SAN FRANCISCO—A granulomatous vasculitis of the aorta and its branches, giant cell arteritis (GCA) can cause blindness, stroke and aortic aneurysm. GCA is a “frightening” disease, said Cornelia M. Weyand, MD, PhD, professor of medicine, and chief, Division of Immunology and Rheumatology at Stanford University School of Medicine, Stanford, Calif., during her presentation at the California Rheumatology Alliance’s 10th Annual Medical and Scientific Meeting. Using case examples and humorous analogy, Dr. Weyand shared guidance for diagnosing GCA, lessons learned about the inflammatory cascade involved in the disease and implications for treating patients who develop it.

The Right Diagnosis

Presenting symptoms of GCA aortitis can include pulse deficits, fever, a highly elevated sedimentation rate, aneurysm or aortic dissection. GCA can co-occur with polymyalgia rheumatica. Age older than 50 years is a predominant risk factor, said Dr. Weyand, and can help clinicians differentiate patients with GCA from those with Takayasu’s arteritis (TA), which occurs almost exclusively in patients younger than 40 years. In addition, TA almost always affects the carotid arteries and the proximal parts of the subclavian arteries, and frequently is seen in abdominal branches of the aorta; GCA has a preference for the distal subclavian and axillary arteries.

Radiology colleagues can be powerful allies during the diagnostic process. “CT angiography,” Dr. Weyand asserted, “gives us fast and very reliable data on whether patients have large vessel involvement. You need to work with your radiologist to be sure you look not only at the core of the aorta and the large vessels, but also into the periphery.” PET scans, she added, “are not as sensitive as we hoped they would be, particularly in patients that are on treatment.” There may be advances with new combined PET/MRI technology (Note: In January, Stanford installed the world’s first fully integrated PET/MRI scanner), but that has yet to be demonstrated.

Compared with men, women are at greater risk for pain undertreatment. “Maybe it’s because women exprThere is no evidence right now that if you were to stop the disease entirely that the prognosis of our patients would improve.

What Goes Wrong?

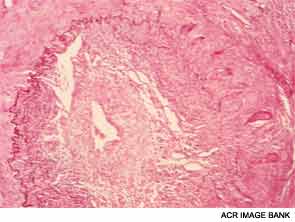

Dr. Weyand shared lessons learned from her research into the mechanisms of inflammatory blood vessel disease conducted with colleagues at both Stanford University and the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minn. In GCA, vascular inflammation results from a domino effect of activated cytokines, producing a sort of “cytokine soup.” Macrophages cohere to form granulomas, often within the medial layer of the aorta. The site of entrance for the inflammatory cells is the adventitia in the outer lining of the aorta, she pointed out. Analysis of cell lesions has demonstrated a complex makeup of two different T-cell populations in addition to three different dendritic cell populations. As opposed to atherosclerosis, in which lesions form in the interior of the blood vessel, in GCA the disease process starts “at the back door.”