Image Credit: CLIPAREA | Custom media/shutterstock.com

Recent updates to criteria used for diagnosing neuromyelitis optica (NMO) are aimed at helping physicians make the differential diagnosis of this disorder differentiating it from other inflammatory disorders—a diagnosis that can be difficult given the presenting symptoms that can mimic a number of other conditions, such as multiple sclerosis.

Published in July 2015, the new diagnostic criteria are the result of an international consensus group comprising 18 members from nine countries and co-chaired by two investigators from the Mayo Clinic.1

According to Dean Wingerchuk, MD, professor of neurology, Mayo Clinic, Scottsdale, Ariz., one of the co-chairs, the criteria were revised from the 2006 criteria to “catch up with scientific advances and align the criteria with contemporary neurological practice.”2

Dr. Wingerchuk

One specific advance has been improvement in detecting the antibody associated with the disorder—the antibody that targets aquaporin-4 (AQP4-IgG). “This antibody is highly specific,” says Dr. Wingerchuk, “so it has helped us identify a number of clinical and radiologic patterns that fall under that umbrella of neuromyelitis optica spectrum disorders (NMOSD) that weren’t previously recognized.”

The umbrella of NMOSD that Dr. Wingerchuk refers to is one of the main new changes in the update. It provides a new nomenclature to unify the terms NMO and NMOSD, with further stratification based on the presence or absence of the antibody (i.e., NMOSD with or without AQP4-IgG).

A second important change in the updated criteria is providing a way to facilitate an earlier and accurate diagnosis of NMOSD.

Facilitate Earlier & Accurate Diagnosis

Under the new criteria, neuromyelitis optica, which is an inflammatory central nervous system (CNS) syndrome, is diagnosed in patients who are AQP4-IgG seropositive with either transverse myelitis or optic neuritis. Prior diagnostic criteria required both conditions to make the diagnosis of NMOSD.

(click for larger image)

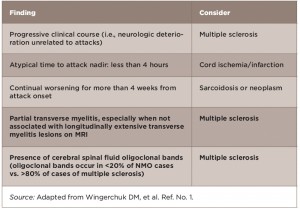

Table 1: Red Flags: Findings Atypical for NMOSD Based on Clinical & Laboratory Findings

The new criteria also identify NMOSD in patients who may present with CNS involvement beyond the optic nerves and spinal cord, and who are seropositive.

“Now, when a patient has a single attack that is consistent with an NMO spectrum disorder, and they are serum positive for the antibody, we can confirm that they have NMOSD,” says Dr. Wingerchuk.

For patients who are antibody negative, the panel provides what it calls “red flags” to guide physicians in making the differential diagnosis of NMOSD (see Tables 1–3).

Dr. Kahlenberg

Michelle Kahlenberg, MD, assistant professor of internal medicine, Division of Rheumatology, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, says she found the “red flags” particularly “useful to incorporate diagnostic clues on the likelihood of having NMOSD when antibody testing is negative.”

“Given the relapsing nature of NMOSD, you do not want to incorrectly diagnose someone with this disorder if they have another reason for their symptoms,” she says.

(click for larger image)

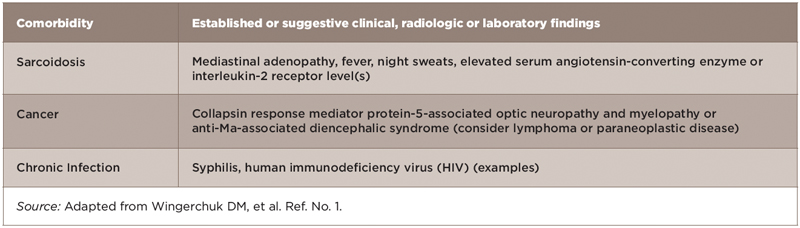

Table 2: Red Flags: Comorbidities Associated with Neurologic Syndromes that Mimic NMOSD

Dr. Kahlenberg also emphasizes that the criteria help facilitate the diagnosis of NMOSD in patients with autoimmune diseases and help tailor the appropriate treatments. “There is occasionally overlap between NMOSD and other autoimmune diseases, and knowing that a patient has NMOSD in addition to systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) or Sjögren’s may change our treatment choices and impacts the prognosis for the patient.”

(click for larger image)

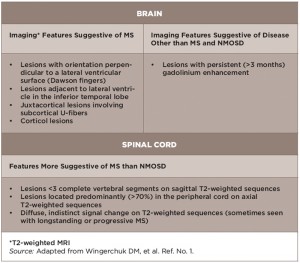

Table 3: Red Flags: Findings Atypical for NMOSD Based on Conventional Neuroimaging

Jason Kolfenbach, MD, assistant professor of medicine and program director of the Rheumatology Fellowship Program, University of Colorado, Denver, also emphasizes that the inclusion of the red flags is particularly helpful to remind clinicians of potential alternative causes of CNS disease, particularly in cases that may not be a classic presentation for NMOSD.

“This is important because clinical symptoms and the underlying etiology that could be identified by the red flags would be treated with potentially much different medications,” he says.

Serologic Testing

The holy grail of NMOSD diagnosis is serologic testing for serum AQP4-IgG. The gold standard, according to Dr. Wingerchuk, is the cell-based assay used by the Mayo Clinic and a few other laboratories. More widely used and accessible is the ELISA technique, which, says Dr. Wingerchuk, has good sensitivity but less than optimal specificity.

Dr. Kahlenberg, who uses the serum test in patients with a clinical suspicion for NMOSD (e.g., MRI lesions or presenting with progressive weakness), says she has not had any issues with insurance coverage for the test and routinely obtains the antibody testing through reference labs.

Dr. Kolfenbach also says that most centers have access to testing either on site or by sending it out to reference laboratories, but emphasizes that cell-based assays are not available at most centers.

Dr. Wingerchuk emphasizes that most commercial laboratories still use the ELISA technique, saying that it is a good technique, but because of its less-than-optimal specificity (compared with the cell-based technique), it can generate false positives. Therefore, he recommends use of the cell-based assay when possible.

Common Scenarios for Rheumatologists

One common scenario that rheumatologists may encounter when seeing a patient with NMOSD, says Dr. Wingerchuk, is a patient with spinal cord inflammation or transverse myelitis. If the patient has multiple sclerosis, MRI lesions would tend to be smaller and shorter in the spinal cord, whereas they would be longitudinally extensive and extend over three or more vertebral segments of the spinal cord in patients with NMOSD. If the latter was found, that would trigger obtaining the antibody test.

The holy grail of NMOSD diagnosis is serologic testing for serum AQP4-IgG. The gold standard, according to Dr. Wingerchuk, is the cell-based assay used by the Mayo Clinic & a few other laboratories.

“In rheumatology practice that would be important because some of these patients who have NMOSD also have some of the rheumatologic antibodies or even rheumatologic diseases, especially lupus or Sjögren’s disease,” he says. “So sometimes when patients have neurologic involvement, it is ascribed to their rheumatologic involvement, when in fact they have coexisting diseases. They have NMO spectrum disorder and lupus, for example.”

Dr. Kolfenbach

Dr. Kolfenbach also emphasized the patients with autoimmune disease are at risk for a second, or even a third, concurrent autoimmune illness. In a prior study of patients with rheumatologic disease and CNS inflammatory manifestations, he and his colleagues found a high percentage of patients with both rheumatic disease and concurrent NMOSD.3 “There tends, in NMO, to be higher rates of concurrent autoimmune disease,” he says, adding that neurologic involvement may present before, after or concurrently with a diagnosis of rheumatic disease. “We may be following a patient with lupus or Sjögren’s disease who then is unlucky enough to develop this second autoimmune disease, so rheumatologists are becoming well versed in this condition as well,” he says.

Message to Rheumatologists

“Our patients are at unique risk for this special neurologic disease,” emphasizes Dr. Kolfenbach. “It is not a condition that only neurologists think about, but it is something that rheumatologists need to be aware of in our patients because they are at higher risk.”

Dr. Kolfenbach emphasizes that rheumatologists have a role in assessing patients with potential NMO because these patients may have an unidentified rheumatic condition. “One of the red flag conditions mentioned in this paper, sarcoidosis, is a condition commonly managed by rheumatologists,” he says. “Also, many of our diseases such as lupus, Sjögren’s syndrome, Behçet’s disease, anti-phospholipid antibody syndrome and others can be associated with CNS involvement.”

As such, he encourages “neurologists to consider a concurrent disease in these patients and refer them to a rheumatologist for a full evaluation.”

Dr. Wingerchuk agrees, stating that one of the most common scenarios is neurologists referring a patient to rheumatologists to help them find a rheumatologic disease in a patient who has some positive autoimmune antibodies. “This is the recognition that sometimes you see a cluster of antibodies occur in these patients with NMO and checking out these antibodies is reasonable.”

Mary Beth Nierengarten is a writer, editor and journalist with more than 20 years of experience writing about clinical medicine and health-related issues, and lives in Minneapolis.

References

- Wingerchuk DM, Banwell B, Bennett JL, et al. International consensus diagnostic criteria for neuromyelitis optica spectrum disorders. Neurology. 2015 Jul 14;85(2):177–189.

- Wingerchuk DM, Lennon VA, Pittock SJ, et al. Revised Diagnostic Criteria for Neuromy-Elitis Optica. Neurology. 2006 May 23;66(10):1485–1489.

- Kolfenbach JR, Horner BJ, Ferucci ED, et al. Neuromyelitis optica spectrum disorder in patients with connective tissue disease and myelitis. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken). 2011 Aug;63(8):1203–1208.