A 56-year-old African American man presents to the emergency department with polyarthralgias and a fever of 103ºF. One month prior to admission, he presented with right knee pain and swelling. Blood cultures grew S. epidermidis. He was treated for presumed septic arthritis complicated by MSSE bacteremia. He was treated with meropenem and a prolonged course of daptomycin following discharge.

On the current presentation, the patient complained of fever of two days’ duration as well as left elbow and bilateral hand, knee and foot pain. He denied sick contacts, weight loss, night sweats, hemoptysis, abdominal pain, chest pain or dyspnea. His past medical history was significant for rheumatoid arthritis (RA), managed on abatacept. He had a dilated cardiomyopathy, treated with a left ventricular assist device (LVAD); atrial fibrillation, for which he was maintained on anticoagulation; a history of chronic alcohol use; and chronic kidney disease stage 2.

On physical examination, vital signs included a temperature of 103ºF, blood pressure of 122/90, heart rate of 122 beats per minute, respiratory rate of 20–33 breaths per minute and oxygen saturation of 99%. He weighed 109 kg and appeared in no acute distress, with normal mental status. Cardiopulmonary exam demonstrated normal S1 and S2, no murmurs, rubs or gallops, clear breath sounds and symmetric chest expansion. No rashes, ulcerations, lesions or nodules were noted. There was no hepatosplenomegaly or abdominal tenderness. Musculoskeletal exam revealed warmth, erythema, tenderness, swelling and limited range of motion of both hands (dorsum, right third proximal interphalangeal joint, right first interphalangeal joint and left wrist), as well as both elbows, ankles, metatarsal joints and the right knee.

Question 1

Based on the above findings and medical history, which of the following is the most likely cause of these symptoms?*

a. septic arthritis

b. rheumatoid arthritis

c. crystal arthropathy

d. osteoarthritis

e. reactive arthritis

Given the constellation of symptoms and risk factors, there is initial concern for septic arthritis, as well as an RA flare. The patient was admitted to the critical care unit, given his cardiac history, and started on broad-spectrum antibiotics, given his recent hospitalization for bacteremia.

Chad Zuber/shutterstock.com

Labs upon admission were significant for mild leukocytosis of 12,800, lactic acid of 1.3 mg/dL, C-reactive protein of 329 mg/L with sedimentation rate >100 mm/hr, procalcitonin of 2.0 ng/mL and a serum uric acid of 6.0 mg/dL. Emergent aspiration of the right knee produced purulent fluid with a white blood count of 117,000 with a differential of 92% polys. It was at that point that septic arthritis immediately became the primary diagnosis.

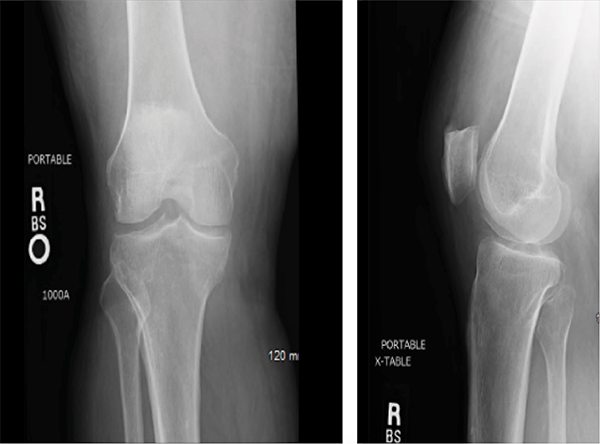

Blood cultures remained negative, and transesophageal echocardiogram (TEE) did not show any valvular vegetations. During the hospitalization, the patient’s pain worsened to the point where he was unable to move his right leg and left wrist, despite antibiotic therapy. Knee and ankle X-rays did not show erosions, bony changes, fractures or soft tissue inflammation (see Figures 1–4).

Although plain radiographs play a minor a role in the diagnosis of septic arthritis, their ease and low cost make X-rays useful tools. The earliest changes seen with septic arthritis include soft tissue swelling, and joint space widening or narrowing. Evidence of superimposed osteomyelitis can be seen in the form of periosteal bone reaction and bone destruction.1 Erosions are a feature common to infectious, as well as inflammatory, joints in the setting of both gout and rheumatoid arthritis.

Next, the patient underwent arthroscopic lavage of the left elbow, which showed 30,000 cells with 82% neutrophils, negative cultures, 154,000 red blood cells and positive intracellular monosodium urate crystals.

Left wrist and right knee synovial biopsies revealed mild to moderate acute inflammatory changes consistent with gouty arthritis. No crystals were visualized, possibly due to specimen fixation in formalin solution. Antibiotic therapy was continued despite the lack of positive cultures, and colchicine was started for polyarticular gout. Corticosteroids were not given because of persistent fevers and concern for systemic infection.

The patient’s leukocytosis and inflammatory markers improved, and the patient was eventually discharged after 40 days of hospitalization.

Question 2

Which of the following is the most commonly used treatment modality for acute gout?

a. antibiotics

b. corticosteroids

c. acetaminophen

d. infliximab

e. anakinra

Gout is the most common form of inflammatory arthritis, with a prevalence of 5% in the U.S., and is characterized by swollen, erythematous and tender joint(s). Risk factors include alcohol use, obesity, kidney disease and any disease causing high cellular turnover, such as malignancy.

Depending on the clinical situation, acute attacks are generally treated with corticosteroids, colchicine or non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs). Recurrent attacks can be prevented with colchicine, NSAIDs, urate-lowering agents, such as xanthine oxidase inhibitors (allopurinol or febuxostat) or uricase, or by increasing secretion in a functioning kidney with probenecid or sulfinpyrazone. Urate-lowering agents are indicated in patients with tophaceous gout, frequent attacks despite prophylactic colchicine or NSAID use, urolithiasis and multiple comorbidities.2 When primary measures are ineffective or contraindicated, therapies targeted at cytokines IL-1, such as anakinra, can help treat gouty attacks.

In addition, patients need to adhere to a dietary regimen and a healthy lifestyle to help prevent further attacks.

Our patient was maintained on colchicine 0.6 mg three times a day and discharged on febuxostat, after which outpatient uric acid levels decreased to normal levels for the first time in four years.

The earliest changes that can be seen in a patient with septic joints include soft tissue swelling & joint space widening or narrowing. Evidence of superimposed osteomyelitis can be seen in the form of periosteal bone reaction & bone destruction.1

Question 3

What is (are) the most common outcome(s) of untreated gout? (Multiple choices may be correct.)

a. sepsis

b. urolithiasis

c. permanent joint destruction

d. bacteremia

e. tophi

Gout is an inflammatory disorder in which uric acid, a toxic metabolic product, accumulates in the form of crystals in the joint spaces. Unabated accumulation of urate can result in tophi that present as papules or nodules in various locations, including tendons, cartilage, osteoarthritis nodes and bursae. The presence of tophi increases the risk of developing joint deformities and secondary osteoarthritis. Following injury, these tophi can become acutely inflamed and even erupt through the skin.

Approximately 20% of patients with chronic gout will develop nephrolithiasis due to both uric acid formation and calcium oxalate deposition.2 This may lead to obstructive nephropathy and subsequent infection.

Figures 1 & 2: X-rays of the Right Knee

Question 4

Which of the following can be used to aid in the diagnosis of gout? (Multiple answer choices may be correct.)

a. synovial fluid analysis

b. demonstration of fever and joint pains

c. clinical evidence of gout

d. imaging evidence of urate deposition

e. all of the above

In 2015, the ACR released new criteria for the classification of gout.3 These criteria emphasize physical exam and medical history, with less focus on laboratory results or invasive diagnostic techniques, such as synovial fluid analysis; the sensitivity of joint aspiration can be low, based on the size of the joint space, as well as the experience of the person obtaining and/or examining the sample.

These criteria utilize a point system in which different symptoms and signs are taken into account: distribution of joint involvement, presence of pain and/or erythema, time course of symptomatic episode, clinical evidence of tophi, serum urate levels, synovial fluid analysis, imaging evidence of urate deposition and/or joint damage. Negative points are given for serum urate levels <4 mg/dL and negative synovial findings. A Web-based calculator can be accessed through the ACR’s website.

Question 5

Is it typical to have gout in a patient with known seropositive RA?

a. Yes, with a prevalence greater than that of the general population

b. No, with a prevalence less than that of the general population

c. No, with a prevalence equal to that of the general population

Gout can occur in patients with RA, but at a lower prevalence than that of the general population (2.4% vs. 5.2% over 25 years).4 Given the increased risk of joint destruction and clinical overlap, it is important to confirm the diagnosis of gout. Uncontrolled obesity, alcohol use and kidney disease increase the risk of developing gout.

This patient was diagnosed with RA five years prior to admission on the basis of scleritis in the setting of a positive rheumatoid factor and cyclic citrullinated peptide. Because the patient was transitioning care, many past diagnoses remained fixed in his medical history. The patient had been diagnosed with gout many years earlier; however, he was never placed on a consistent uricosuric regimen and was actively treated only for RA.

After failing therapy with methotrexate, hydroxychloroquine, infliximab and tocilizumab, based on persistent symptoms and side effects, the patient was placed on abatacept as a long-term treatment regimen. His primary presentation on admission heightened concern for infection in the setting of active immune suppression.

Despite adjusting medications, in a five-year span, the patient had 15 clinical visits in which he described either mono- or polyarthritis. His persistent joint stiffness and limited range of motion in some joints despite treatment with abatacept led his clinicians to consider gout.

There are several documented instances in which this patient continued to demonstrate worsening arthralgia, despite medical therapy for RA. For example, he presented with synovitis of his right proximal interphalangeal joint and an elbow bursitis (CDAI score of 33). He was treated with prednisone for a presumed RA flare despite continued therapy on abatacept. Over the course of several months, his ongoing joint pain, which was refractory to abatacept and steroids, was considered to be due to his RA. A more diligent review of his persistent joint pain led to the diagnosis of gout.

In October 2015, the patient was to have left ankle surgery for erosive RA. In that time, the patient continued to complain of swelling in fingers and left wrist without significant improvement on his medications. Shortly after, the patient was admitted to the hospital as mentioned above.

Figures 3 & 4: X-rays of the Left Wrist

Question 6

Is anchoring bias more prevalent in patients with many co-morbidities?

a. yes

b. no

c. unknown but likely

Anchoring bias fits the general umbrella of diagnostic errors. Diagnostic errors include diagnoses that were missed, incorrect or delayed.5 Unfortunately, these errors are not usually detected until patients suffer worsening consequences of their disease process, which include hospitalization or even death. Efforts have been made to identify errors by pinpointing possible trigger events. The limitations of managing complex patients in the outpatient setting heighten the risk of suffering a diagnostic oversight.

Question 7

What are ways physicians can help target when a previous diagnostic error has been made? (Multiple answer choices may be correct.)

a. review medications

b. identify unusual patterns of care

c. identify frequent hospitalizations and/or ED visits

d. review most common malpractice claims

e. utilize more laboratory and invasive techniques

Many studies have been performed to help identify and address diagnostic errors in routine outpatient practice. Most errors involve the breakdown of processes related to the patient–practitioner clinical encounter.6 Thus, it is important to prevent medical error by ensuring proper classification of symptoms and, therefore, diagnoses. By reviewing medications and identifying unusual patterns of care, such as frequent physician visits and/or hospitalizations, physicians can start to analyze diagnostic or medical errors.

The question can be asked, “At what point should one begin to consider alternative diagnoses if multiple treatment modalities have failed?”

In this case, the patient’s comorbidities made it especially difficult to manage medications because, although he was treated with several disease-modifying anti-rheumatic agents, some therapeutic failures were attributed to his underlying multi-organ disease. Methotrexate was stopped secondary to elevated liver enzymes from chronic alcohol use, hydroxychloroquine stopped secondary to worsening uveitis, tocilizumab stopped in the context of neutropenia and infliximab stopped in the setting of congestive heart failure.

It is important to keep the list of differential diagnoses broad and to limit anchoring bias.

Discussion

Gout affects multiple organ systems, most commonly joints but also skin, soft tissue and kidneys.7 In this case, the patient, who had a known diagnosis of RA, presented with arthritis and fevers; however, secondary to confounding comorbidities, it was only after undergoing multiple, highly invasive procedures and a prolonged hospital course that a diagnosis of gouty arthritis was made.

Gout is the most common form of inflammatory arthritis with a prevalence of 5% in the U.S., and is characterized by swollen, erythematous & tender joint(s).

This case highlights the prevalence of anchoring bias in medicine and the pitfalls that prevent us from formulating thorough differentials. This exercise expands on the concept of premature closure or the failure to consider alternative diagnoses after an initial impression is formed.8 In anchoring bias, there may be a continued fixation over the initial diagnostic impression in the face of other compelling data.

An estimated 75,000 hospitalizations per year are due to preventable adverse events that occur in outpatient settings in the U.S.9 Errors occur most frequently in the testing phase (e.g., failure to order, report and follow up laboratory results; 44%), clinician assessment errors (failure to consider and overweighing competing diagnosis; 32%), inadequate history taking (10%), incomplete physical examination findings (10%), and referral or consultation errors and delays (3%).10

Although diagnostic errors can lead to disastrous consequences, efforts have been made to identify points along the medical care process that can be monitored more thoroughly. Healthcare professionals can work together to make sure that tests are ordered correctly and followed up appropriately.

Sneha N. Patel, MD, is currently an internal medicine resident at Drexel University College of Medicine/Hahnemann University Hospital in Philadelphia. She completed her Bachelor of Science from Boston University in 2011 and received her Medical Degree from St. George’s University in 2015. Her research interest is in rheumatologic disorders.

Sneha N. Patel, MD, is currently an internal medicine resident at Drexel University College of Medicine/Hahnemann University Hospital in Philadelphia. She completed her Bachelor of Science from Boston University in 2011 and received her Medical Degree from St. George’s University in 2015. Her research interest is in rheumatologic disorders.

Monica V. Mohile, MD, is the chief rheumatology fellow at Drexel University College of Medicine/Hahnemann University Hospital. She completed her internal medicine residency at the University of Pittsburgh Medical Center. She attended medical school at Northeast Ohio Medical University. Her research areas of interest include systemic lupus erythematous.

Monica V. Mohile, MD, is the chief rheumatology fellow at Drexel University College of Medicine/Hahnemann University Hospital. She completed her internal medicine residency at the University of Pittsburgh Medical Center. She attended medical school at Northeast Ohio Medical University. Her research areas of interest include systemic lupus erythematous.

Arundathi Jayatilleke, MD, is the program director of the Drexel Rheumatology Fellowship at Drexel University. She completed her Bachelor of Science and Master of Science Degrees at Yale University and received her medical degree from Duke University in 2015. Dr. Jayatellike completed her internal medicine residency at New York Presbyterian Hospital and her rheumatology fellowship at the Hospital for Special Surgery. Her research interest is in inflammatory arthritis.

Arundathi Jayatilleke, MD, is the program director of the Drexel Rheumatology Fellowship at Drexel University. She completed her Bachelor of Science and Master of Science Degrees at Yale University and received her medical degree from Duke University in 2015. Dr. Jayatellike completed her internal medicine residency at New York Presbyterian Hospital and her rheumatology fellowship at the Hospital for Special Surgery. Her research interest is in inflammatory arthritis.

Answer Key

- C

- B

- C, E

- E

- B

- C

- A, B, C

References

- Nunez-Atahualpa L. Septic arthritis imaging. Medscape. 2016 May 12.

- Ryan LM. Gout. Merck Manual, professional edition.

- Neogi T, Jansen TL, Dalbeth N, et al. Gout classification criteria. An American College of Rheumatology/European League Against Rheumatism collaborative initiative. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2015 Oct;67(10):2557–2568.

- Jebakumar AJ, Udayakumar PD, Crowson CS, Matteson EL. Occurrence of gout in rheumatoid arthritis: It does happen! A population-based study. Int J Clin Rheumtol. 2013 Aug;8(4):433–437.

- About Diagnostic Error. Society to Improve Diagnosis in Medicine. 2016.

- Singh H, Giardina TD, Meyer AN, et al. Types and origins of diagnostic errors in primary care settings. JAMA Intern Med. 2013 Mar 25;173(6):418–425.

- Eggebeen AT. Gout: An update. Am Fam Physician. 2007 Sep 15;76(6):801–808.

- Anchoring bias with critical implications. AORN J. 2016 Jun;103(6):658–631.

- Woods DM, Thomas EJ, Holl JL, et al. Ambulatory care adverse events and preventable adverse events leading to a hospital admission. Qual Saf Health Care. 2007 Apr;16(2):127–131.

- Schiff GD. Diagnostic error in medicine. Analysis of 583 physician-reported errors. Arch Intern Med. 2009 Nov 9;169(20):1881–1887.