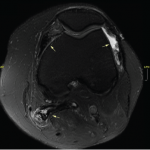

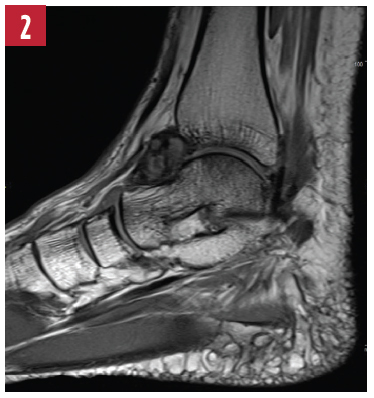

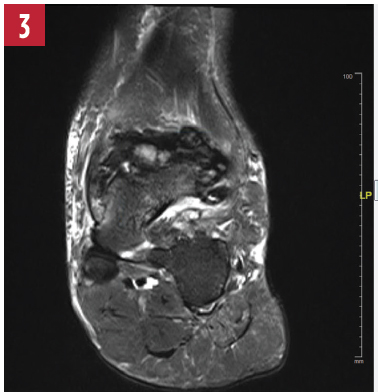

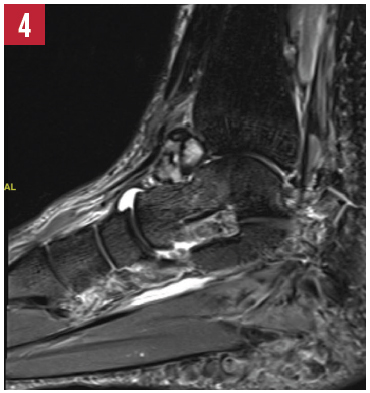

Radiographic imaging showed circumferential soft tissue swelling of the ankle with a soft-tissue density seen in the tibiotalar and posterior subtalar joints, as well as a large, lobulated effusion. MRI of the left ankle shows cystic changes within the talus and first cuneiform bones, as well as a lobulated abnormal soft tissue density with low signal intensity within the tibiotalar and subtalar joints. The MRI suggested a diagnosis of pigmented villonodular synovitis (PVNS) with associated subchondral erosions, a diagnosis that was confirmed by ultrasound-guided synovial tissue biopsy.

PVNS is an uncommon disorder of unknown etiology, affecting synovial and tenosynovial tissues. It is more common in women than in men. There are two major types of PVNS: diffuse and localized. Diffuse PVNS presents as indolent and progressive enlargement of the entirety of a single joint. The knee is the most commonly affected joint, followed by the ankle and the hip. When PVNS affects the tendon sheath of a digit, it is often referred to as a tenosynovial giant cell tumor. Rarely, PVNS can affect the spine. Localized PVNS occurs less frequently than the diffuse PVNS, and affects only a portion of the synovium in one joint. The affected portion can project into the joint space, which can cause a patient to experience a foreign body sensation, such as locking, clicking or catching. Pain is less common in localized PVNS. Aspiration of any effusion associated with PVNS classically produces dark, hemosiderin laden fluid. The appearance of such fluid in the absence of antecedent trauma should prompt consideration of the presence of PVNS.

Often, radiographs will not identify PVNS. Non-contrast MRI will show a dark, soft tissue mass with low-to-intermediate signal intensity on T1-weighted imaging, and low signal intensity on T2-weighted imaging, as a result of hemosiderin deposition in synovial tissue. Additional findings of scalloped erosions with sclerotic changes at sites of synovial insertion can be seen in cases of prolonged PVNS.

Treatment of localized and diffuse PVNS is surgical resection of the lesion and affected synovium. Without complete synovial resection, recurrences occur frequently. Adjunctive intra-articular radiation or external beam radiation therapy may reduce the risk of PVNS recurrence, especially in cases of diffuse disease refractory to initial surgical resection. In cases of advanced diffuse PVNS, when there is invasive destruction of bone, the gold standard of treatment is complete synovectomy with total joint arthroplasty. Vertebral involvement of PVNS can be difficult to treat with surgery. There are a few reports of successful treatment of PVNS with the tyrosine kinase inhibitor imatinib mesylate or anti-TNF agents.

X-ray of the left ankle.

T1-weighted image of the left ankle.

T2-weighted image of the left ankle.

STIR image of the left ankle.

Cianna Leatherwood, MD, is a rheumatology fellow at Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston. Clinical and research interests include SLE and healthcare disparities.

Derrick J. Todd, MD, PhD, is a staff rheumatologist at Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston, and director of the Brigham and Women’s Rheumatology Musculoskeletal Ultrasound Center. Areas of clinical expertise include MSK ultrasound and adolescent rheumatology for patients transitioning from pediatric to adult rheumatology care.

Send us your images

Contact us at:

Simon Helfgott, MD, physician editor

Email: [email protected]

Keri Losavio, editor

Email: [email protected]

References

- Chin KR, Barr SJ, Winalski C, et al. Treatment of advanced primary and recurrent diffuse pigmented villonodular synovitis of the knee. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2002 Dec;84-A(12):2192–2202.

- Kramer D, Frassica F, Frassica D, Cosgarea A. Pigmented villonodular synovitis of the knee—diagnosis and treatment. J Knee Surg. 2009 Jul;22(3):243–254.