Tefi/shutterstock.com

CHICAGO—Celiac disease—the gluten-induced illness that can be seen alongside rheumatic diseases—has been seen much more commonly over the past 20 years than it was previously, but the illness can come with questions that are not always straightforward, an expert said at the ACR’s State-of-the-Art Clinical Symposium.

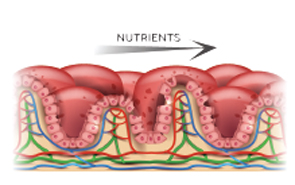

The disease, in which the small intestine becomes inflamed in genetically predisposed people and resolves when they stop eating gluten, used to be thought of as a very rare disorder typically seen in infancy and almost unheard of in North America, said Joseph Murray, MD, professor of gastroenterology at the Mayo Clinic.

The disease now manifests in both adults and children, occurs around the world, shows itself in a variety of ways and is no longer thought to be so rare in the U.S. For example, in Olmsted County, Minn., the county in which the Mayo Clinic is located, the incidence of celiac disease went from close to zero in the 1950s to between 15 and 20 per 100,000 person-years, where it has plateaued for a couple of decades, Dr. Murray said.

“It stayed at a level that’s about 20 times higher than what it was prior,” he said.

According to a study based on data from the U.S. National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, about 1.8 million people in the U.S. have celiac disease, although most are undiagnosed and are not on a gluten-free diet, he said. A similar number of people, interestingly, are on a gluten-free diet, but do not have celiac disease.

Dr. Murray

“The irony is, those who have celiac disease are not diagnosed, most of them, even though they would probably benefit from being on a gluten-free diet; whereas, those who are on a gluten-free diet without the diagnosis—it’s uncertain that they even need or benefit from the diet,” Dr. Murray said.

About a quarter of cases present as classic malabsorptive syndrome, with such symptoms as diarrhea, steatorrhea, weight loss and other problems. About half present as mono-symptomatic, with anemia, diarrhea, lactose intolerance or some other symptom. Another quarter of the patients present with a non-gastrointestinal problem, such as infertility, bone disease, neurological disease, shortness of stature or brittle diabetes.

Rheumatic diseases in which celiac disease is seen include inflammatory myositis, sarcoidosis, juvenile arthritis and primary Sjögren’s syndrome. Some patients also develop a fibromyalgia-like disorder, Dr. Murray said.

A frequent misconception is that a positive HLA finding means that someone has the disease.

Diagnosis

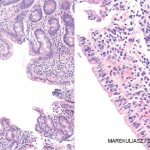

A celiac serology test is used for initial detection and as an adjunct to diagnosis, but the gold standard for diagnosis is villous atrophy, or a flat-appearing pathology, with chronic inflammation, in the proximal small intestine while on a gluten-containing diet.

The most important serology test is the tTGA, and the higher the titer meaning the stronger the likelihood of celiac disease.

Controversy has arisen over the need for a biopsy in certain patients to make a diagnosis. The European Society of Pediatric Gastroenterology Hepatology and Nutrition has issued criteria saying that children could avoid a biopsy if they have symptoms suggesting the disease, if their tTGA is 10 times the upper normal limit and on a separate blood draw, if they are endomysial antibody positive and carry the HLA genes of either DQ2 or DQA. They also, of course, must respond to a gluten-free diet.

But others caution that some practitioners ignore these criteria. They also say that having a baseline histology can allow for the severity to be tracked, that some centers will not prescribe a gluten-free diet unless the diagnosis is proved and that a fully proved diagnosis has implications for family members, because up to 10% of first-degree relatives are affected.

Dr. Murray, along with Steffen Husby, MD, of Odense University Hospital in Denmark, has issued a kind of compromise approach: If the tTGA test is highly positive, then a positive endomysial test and positive HLA test means they can be considered to have celiac disease. If the tTGA test is negative, they probably do not have the disease. And if the tTGA is in the borderline range, then do a biopsy if their HLA test is positive. If the HLA test is negative, they can’t have the disease.

“So when you tell a patient your tTG is positive—your test for celiac is positive—say, ‘Please don’t start the gluten-free diet until you’ve got your biopsy done because it can go negative, especially in younger patients,’” Dr. Murray said.

Rheumatic diseases in which celiac disease is seen include inflammatory myositis, sarcoidosis, juvenile arthritis & primary Sjögren’s syndrome. Some patients also develop a fibromyalgia-like disorder, Dr. Murray said.

Dr. Murray said that a frequent misconception is that a positive HLA finding means that someone has the disease.

“Often that’s the most common problem I see: ‘Oh, my kids all have the genetic type; they’re all on a gluten-free diet.’ The parents have equated that with the disease, and that’s just not true,” he said.

Most people with the at-risk types will not have celiac disease, he said. Two-thirds of family members of those with the disease will carry the at-risk types, but most don’t get the disease.

Case Study

Sometimes, even a biopsy might not necessarily mean someone has celiac disease. In one of his cases, an 80-year-old woman came to him with a three-year history of occasional diarrhea and weight loss. She was gliadin antibody positive but tTG and endomysial antibody negative. A duodenal biopsy resulted in a celiac disease diagnosis.

Despite being compliant with a gluten-free diet, the woman kept regressing after periods of feeling better. Follow-up biopsies were unchanged.

Dr. Murray found that the woman had been traveling to a tropical country frequently to visit her sister, who was a missionary there. She was diagnosed with tropical sprue, which also causes malabsorption of food. It cleared up after she began taking the right medication.

“This illustrates that gliadin antibodies are not specific for the disease and that all that flattens is not celiac disease,” he said. “So even in that case, be careful.”

False Positives

Tropical sprue isn’t the only thing that can cause a false positive on a biopsy. Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, self-limited enteritis, combined variable immunoglobulin deficiency including that seen after Rituxan (rituximab) use, and autoimmune enteropathy all can bring about similar pathology.

He also cautioned that olmesartan use can bring about an enteropathy that mimics celiac disease, he said. So when patients present with symptoms, stopping the drug should be a consideration, Dr. Murray said, though he added that this association is rare and that physicians should not be hasty in stopping the drug.

Even though “gluten-free diet” is something that “trips right off the tongue,” Dr. Murray said it’s important to remember that patients need support to stay on the diet—and to be careful with non-food products, including cosmetics, that could contain gluten.

“It’s a lot harder to undertake,” he said, “than it is to tell people to do it.”

Thomas R. Collins is a freelance medical writer based in Florida.