ATLANTA—A 7-year-old girl presented to her pediatrician with a fever, nausea, vomiting and a headache, and was diagnosed with a sinus infection. As her symptoms grew worse and more complex, the case led neurologists and rheumatologists on a long hunt for a diagnosis—ultimately, anti-myelin oligodendrocyte glycoprotein (anti-MOG) autoimmune encephalomyelitis—that highlighted how patience, a thorough workup and multi-department teamwork can be crucial for proper diagnosis and management of a pediatric patient with inflammatory brain disease.

ATLANTA—A 7-year-old girl presented to her pediatrician with a fever, nausea, vomiting and a headache, and was diagnosed with a sinus infection. As her symptoms grew worse and more complex, the case led neurologists and rheumatologists on a long hunt for a diagnosis—ultimately, anti-myelin oligodendrocyte glycoprotein (anti-MOG) autoimmune encephalomyelitis—that highlighted how patience, a thorough workup and multi-department teamwork can be crucial for proper diagnosis and management of a pediatric patient with inflammatory brain disease.

A discussion of the case and its lessons was led at the 2019 ACR/ARP Annual Meeting by Elizabeth Wells, MD, director of inpatient neurology at Children’s National Hospital, Washington, D.C., and Heather Van Mater, MD, MSc, a pediatric rheumatologist at Duke Children’s Hospital, Durham, N.C.

Initial Diagnosis

After the sinus infection diagnosis, the girl’s headache got worse and she had difficulty using her hand, prompting an emergency department visit. She was found to have sinusitis on a computerized tomography scan, with a white blood count (WBC) of 12.5 and a C-reactive protein (CRP) level of 1.6. With a severe headache, a moody disposition and sleepiness at Day 12, she was referred to neurology.

“The biggest things for me as a neurologist at this point would be that focal complaint—that her right hand was not working at some point—as well as the fact that the headache is severe, persistent and not getting better—and that it was her first headache,” with no history of headache or migraine, Dr. Wells said.

A magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scan showed sphenoid sinusitis with T2 changes in the frontal lobe. Because of the migraine, she was given prednisone for five days on day 17. Her symptoms resolved, but after the steroids were stopped she again developed a headache and a low-grade fever, with excessive sleepiness and irritability.

She was admitted to the hospital on the 25th day, still with a presumed migraine. She had a CRP of 11.7, WBC of 34.9 and hemoglobin of 12.9. She was treated for migraine, released with an oral steroid taper and improved at home.

Signs of a Deeper Problem Missed

Dr. Wells said signs of a deeper problem were missed early on.

“There may have been some anchoring bias here, where she got diagnosed with migraine and then was getting better, but I still think back to those focal symptoms she had initially,” as well as her abnormal lab findings, Dr. Wells said.

A few days later, things got much worse. The girl had hallucinations and a seizure that became status epilepticus, with a WBC of 34.8, an erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) of 36 and a CRP of 11.2. A lumbar puncture found a WBC of 211 with a segmented neutrophil reading of 81% and red blood cell count of zero.

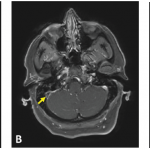

On MRI, she was found to have cortical restriction with increased T2 signaling of the left temporal lobe, left insula and left frontal lobe.

Doctors were now concerned about autoimmune encephalitis or infection, and she was transferred because the community hospital where she was had no infectious disease or rheumatology department. At the new center, the girl was agitated, was asking that music be turned off when none was playing, and she didn’t recognize her parents.

Another MRI found progressive disease that was bilateral, but worse on the left, with leptomeningeal enhancement in the wake of seizures.

Possible Autoimmune Encephalitis

Criteria for possible autoimmune encephalitis (AE) are rapid progression of working memory deficits in less than three months, altered mental status or psychiatric symptoms, one or more of new focal central nervous system findings, seizures unexplained by a previous disorder, a white blood cell count of more than 5 cells per cubic millimeter, MRI features suggesting encephalitis, and “reasonable exclusion of alternative causes,” which Dr. Wells called, “the tricky part.”1

Meeting these criteria is “not a diagnosis in and of itself,” but is only a guide signaling the clinician to “think about autoimmune encephalitis,” Dr. Van Mater said.

For definite autoimmune encephalitis, the history, exam and labs all need to be consistent with AE, with no other clear diagnosis, and a positive anti-neuronal antibody; a patient has probable AE when his or her history, exam and labs are all consistent with AE, with no other clear diagnosis, but is negative for an anti-neuronal antibody.

Anti-NMDA-Receptor Encephalitis

A diagnosis of anti-N-methyl D-aspartate (NMDA) receptor encephalitis requires meeting these three criteria: 1) Onset in less than three months of four of these six symptoms: abnormal behavior or cognitive dysfunction, speech dysfunction, seizures, a movement disorder or dyskinesia, a decreased level of consciousness and autonomic dysfunction, or central hypoventilation; 2) an abnormal electroencephalogram and/or abnormal cerebrospinal fluid pleocytosis or oligoclonal bands; and 3) reasonable exclusion of other disorders.

Diagnosing autoimmune brain disease can be challenging because patients’ phenotypes overlap, Dr. Van Mater said.2

“There’s such overlap in their ultimate diagnosis based on phenotype alone that you have to do a pretty broad evaluation to make the diagnosis,” she said.

After a positive anti-nuclear antibody test and an extensive infectious disease workup that was negative, clinicians continued to ponder the diagnosis, with at least some factors both supporting and running counter to diagnoses of primary central nervous system (CNS) vasculitis, autoimmune encephalitis, systemic rheumatic disease, demyelinating disease, para-infectious and active bacterial infection.

An angiogram was unrevealing. NMDA and other anti-neuronal antibody testing was also negative.

The girl was close to meeting the criteria for autoantibody-negative but probable autoimmune encephalitis, but the “exclusion of alternative diagnoses” requirement “gives us pause,” Dr. Van Mater said. Clinicians remained concerned about a post-infectious component being involved, as well as about potential angiographically silent CNS vasculitis.

The patient was discharged from the hospital with this diagnostic cloud of doubt lingering. She was given anti-seizure medication with the plan to follow up in one week to determine intravenous immunoglobulin (IVIG) and steroid frequency based on how she did. But in just three days, she had new onset of acute vision loss in her left eye. An MRI found an inflamed left optic nerve.

“This brings us into the demyelinating camp because it’s an optic neuritis,” Dr. Wells said.

Anti-MOG Autoimmune Encephalomyelitis

Clinicians began to suspect anti-MOG autoimmune encephalomyelitis and Dr. Van Mater called an expert in Australia, who confirmed that neuroretinitis was not uncommon in the disease. The MOG test came back high titer positive.

The MOG test has been commercially available for two years, and the disease is now being found in 18–35% of children with a first acute demyelinating episode. It is associated with a whole spectrum of demyelinating disease, Dr. Wells said.3

“When patients with MOG encephalitis have had brain biopsies, they are found to have lymphocytic perivascular infiltration in many cases,” Dr. Van Mater said. “And it’s now thought that many of the kids we previously diagnosed with [angiographically silent] CNS vasculitis—who didn’t have classic vasculitis on their biopsy but more of this perivascular lymphocytic infiltrate—were likely MOG positive.”

Treatment

The treatment is similar to that of autoimmune encephalitis treatment, the doctors said. Most pediatricians will treat AE with rituximab, and for adults the tendency is to treat with rituximab plus cyclophosphamide.

When treating autoimmune brain disease, they said, remember that not everyone needs the same treatment. Consider bridge therapy with steroids and IVIG when adding a disease-modifying anti-rheumatic drug, and consider spacing medications out rather than stopping suddenly. Also, they said, with aggressive subtypes, treat with rituximab early, and consider treating for a longer period of time and following CD19 and 20 cell counts to guide rituximab redosing.

The girl was treated with rituximab, intravenous steroids and IVIG. She has continued on the antiseizure medication because weaning gave rise to more seizures. Her vision has improved, but she had a mild flare with vision changes when IVIG was slowed. Clinicians added mycophenolate mofetil and continued every-six-month rituximab. Since being off steroids and IVIG for seven months, she’s had no flares, though her MOG remains positive two years later.

“There are many different models for how we treat autoimmune or autoinflammatory brain disease—care has to be multi-disciplinary. Many of us now have multidisciplinary clinics where we’re actually seeing the patients together, discussing them in real time with rheumatology, neurology, psychiatry and neuropsychology, speech and physical medicine,” Dr. Wells said. “Keeping in mind that multi-disciplinary approach really serves these patients.”

Thomas R. Collins is a freelance writer living in South Florida.

References

- Graus F, Titulaer MJ, Balu R, et al. A clinical approach to diagnosis of autoimmune encephalitis. Lancet Neurol. 2016 Apr;15(4):391–404.

- Cellucci T, Tyrrell PN, Twilt M, et al. Distinct phenotype clusters in childhood inflammatory brain diseases: Implications for diagnostic evaluation. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2014 Mar;66(3):750–756.

- Papathanasiou A, Tanasescu R, Davis J, et al. MOG-IgG-associated demyelination: Focus on atypical features, brain histopathology and concomitant autoimmunity. J Neurol. 2019 Oct 22. [Epub ahead of print]