An activated macrophage.

David Scharf/Science Source

Primary hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis (HLH) is caused by genetic mutations and inherited syndromes; it therefore occurs in the pediatric age group. Secondary HLH, however, is more common in adults and is often triggered by other disease states, such as malignancies, chronic immunosuppression, infections and autoimmune disease.1,2 Macrophage activation syndrome (MAS) is a subset of secondary HLH seen in patients with autoimmune diseases, such as systemic juvenile idiopathic arthritis (sJIA), systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) and adult-onset Still’s disease.3

A high index of suspicion for HLH is crucial because treatment delay is associated with high mortality and morbidity. Excluding other causes of the symptoms also prevents inappropriate treatment, which can lead to poor outcomes.

Case Presentation

A 69-year-old woman was admitted with a one-week history of fever. She reported at least two temperature spikes daily, which were associated with chills but not rigors.

She noted two to three days of nausea, decreased appetite, pharyngitis, frontal headaches and arthralgias that migrated between her neck, shoulders, ankles and knees. She also had a cough, productive of clear phlegm and associated with exertional shortness of breath.

The patient had a 14-year history of anti-neutrophil cytoplasmic antibody (ANCA) associated vasculitis (AAV). She had presented with glomerulonephritis, which was treated with cyclophosphamide and glucocorticoids, followed by azathioprine. She reported that her current complaints were similar to the symptoms she experienced when she was first diagnosed with AAV.

| LAB VALUE | Day 1 | Day 2 |

|---|---|---|

| Sodium (135–145 mmol/L) | 129 mmol/L (L) | 132 mmol/L (L) |

| Carbon dioxide (21–32 mmol/L) | 22 mmol/L | 22 mmol/L |

| BUN (7–18 mg/dL) | 22 mg/dL(H) | 24 mg/dL (H) |

| Creatinine (0.60–1.30 mg/dL) | 1.60 mg/dL(H) | 1.7 mg/dL (H) |

| Lactic acid (0.36–1.7 mmol/L) | 1.64 mmol/L | |

| AST (15–37 U/L) | 522 U/L (H) | 717 U/L (H) |

| ALT (13–61 U/L) | 228 U/L (H) | 292 U/L (H) |

| Alk Phosphatase (45–117 U/L) | 168 U/L (H) | 163 U/L (H) |

| Albumin (3.4–5.0 mg/dL) | 2.8 mg/dL (H) | 2.6 mg/dL (L) |

| WBC (4.5–10.5 10*3/uL) | 3.96 K/uL (L) | 3.92 K/uL( L) |

| Band neuts % (2–8%) | 0.03 | 14% (H) |

| Hgb (11.4–15.5 g/dL) | 11.6 g/dL (L) | 10.9 g/dL (L) |

| Hct (37.0–47.0%) | 32.2% L | 31.0% L |

| Platelet count (130–385 10*3/uL) | 38 K/uL (L) | 36 K/uL (L) |

| ESR (0–20 mm/HR) | 22 mm/HR (H) | |

| CRP (<0.300 mg/dL) | 18.1mg/dL (H) | |

| Total creatinine kinase (21-215 U/L) | 156 U/L | |

| LDH (84–246 U/L) | 1,275 U/L (H) | |

| Monoscreen | Negative | |

| Influenza Type A and B Ag | Negative | |

| Hepatitis panel (Hepatitis A IgM, HBsAg, Hep B Core IgM, Hepatitis C Ab | Negative | |

| HIV 1&2 Antibody | Negative | |

| HIV p24 Antigen | Negative |

Her home medication use included azathioprine 100 mg daily, amlodipine 5 mg daily and 25 mg of metoprolol twice daily.

At the time of presentation, her temperature was 102.6° F, and she had a blood pressure of 83/63 mmHg and a heart rate of 102/minute. Her respiratory rate was 19 breaths/minute with oxygen saturation of 93% on room air.

She was oriented, but appeared uncomfortable. Her mucosal membranes were dry, and she was tachycardiac; her examination was otherwise not revealing.

Her laboratory tests were consistent with shock (see Table 1, left). A computerized tomography (CT) scan of her chest demonstrated small pleural effusions with bibasilar infiltrates, but no lymphadenopathy. An abdominal ultrasound confirmed her liver was grossly unremarkable, with no dilatation of the common bile duct, no gall stones, ascites or splenic enlargement.

Diagnosis & treatment: Her admitting diagnosis was septic shock, and she was treated with intravenous vancomycin and cefepime. An infectious disease specialist was consulted to evaluate the patient for atypical infections. The patient’s blood and urine cultures did not identify an organism, so she was transitioned to azithromycin.

During her admission, she had a persistent, high-grade fever, with a maximum temperature of 103.6° F. Her respiratory status continued to worsen, with tachypnea and hypoxia requiring increasing oxygen supplementation. Her laboratory test demonstrated leukopenia, bandemia, thrombocytopenia, transaminasemia and declining renal function. She was noted to have a discordance between her erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) and C-reactive protein (CRP), and tests for infectious etiologies, including viral hepatitis, human immunodeficiency virus and parvovirus were all negative.

She was treated empirically with 500 mg of intravenous methylprednisolone to address the possibility that she was experiencing a relapse of her underlying rheumatic disease, and she was transferred to our center for rheumatology input.

Upon arrival, she was noted to have a persistent fever and respiratory distress; she was tachypneic and was using accessory muscles despite high-flow oxygen therapy. She was subsequently intubated for respiratory failure.

A repeat chest X-ray showed worsening bilateral pulmonary infiltrates, and she was restarted on vancomycin, cefepime and doxycycline. She was also given pulse-dose methylprednisolone 1 gm daily for three days.

Further laboratory testing (see Table 2, below) again showed discordance between her ESR and CRP, prompting the consideration of alternative diagnoses to sepsis and vasculitis. Bronchoalveolar lavage failed to demonstrate evidence of diffuse alveolar hemorrhage (DAH), infection or malignancy. She subsequently developed altered mental status, which was not felt to be due to infection or non-convulsive status epilepticus.

| LAB COMPONENT | day 3 |

|---|---|

| Sodium (135–145 MMol/L) | 139 MMol/L |

| BUN (6–20 mg/dL) | 31 mg/dL (H ) |

| Creatinine (0.5–1.2 mg/dL) | 1.99 mg/dL (H) |

| AST (10–42 IU/L) | 626 IU/L (H) |

| ALT (10–60 IU/L) | 245 IU/L (H) |

| ALP (42–121 IU/L) | 175 IU/L (H) |

| WBC (4.0–10.5 K/uL) | 4.6 K/uL |

| Hemoglobin (12.0–16.0 g/dL ) | 11.5 g/dL (L) |

| Hematocrit (36–46%) | 31.7% (L) |

| Platelets (130–400 K/uL) | 50,000 K/uL (L) |

| ESR (0–30 mm/HR) | 5 mm/HR |

| CRP (<1.0 mg/dL) | 14.9 mg/dL (H) |

| LDH (135–214 IU/L) | 2010 IU/L (H) |

| Ferritin (13–150 ng/mL) | 54,059 ng/mL (H) |

| Triglycerides (<150 mg/dL) | 638 mg/dL (H) |

| Fibrinogen (204–475 mg/dL) | 199 mg/dL (L) |

| ANCA screen (C-ANCA and P-ANCA titer) | Negative |

| Rheumatoid factor | <14 IU/mL |

| Ribosomal protein | <1.0 NEG AI |

| Anti-DNA, native double strand | <1 IU/mL |

| Sm/RNP | <1.0 NEG AI |

| Scleroderma (SCL-70) | <1.0 NEG AI |

| Sjögren’s antibody SSA | <1.0 NEG AI |

| Sjögren’s antibody SSB | <1.0 NEG AI |

| Anti-Smith antibody | <1.0 NEG AI |

| Anti-centromere B antibody | <1.0 NEG AI |

| Anti Jo-1 antibody | <1.0 NEG AI |

| Anti-Streptolysin O | <50 Ref: <200 IU/mL |

| Anti-nuclear antibody | Negative |

| CCP Ab IgG | 77 H, Ref: strong positive >59 |

| Complement C3 | 70 L, Ref: 90–180 mg/dL |

| Complement C4 | 32.8, Ref: 10–40 mg/dL |

| Thyroid peroxidase (TPO) Ab | <1, Ref: <9 IU/mL |

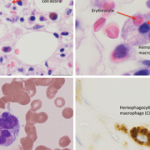

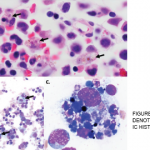

A bone marrow biopsy was obtained and demonstrated a clonal T cell population, with megakaryocytic hyperplasia and rare hemophagocytosis (see Figure 1, opposite). Serum soluble interleukin (IL) 2 receptor (IL-2R) levels were elevated at 10,219 pg/mL (reference range 532–1,891 pg/mL).

A diagnosis of HLH was made, and the antibiotics were stopped. The patient was subsequently treated with 112.5 mg/m2 etoposide (corrected based on renal function) twice weekly for two weeks and 20 mg of intravenous dexamethasone daily for two weeks, after which she gradually improved. She was subsequently extubated, with improvement in mental status, although she still has some memory issues.

She was eventually discharged to a subacute facility for inpatient rehabilitation, where she received 112.5 mg/m2 etoposide weekly for three weeks and 150 mg/m2 of etoposide (corrected based on renal function) weekly for three weeks. She also received dexamethasone, which was tapered from 10 mg daily for two weeks to 5 mg daily for two weeks to 2.5 mg daily for two weeks to 1.25 mg daily for one week, before being discontinued.