“Fine,” she said, suddenly standing.

“And,” I flipped the page on her clinic notes back to the original consult, “you’ve lost 12 lbs. since mid-March. I’m arranging for an abdominal/pelvic CT scan.”

Mrs. N sat back down. Her face was flushed. I placed the thermometer back in her mouth, 102.4ºF. “I … I don’t feel well. It’s one of those spells.” Joanne came in, and we laid Mrs. N down on the exam table and placed a damp cloth on her forehead.

“Let me call Larry. I want to admit you,” I decided.

Hospital Admission

The admission was frustratingly inconclusive. On Day 1, after blood and urine cultures were obtained, IV antibiotics were started on the recommendation of the infectious disease (ID) consultant. Again, nothing grew out. A skin test for exposure to tuberculosis was negative. A slew of laboratory studies was drawn. Tests for everything from Q fever to relapsing fever, Brucellosis, Lyme disease, HIV, ehrlichiosis, histoplasmosis, toxoplasmosis, cytomegalovirus, herpes and hepatitis B and C, were dutifully ordered and drifted back with monotonous normalcy. I asked pathology to comment on her peripheral smear; a basic test in which a sample of blood is smeared on a slide and the pathologist evaluates the sample for evidence of leukemia or parasitic infections. This was unremarkable.

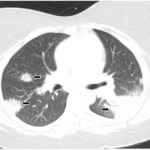

Needless to say, the other studies, the CT scan of the abdomen and pelvis, the colonoscopy, the pelvic exam, a repeat echocardiogram, were non-diagnostic. On Day 4, with daily fevers continuing to spike, ID recommended that I discontinue the antibiotics. Hematology reviewed the peripheral smear and suggested that Mrs. N’s mild anemia was a response to the severe inflammation, siding with ID that infection and malignancy seemed to be ruled out. They signed off the case.

Prior to discharge I arranged for a biopsy of Mrs. N’s right temporal artery. Although patients with giant cell arteritis classically have headaches and scalp tenderness, it would not be the first time I’d diagnosed vasculitis of the temporal artery without these typical features. Of course, this was normal.

Further Research

That night I pulled a dog-eared copy of Petersdorf and Beeson’s article, “Fevers of Unexplained Origin,” from my files.1 Published a generation ago, in 1961, the authors reviewed 100 perplexing cases that defied simple diagnosis. The authors were the first to define a fever of unknown origin as a persistent fever greater than 101ºF, an illness of greater than three weeks’ duration and failure to reach a diagnosis despite one week of inpatient investigation. Through the years, the definition has evolved—patients don’t necessarily need to be hospitalized for their workup, and the variety of illnesses on the list has changed (e.g., abdominal abscesses were difficult to diagnose in the 1960s, but with the advent of CT scanning of the abdomen and pelvis, are much easier to identify today)—but the clarification of fevers of unknown origin remains a clinical challenge. The disorders cut across all specialties of medicine, from infectious disease to oncology, from rheumatology to psychiatry. Arriving at the correct diagnosis requires breadth of knowledge, diligence and sometimes, a dash of luck.