Rido/shutterstock.com

Settling into room 501 at Maine Medical Center, Mrs. N was on her way to the bathroom when she felt it coming on. One moment she was okay; the next, her chest felt damp and cold, even as her face flushed and her temperature spiked. Her forehead glistened beads of warm sweat. She felt the drops coalesce and roll down her cheeks and reached out to steady herself. Swaying, she half-closed her eyes and waited for the “spell” to pass. Then the shivering worsened into an uncontrollable rigor, and she shook from head to toe as if possessed. She wanted to sit, but her feet seemed stuck to the floor. Her husband stood helplessly at her side, a hand over her shoulder, the other in the crook of her elbow.

That’s when I walked in, and for the sixth time—or was it the seventh?—I had absolutely no idea what was wrong.

“Should we get blood cultures?” the medicine resident whispered in my ear.

“Sure. Call lab, and have them grab a STAT set of blood cultures,” I replied. But I knew nothing would grow out on the blood cultures. Nothing had in the past. We’ve gone through this before.

Mrs. N is an FUO—medical parlance for a fever of unknown origin—and by definition, if her disease could be diagnosed by something as simple as a set of blood cultures we wouldn’t be here five months after the onset of her illness, still searching for a diagnosis.

History

The first time I saw Mrs. N in the office the previous spring, her illness had not yet reached full expression. As I watched my nurse, Joanne, weigh and measure her, I thought: grandmotherly, reserved, no-nonsense, prim, self-contained. She was stocky, but not obese. Her silver, layered hair was offset by a gray cashmere sweater and ankle-length skirt. A rubbery squeak on the linoleum floor syncopated each step from her L.L. Bean boots. From the corner of my eye, I watched Joanne settle her into Exam Room 3.

Outside the door, I reviewed her chart. Thankfully, it consisted of only two photocopied pages; thankfully, because I’m 45 minutes behind and two pages of referral notes usually imply a simple question, such as “osteoarthritis management” or “painful left shoulder, cortisone injection.” Perhaps, I can catch up and carve out enough time to eat lunch today.

The two pages didn’t disappoint. The case appeared to be straightforward. Mrs. N was 74 years old, married, with four adult children. She was on no prescription medications. A single paragraph summarized Mrs. N’s past medical history: diet-controlled diabetes, borderline hypertension and osteoporosis. The second page described the reason for the consultation. After the onset of a sore throat and cough, Mrs. N developed generalized muscle aching and stiffness in the wrists and fingers. Her doctor wrote, “Patient miserable. Cough resolved, but joints and muscle pain keeping her awake at night. Post viral syndrome?”

I thought to myself that sounds entirely reasonable. Residual muscle and joint pain is not unusual after a viral illness. It should burn out.

I Meet the Patient

Then I opened the door. Mrs. N looked up from her Sudoku puzzle. She reached into her purse and pulled out several pages of hand-written notes. “Thank you for seeing me. I’m a mess and don’t know where to start.”

“Okay. Well, let’s begin with the last time you were well,” I suggested.

She ran a finger down the left side of the first page. “March 14. Larry, my husband, kept me up all night with a nasty cough. The next day, I was coughing, too.”

I glanced down at her chart. Of course, Larry N, a retired surgeon, was her husband. Now I remember. That’s why Dr. Hanson called me earlier this week, hoping I could fit in Mrs. N. Hmm, that rules out lunch. I settled in. Emergent spousal consults generally go in two directions, and both take a long time. Either there is hypervigilance regarding persistent but innocent symptoms, or the spouse has a rare, life-altering disorder. Mrs. N, I suspected, had a heavy dose of the former.

“So we were both sick for about 10 days. By March 24,” she moved her finger down to the next entry, “Larry was fine. He bounced back, but I took a turn for the worse. Stiff? I was so stiff I could hardly move. That’s when we decided I should see Dr. Hanson.”

“And I have his notes here,” I interjected. “The chest X-ray was okay, and basic lab, the CBC, chem profile and throat culture were all normal.” Filling in the blanks, I’ve learned, helps consolidate the story and also lets the patient know that I’ve reviewed their chart.

“Well, not really. Here.” She pointed to the chemistry profile where the BUN (blood urea nitrogen) was one point above the normal range.

I blinked. “The BUN, yes the BUN is borderline, but with the other kidney test, here,” I pointed to the creatinine on the next line, “very much in the normal range, the BUN doesn’t have any significance.”

She stared silently at me, then said, “That’s what Larry said. But it’s not normal.” I was thinking: precise, literal, uses language carefully. “So anyway, Dr. Hanson thought we both probably had a virus, but since my cough was hanging on, he prescribed azithromycin.”

“And?” I asked.

“It didn’t work.”

‘If you have a patient with an unusual prodrome you’ve never seen prior to the ultimate development of rheumatoid arthritis, you probably haven’t seen enough rheumatoid arthritis.’

Physical Exam

As she talked, I inspected her hands. She flinched slightly when I palpated several equivocally swollen knuckles on the left hand. The lungs were clear, but a faint murmur was present on her cardiac exam: Early systolic, left sternal border. Grade 2/6, the kind of innocent murmur most elderly patients develop as the aortic valve stiffens with age.

“Can you lie down?” I asked.

The shoulders and hips demonstrated pain-free normal motion. Her abdomen was non-tender. The liver and spleen were not enlarged. There was no lymph node enlargement or subtle rash. Although there was no muscle weakness, there was low-grade tenderness in the forearms. “In what way are you worse?” I asked.

“Lately, I’m sweating at night. Not every night.” She ran a finger down the page: “April 12, 18 and 21. Then, last night I was a big wet ball of sweat. And fevers? I’ve kept a graph.”

She handed me a meticulously diagrammed chart where she had recorded her temperature three and, sometimes four, times daily. For the most part, the temperatures were in the normal range throughout the day, but each evening temperatures rose to just over 100ºF.

Suddenly, the dynamics of the visit changed; night sweats and fevers five weeks into an illness are worrisome. I stuck my head out the exam door and asked Joanne to let the other patients know that I was running late. I wondered if I still had some salted nuts in my drawer.

Finishing the exam, except for the scattered swelling in several of the knuckles and low-grade tenderness in her forearms and calves, there were no clues to point toward a definitive diagnosis. I straightened up and told Mrs. N that although her symptoms might represent a persistent viral infection, we needed to look at further laboratory studies. “I know your chest X-ray was normal, but with the night sweats …”

“Larry thought you might want to get a CT scan of the chest,” she finished my sentence.

“Right. So let’s get you scheduled for that,” I replied without skipping a beat. Though Dr. N was not in the room, he seemed to be present in our deliberations. “I’m adding some immunologic labs. We’ll need a urine sample. And can I write a prescription for a long-acting anti-inflammatory? Once-daily meloxicam may help quiet down the muscle aching and joint pain.”

“Anything except prednisone,” her voice sharpened. “I once had an asthma attack, and the emergency room doctor gave me prednisone. I couldn’t sleep for a week, and my blood sugars skyrocketed. And in case you didn’t notice, I have osteoporosis. My bones are brittle enough without adding prednisone, thank you.”

Test Results Start Coming In

I ate lunch on the fly that day and immersed myself in the afternoon’s schedule of stable—and not-so-stable—patients. (I tapped a middle-aged man’s hot, swollen ankle and found gout crystals. Back-to-back lupus patients were doing well, a first for both of them. A rheumatoid patient was flaring, and we discussed adding a biologic, infliximab, to her background weekly methotrexate. An elderly man with unexplained headaches and muscle stiffness came in for his first visit after a biopsy of the temporal artery confirmed the diagnosis of giant cell arteritis.)

Late in the afternoon, I noticed the lab tech had paper-clipped Mrs. N’s lab results onto her chart and placed it squarely in the center of my desk. I sat down and finished off my apple and opened a bag of Fritos. Circled in red were two particularly worrisome results: a C-reactive protein level of 19.5 mg/dL (normal: <0.8 mg/dL) and an erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) of 110 (normal: <20). The CRP and ESR reflected extraordinarily high levels of inflammation, but didn’t clarify if this was due to a persistent infection, an immunologic disorder or an underlying malignancy. The results did, however, lay to rest any notion that Mrs. N was on the tail-end of a self-limited illness.

I pulled Joanne out of an adjacent exam room. “Can you call the medical center and set up an echocardiogram for Mrs. N?” Endocarditis, a life-threatening bacterial infection of a heart valve, would fit with Mrs. N’s clinical presentation. I ran my finger down the order sheet. Okay, good, I ordered blood cultures. I opened the next chart, but my mind refused to move on. Admit Mrs. N? Continue an outpatient work-up? I processed the available information—her healthy appearance, stable vitals and normal white blood count and kidney function—and decided to keep Mrs. N out of the hospital. For now.

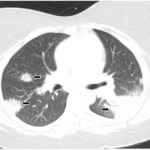

Thankfully, Mrs. N’s blood cultures were sterile. The echocardiogram demonstrated only a slightly stiff aortic valve, but no evidence of seeding by bacteria. At her follow-up visit, she had lost three more pounds but continued to look well. I reviewed the unremarkable CT scan of the chest, an important negative, because lymph node enlargement or tumors can often be missed on a routine chest X-ray. On her lab, a normal CPK and aldolase and an anti-nuclear antibody (ANA) in the normal range made a diagnosis of myositis or lupus unlikely. Likewise, with an absent anti-neutrophil cytoplasmic antibody (ANCA) and a normal urinalysis, several rare forms of vasculitis had been ruled out.

“Are your fevers and muscle and joint pain any better with the meloxicam?” I asked.

“No, not really.” There was a pause. “So … you don’t know what’s wrong with me,” she said finally, clicking her purse shut.

Internally, I was taken aback by her lack of confidence. Her ongoing fevers and sweats were a puzzle, but I was confident I’d clarify the problem. “No. Not yet,” I answered. “May I reexamine you?”

The Reexamination

She held her hands out. “My fingers are killing me.” This time, I was sure that three of the knuckles on the right hand, and two on the left hand were swollen. When I asked her to flex the fingers to the palm, she was unable to make a full fist. Roughly speaking, the synovitis in her hands was symmetric, placing her within the realm of rheumatoid arthritis (RA).

One of my partners once remarked, “If you have a patient with an unusual prodrome you’ve never seen prior to the ultimate development of rheumatoid arthritis, you probably haven’t seen enough rheumatoid arthritis.” So although it’s true that the onset of RA after a cough and sore throat is unusual, that muscle aching is not where the pathology of RA resides and that fevers are uncommon, it’s also true that for each patient who ultimately settles into what all rheumatologists recognize as classic RA, there are early non-specific threads that, in retrospect, seemed to herald the disease.

“Could I have rheumatoid arthritis?” Mrs. N asked. “Larry asked me to ask you if that’s the problem.”

I hedged. “Your blood tests, a rheumatoid factor and a CCP antibody are negative. But they’re imperfect tests, particularly early in the disease. So yes, it’s possible that this is RA.” I felt vaguely embarrassed that she was the one to bring up a diagnosis that I make routinely. The hidden presence of Mrs. N’s husband, Dr. N, hovering in the background, only added to this concern. I straightened up in my chair and pulled my shoulders back. An inaudible click in my upper neck seemed to release an unwelcome pressure.

I pressed on. “When was the last time you had a mammogram, colonoscopy or Pap smear?”

“Last month my mammogram was fine. It’s been 20 years, I don’t know, maybe longer, since my last Pap.” She pursed her lips. “Colonoscopy? Never. I don’t know why you need to …”

“I need to tell you that when we’re considering a diagnosis of what we call sero-negative RA—meaning RA without positive blood tests—we have to consider a host of RA mimics. From time to time, we’ve seen cancer trigger fevers, muscle and joint pain. It’s important to exclude this, particularly because you’re losing weight, and we don’t have a clear cause. So,” I cleared my throat, “I’d like to set you up for an outpatient colonoscopy, and you need to see Dr. Hanson for an updated Pap and pelvic exam.”

“Fine,” she said, suddenly standing.

“And,” I flipped the page on her clinic notes back to the original consult, “you’ve lost 12 lbs. since mid-March. I’m arranging for an abdominal/pelvic CT scan.”

Mrs. N sat back down. Her face was flushed. I placed the thermometer back in her mouth, 102.4ºF. “I … I don’t feel well. It’s one of those spells.” Joanne came in, and we laid Mrs. N down on the exam table and placed a damp cloth on her forehead.

“Let me call Larry. I want to admit you,” I decided.

Hospital Admission

The admission was frustratingly inconclusive. On Day 1, after blood and urine cultures were obtained, IV antibiotics were started on the recommendation of the infectious disease (ID) consultant. Again, nothing grew out. A skin test for exposure to tuberculosis was negative. A slew of laboratory studies was drawn. Tests for everything from Q fever to relapsing fever, Brucellosis, Lyme disease, HIV, ehrlichiosis, histoplasmosis, toxoplasmosis, cytomegalovirus, herpes and hepatitis B and C, were dutifully ordered and drifted back with monotonous normalcy. I asked pathology to comment on her peripheral smear; a basic test in which a sample of blood is smeared on a slide and the pathologist evaluates the sample for evidence of leukemia or parasitic infections. This was unremarkable.

Needless to say, the other studies, the CT scan of the abdomen and pelvis, the colonoscopy, the pelvic exam, a repeat echocardiogram, were non-diagnostic. On Day 4, with daily fevers continuing to spike, ID recommended that I discontinue the antibiotics. Hematology reviewed the peripheral smear and suggested that Mrs. N’s mild anemia was a response to the severe inflammation, siding with ID that infection and malignancy seemed to be ruled out. They signed off the case.

Prior to discharge I arranged for a biopsy of Mrs. N’s right temporal artery. Although patients with giant cell arteritis classically have headaches and scalp tenderness, it would not be the first time I’d diagnosed vasculitis of the temporal artery without these typical features. Of course, this was normal.

Further Research

That night I pulled a dog-eared copy of Petersdorf and Beeson’s article, “Fevers of Unexplained Origin,” from my files.1 Published a generation ago, in 1961, the authors reviewed 100 perplexing cases that defied simple diagnosis. The authors were the first to define a fever of unknown origin as a persistent fever greater than 101ºF, an illness of greater than three weeks’ duration and failure to reach a diagnosis despite one week of inpatient investigation. Through the years, the definition has evolved—patients don’t necessarily need to be hospitalized for their workup, and the variety of illnesses on the list has changed (e.g., abdominal abscesses were difficult to diagnose in the 1960s, but with the advent of CT scanning of the abdomen and pelvis, are much easier to identify today)—but the clarification of fevers of unknown origin remains a clinical challenge. The disorders cut across all specialties of medicine, from infectious disease to oncology, from rheumatology to psychiatry. Arriving at the correct diagnosis requires breadth of knowledge, diligence and sometimes, a dash of luck.

I thought back to the first day of an elective surgical rotation when I was a fourth-year medical student. The surgeon at the small southern community hospital brusquely shook my hand and said, “Internal medicine? You’re going into internal medicine instead of surgery?”

“Yes,” I said.

“You’re going to be a flea,” he drawled.

“A flea?”

“That’s right, a flea. The first to jump onto a patient and the last to get off.”

“Well,” I stammered, “that’s a good thing, isn’t it?” In internal medicine and in the practice of rheumatology, sometimes the answers don’t come easily. You’ve got to dig.

Second Opinion

Although her joint and muscle pain were only marginally improved with daily meloxicam, Mrs. N stoically refused a trial of prednisone. I sent her south for a second opinion at the Lahey Clinic in Boston. She wanted answers.

The Lahey Clinic rheumatologist suggested that Mrs. N was suffering from adult-onset Still’s disease, a rare, systemic subset of childhood arthritis that has been described in adults.

I’d considered Still’s during Mrs. N’s first hospitalization, but didn’t feel she fit the criteria for the diagnosis. Again, like so many disorders in rheumatology, there is no single conclusive test to confirm adult-onset Still’s disease. The daily fevers and intense muscle and joint pain certainly fit the bill, as did the dramatically elevated inflammatory markers—the sedimentation rate and C-reactive protein. But patients with Still’s disease also demonstrate an evanescent salmon-colored rash with the daily fevers, which Mrs. N lacked. My mind was open to the possibility of Still’s, but without the rash (the rash is so singular, it’s called a Still’s rash), we both agreed this was only one possibility among many.

Medication Trials

Mrs. N acquiesced to a trial of weekly injectable methotrexate, but was, at most, 10–20% better after eight weeks, and she discontinued the drug on her own. The sedimentation rate and C-reactive protein levels redlined as if she were taking nothing whatsoever.

Without a specific diagnosis, Mrs. N wanted to hold off on prednisone. I argued—once again—that we could easily manage elevated blood sugars if they spiked on prednisone and further, there were medications to maintain or improve bone strength if prednisone was necessary long term.

Her reply: “So you’re going to give me prednisone and two other medications for a disease you can’t name, for a duration you can’t guess, with side effects worse than the disease.”

“No,” I answered firmly. “Believe me, nothing I can give you is worse than your disease.”

She was unmoved.

Progression

Ruslan Guzov/shutterstock.com

As one month flowed into another, I began to dread the days Mrs. N was on the schedule. Each visit, she would unfold a meticulously detailed graph with the fever curve in red marker and superimposed, in black, the dates Mrs. N suffered night sweats. The intensity of joint and muscle pain—in yellow—varied day to day and week to week, mysteriously shifting from the forearms and calves to the thighs or neck. One day, her joints would be reasonably comfortable, and the next the knuckles would swell to the point she couldn’t make a fist. Increasingly, she needed her husband’s help with simple tasks: buttoning her clothes, pulling up a zipper, cutting her meat.

One busy afternoon, a new consult cancelled, and an hour opened up in the schedule. I opened up Mrs. N’s office chart, spread it out on my desk and logged onto the hospital’s electronic medical record. Maybe I’d overlooked something. At the top of a clean white sheet of paper, I wrote, “FUO” and drew arrows slanting obliquely to broad subcategories: Malignancy, Infection, Connective Tissue Diseases, Psychiatric and Miscellaneous.

Psychiatric? Although elderly, white-haired women are not immune to serious psychopathology (see Arsenic and Old Lace), I’d seen several of Mrs. N’s spells, and there was nothing to suggest fakery. On the other hand … my mind drifted back to a case of psychogenic fever of unknown origin in a woman one of my partners recently consulted on who was admitted with fevers and crops of pustular lesions on the forearms. Despite aggressive antibiotics, the fevers persisted, and new lesions erupted. The consulting service wanted to know, could she have lupus?

After cultures of the mysterious boils were sterile, after surgery incised and drained several of the most dramatic lesions, after dermatology biopsied a lesion and only non-specific inflammatory changes were seen by pathology, a simple explanation ensued. A food service worker bumped the patient’s purse off the edge of the bed, spilling half a dozen filthy needles onto the floor. The patient had been surreptitiously injecting herself with who knows what, for who knows why. Case closed.

Under the heading Malignancy, I reviewed Mrs. N’s workup to date, noting that the Lahey Clinic had picked up a PET (Positron Emission Tomography) scan on their own fishing expedition. This was an important negative, and combined with the CT scans and MRIs at Maine Medical Center, seemed to exclude malignancy as a consideration.

The normal PET scan also ruled out a diagnosis of vasculitis involving large arteries such as the aorta. On the other hand, I seemed to recall, a normal PET scan is not sensitive enough to exclude vasculitis in the smaller arteries, particularly the arteries feeding the bowels, kidneys and liver. I wrote down: Vasculitis? Abdominal angiogram?

Before moving on, I reconsidered the original hematology opinion. It came early in the workup and considered Mrs. N’s anemia to be “the anemia of chronic disease.” Because this also fit with my impression, and the peripheral smear was unremarkable, a bone marrow aspiration and biopsy were not performed. On the other hand, here we were months into the illness and still without an answer. I wrote: Bone marrow? And circled it, twice.

Have we fully ruled out infection? I wondered. With its predilection for the joints and muscles, the Chikungunya virus can be an incapacitating illness, but it’s almost never seen in the United States. Hmm, this is interesting. I flipped back to the infectious disease consult; she had vacationed in Florida the week before she and her husband became ill. I wrote down draw Chikungunya serology, knowing full well this was a rheumatologic Hail Mary.

I tapped my fingers and looked at the clock. Still 20 minutes before my next patient.

Considering Connective Tissue Diseases and Miscellaneous, I closed my eyes and returned to the possibility of adult-onset Still’s disease, aware that occasionally the characteristic rash may begin many months into the illness. But five months? I ran my finger down the outpatient lab sheet and found a ferritin level that was minimally elevated. A repeat draw two months later: minimally elevated. Still’s disease without a rash or a sky-high ferritin level? No way. I crossed out Still’s disease.

Sarcoidosis? Again, I ran my finger down the list of outpatient and inpatient labs. An angiotensin-converting enzyme level, which is sometimes elevated with sarcoidosis, was in the normal range, times two. There was no typical lymph node enlargement on the chest, abdomen or pelvis CT scans. Sarcoidosis? I wrote it down, started to cross it out, and allowed it to remain.

My mind drifted to inflammatory myopathies—a family of immune system disorders targeting the muscles and joints. Even with normal proximal strength and a persistently normal CPK and aldolase? Yes, unlikely, but still on the list. I circled the words, schedule MRI of thigh. Myositis? and added: muscle biopsy if MRI positive.

I folded up the single page and placed it in my lab coat pocket.

Unexplained?

Browsing through my collection of fever of unknown origin articles, I noticed something I’d refused to acknowledge in my previous readings: In all of the FUO reviews, from Petersdorf and Beeson’s seminal article in 1961 through the most recent review of last year, for a small subset of patients, there simply is no explanation for their illness. Whether the patient is evaluated at the Massachusetts General Hospital, a community hospital in Maine, or Guys Hospital in London, anywhere from 5–15% of those afflicted by FUO remain an enigma.

On the other hand, I smiled to myself, maybe next time I see Mrs. N I’ll be on the receiving end of the genius effect. It works like this: A patient’s illness is a conundrum. Consultant after consultant is stumped. No one can figure it out—until the last doctor palpates, say, a swollen lymph node in the neck and performs a biopsy, confirming a diagnosis of Hodgkin’s disease. The patient believes the last doctor is a genius, never considering that the disease may have evolved and the lymph node is a new finding.

The very next day, Mrs. N was admitted to Maine Medical Center. A “spell” had settled over her while she and her husband visited friends on the peninsula in Portland. Midway through a pasta dinner, a flashing wave of fever, muscle aches and profound weakness took hold. She was so incapacitated, so overcome with the pain and drenching sweats, that she crumpled onto the couch, and her hosts called an ambulance. Mrs. N was whisked off to the ER, where she lacked the energy or conviction to refuse admission.

Up in Room 501, the fever broke, and the painkillers took hold. Mrs. N insisted she was well enough to walk to the bathroom. Her husband told her to stay in bed and press the call button for help. She ignored him and stood. He shuffled to her side, one hand on her shoulder, the other in the crook of her elbow. A quiet man, he was nearly overwhelmed by the sheer impossibility that there was no definitive explanation for her illness.

She inched slowly forward. “I’m so tired; the needlesticks, the urine and blood cultures, the scans. … It’s like a, a,” she searched for the right word. “It’s like that silly movie, Groundhog Day, telling my story over and over and over.”

She didn’t see her husband reach up with his free hand and wipe his eyes. In his years as a surgeon, he’d seen his share of tough, hopeless cases. But those patients had a terminal diagnosis; they were dying from advanced cancer or virulent infections or tragic accidents. But this?

As she pivoted to sit on the commode, she shut her eyes. It was coming back. She began to shiver. A drenching icy sweat soaked her nightgown. The wrenching pain filled every muscle, every joint, every fiber of her being.

At that moment, I walked through the door with an internal medicine resident and two medical students in tow.

Mrs. N. looked directly at me, then at her husband. “I’m tired,” she repeated softly, almost inaudibly. I helped her back to bed and sat down to think. Her nurse stuck a thermometer in her mouth. “103.6º.” She entered the data into the bedside computer and handed Mrs. N two Tylenol.

Momentarily, I said nothing. The “team” awkwardly shook Dr. N’s hand while we waited for the rigors to dissipate. One of the medical students did a lovely thing; she reached over and slowly massaged Mrs. N’s neck and shoulders.

Then I pulled the white sheet of paper out of my pocket, my cheat sheet of differential diagnoses—my Rosetta Stone of diagnostic possibilities. “I have a few ideas,” I said with as much optimism as I could muster. “Let’s get started.”

An Answer Presents

“I’ve called hematology. Dr. Ebraham has set aside time tomorrow morning to perform a bone marrow test.” I adjusted my glasses. What was this? The fourth time I’d suggested steroids? “For now, I want to start a modest intravenous dose of Solu-Medrol.” I paused. “I think it will help,” I added. “It’s time.”

Her eyes remained half-closed. The covers on her bed were strewn to the side, her arms, legs and core shaking uncontrollably, as if she were possessed. She had withdrawn to that internal place where she could just barely manage the suffering. “Fine,” she replied.

There is no single conclusive test to confirm adult-onset Still’s disease. The daily fevers & intense muscle and joint pain certainly fit the bill, as did the dramatically elevated inflammatory markers—the sedimentation rate and C-reactive protein. But patients with Still’s disease also demonstrate an evanescent salmon-colored rash with the daily fevers.

I nodded to the resident, who typed in the Solu-Medrol orders. “Let’s get that first dose hung up as soon as possible,” I whispered. Although we had other patients to round on, our small group stood transfixed by the violence of her illness. In another time, perhaps, a priest would have suggested an exorcism.

When the pathologist called the next afternoon, I was fully prepared for disappointment. But there was an answer: Clusters of on-caseating granulomas were scattered throughout the specimen.

“As in sarcoidosis?” I asked.

“Yes, that is, if you’ve ruled out other causes of granulomatosis disease. It’s unusual for sarcoidosis to be confined to the bone marrow.”

I ran my hand through my hair before answering. “Well, sarcoidosis is an unusual disease. I’m good with that. Thanks.”

Sarcoidosis

Despite extensive investigation, the mystery of sarcoidosis has remained unsolved for more than 100 years. A recent case-control study (ACCESS) of more than 700 patients with sarcoidosis and nearly 30,000 relatives could not identify a single environmental, infectious agent or genetic locus to explain the pathogenesis of the disease.2 Familial clustering of sarcoidosis was first recognized 80 years ago, and various infectious triggers have been suggested, but even with increasingly sophisticated testing, no specific trigger has been implicated.

Long-Term Management

The patient, Mrs. N, initially responded well to corticosteroids, but relapsed at an unacceptably high daily dose of daily prednisone. A trial of infliximab was not steroid sparing. The patient has been on monthly IV tocilizumab and low-dose prednisone for the past two years, with good control of her disease.

Charles Radis, DO, is a rheumatologist in Portland, Maine, and director of clinical research for Rheumatology Associates.

Reference

- Petersdorf RT, Beeson PB. Fever of unexplained origin: Report on 100 cases. Medicine (Baltimore). 1961 Feb;40:1–30.

- Rybicki BA, Iannuzzi MC, Frederick MM, et al: Familial aggregation of sarcoidosis. A case-control etiologic study of sarcoidosis (ACCESS). Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2001 Dec 1;164(11):2085–2091.