurologic involvement exist, the presence of which should lead clinicians to evaluate for other alternative disorders first.2,4

Full-thickness wedge biopsy remains the gold standard of diagnosis. Biopsies that extend deep into the fascia are imperative because superficial biopsies can be consistent with morphea or scleroderma, which can result in misdiagnosis. Eosinophils are not required for histopathologic diagnosis, and clinicopathologic correlation is often required. More recently, MRI has been found to be a useful second-line diagnostic tool in those patients who are not good candidates for wedge biopsy. Findings on MRI include increased signal intensity within the fascia, fascial enhancement after contrast administration, edema and fascial thickening.5

Systemic corticosteroids remain the initial treatment of choice for EF. Many patients require a prolonged treatment course, and no standard therapeutic protocol exists. Initial treatment with prednisone 1 mg/kg/day is typically used and can be tapered over the course of several months, as guided by therapeutic response. Acute symptoms, such as erythema, edema and induration, are generally treatment responsive. However, sclerotic and fibrotic changes can be irreversible. A retrospective study by Lebeaux et al found that initial treatment with three consecutive days of pulse dose intravenous methylprednisolone 0.5–1 mg/g/day prior to oral corticosteroids portended a better prognosis.4 Diagnosis less than six

Figure 3. The patient had flexion contractures of her knees.

months from symptom onset was also found to be associated with improved prognosis. A role for immunosuppressive agents in conjunction with corticosteroids has also been discussed in the literature as possibly improving treatment outcomes.2,6 Methotrexate is often the most commonly used corticosteroid-sparing agent; however, the efficacy of mycophenolate mofetil, azathioprine, tumor necrosis factor inhibitors and other therapies has been detailed in small case series. In one retrospective study of 34 patients, methotrexate used in combination with corticosteroids was needed in 44% of patients due to an unsatisfactory response to corticosteroids alone.6

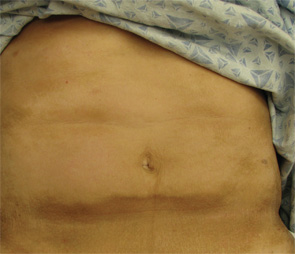

Figure 4. The exam also revealed indurated plaques on the patient’s abdomen.

Because there can be an association with underlying malignancy, most commonly hematologic and myelodysplastic disorders, we advise serum protein electrophoresis and immunofixation testing in all patients. Those patients with cutaneous findings overlying the joints, or those with contractures upon presentation, should receive aggressive physical and/or occupational therapy to prevent morbidity.

Incorrect Answers

A. Systemic sclerosis: Systemic sclerosis and EF can most often be differentiated based solely on clinical exam. The cutaneous findings of systemic sclerosis include sclerosis and skin thickening involving the distal digits; proximal nail fold changes, including erythema and dilated capillaries; and sclerodactyly. Patients classically have Raynaud’s disease. As discussed above, our patient has normal skin laxity overlying the fingers, no proximal nailfold changes and no history of Raynaud’s to suggest systemic sclerosis. In addition, EF patients almost uniformly lack visceral involvement.

B. Hypereosinophilic syndrome: Hypereosinophilic syndrome is characterized by marked peripheral eosinophilia counts (>1,500/microliter) for a period of at least six months without evidence of an alternative etiology. Patients also have symptoms of multiorgan involvement. Fifty percent of patients have cutaneous findings that include urticaria, angioedema and mucosal ulcers, as well as erythematous macules, papules and nodules on the trunk and extremities. Although both entities can have a peripheral eosinophilia, hypereosinophilic patients do not exhibit the cutaneous findings of EF.

C. Lipodermatosclerosis: Lipodermatosclerosis most commonly develops in the setting of long-standing venous insufficiency. Acute symptoms include erythema, tenderness and warmth of the medial ankles. Cutaneous findings later evolve into sclerotic hyperpigmented plaques that resemble an “inverted champagne bottle” on the lower legs. Lipodermatosclerosis may be unilateral or bilateral. The localization of lipodermatosclerosis on the medial lower extremities in the setting of chronic venous insufficiency differentiates this condition from EF. In addition, histopathological examination reveals a lobular panniculitis instead of a deep fasciitis, and laboratory abnormalities are uncommon in lipodermatosclerosis.

E. Acrodermatitis chronica atrophicans (ACA): ACA results from chronic Lyme disease infection, most commonly caused by persistence of Borrelia afzelii in the skin. Months to years after initial infection, patients demonstrate erythema, edema and scaling of the extremities, which can last for years. Later, they develop atrophic, shiny, wrinkled plaques, with prominent vasculature and fibrotic bands that are usually resistant to therapeutic intervention. Although acute ACA can have features that overlap with EF, the end-stage sequelae differ significantly. In addition to physical examination findings, Lyme titers can help differentiate the two entities.

Natalie A. Wright, MD, is the dermatology-rheumatology fellow at Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston. She is a diplomat of the American Board of Dermatology.

Joseph F. Merola, MD, MMSc, FAAD, FACR, is instructor at Harvard Medical School, director of the Center for Skin and Related Musculoskeletal Diseases and director of Clinical Trials at the Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Department of Dermatology and Department of Medicine, Division of Rheumatology.

References

- Asano Y, Hironobu I, Masatoshi J, et al. Serum levels of matrix metalloproteinase-13 in patients with eosinophilic fasciitis. J Dermatol. 2014 Aug;41(8):746–748.

- Lebeaux D, Sene D. Eosinophilic fasciitis (Shulman disease). Best Pract Res Clin Rheumatol. 2012 Aug;26(4):449–458.

- Sheu J, Kattapuram SV, Stankiewicz JM, Merola JF. Eosinophilic fasciitis-like disorder developing in the setting of multiple sclerosis therapy. J Drugs Dermatol. 2014 Sep;13(9):1144–1149.

- Lakhanpal S, Ginsburg WW, Michet CJ, et al. Eosinophilic fasciitis: Clinical spectrum and therapeutic response in 52 cases. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 1988 May;17(4):221–231.

- Eosinophilic fasciitis: Spectrum of MRI findings. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2005 Mar;184(3):975–978.

- Lebeaux D, Frances C, Barete S, et al. Eosinophilic fasciitis (Shulman disease): New insights into the therapeutic management from a series of 34 patients. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2012 Mar;51(3):557–561.