The funding outlook in the United States for the biological sciences in general, and for medical sciences in particular, is bleak. The last few years have been very challenging for the research community in the United States because a tight federal budget has significantly decreased the growth of the National Institutes of Health (NIH). Indeed, success rates are currently in the single digits for some grant programs at the NIH and National Science Foundation (NSF), and programs funded by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) are also in jeopardy. While the total number of applications has significantly increased since fiscal year (FY) 2002, success rate, total number of grants awarded, and total dollars committed to research have dropped steadily – and the decline was precipitous in 2005.

This year, NIH will likely not receive any increases in funds, resulting in a cumulative loss of purchasing power of 8.3% since 2004. While national defense spending has reached close to $1,600 per capita, federal spending for biomedical research amounts to approximately $97 per capita. The scientific community in the United States depends on federal funds to perform research. Indeed, it has been mostly federal funding for biomedical research that has fueled discoveries leading to significant advances in the understanding of human disease and the development of effective diagnostic tools and therapies.

An area of great concern is the individual researcher grants, called RO1s. A majority of important biomedical science discoveries in the United States have come from independent investigator laboratories funded by RO1s. The cost of interrupting support to an independent laboratory can be substantial. Currently, nearly 75% of researchers who apply for NIH RO1 funding do not succeed. In 2005, 27.6% of applications received funding, down from 35% in 2000. RO1 applicants are allowed to submit a specific application up to three times. Each time a rejected application is revised, it delays the time required before support can be approved and research initiated by close to a year. Because the grant application process is slow and uncertain, it often leads otherwise promising and successful investigators to re-evaluate and change careers. It can also result in the dissolution of teams of highly trained personnel.

For new submissions, an overall success rate of 9% was calculated for FY 2005. Further, the budget for existing grants was cut by 2.35% in 2006 to free up money for new grants and grants competing for renewal. Some funded grants were required to cut administrative costs by 20%. It becomes very difficult, if not impossible, for peer review to discriminate among applications and accurately select only one of 11 for funding. Grants are not only more difficult to obtain now, but also more difficult to renew. While FY 2006 data are not yet available, a trend toward further diminished RO1 support is evident because the total NIH allocation was less than the biomedical inflation index.

Consequences of Disappearing Federal Funds

- Decreases in advances in the understanding of human disease and the development of diagnostic tools and therapies;

- Loss of highly skilled and trained personnel due to career changes and dissolution of research teams; and

- Fewer individuals selecting careers in biomedical research.

Biomedical Belt Tightening

Reasons for this tightening biomedical budget include a ballooning federal deficit; 3% to 5% annual inflation in biomedical research costs; a political mandate that has shifted towards military, defense, and security spending; and an increased demand for grant funding. Indeed, there has been an explosive growth in grant applications. In 1998, the NIH received 24,000 grant applications, while in 2006 it received 46,000. Average grant sizes have also grown substantially and, because Congress stopped increasing the NIH budget, its buying power has fallen significantly.

A shift in the allocation of NIH dollars has significantly decreased the percentage of NIH budget devoted to independent investigators. From 1998 to 2005, there was almost a 6% decrease in the percentage of the total NIH budget that went to independent investigator grants. While it is unclear what the balance should be between shifting funds to multi-center projects (including multi-center clinical trials or genome projects) and maintaining adequate independent-investigator research, it is important to remember that the main force that drives translational research and clinical trials is the independent investigator.

Importantly, it is the independent investigator who trains the next generation of researchers. Decreased funding success leads to a loss of competitiveness and sends a disheartening message to potential future generations of researchers. Fewer graduate students and subspecialty fellows might elect to remain in academia as the number of potential role models decreases. A new investigator missing the pay line after several attempts can end a potentially promising career and waste the costly investment of training a young scientist. New investigators are particularly hurt by the budget situation. For example, the average age at first RO1 grant is now 42, up from 34 in 1980. At that time, approximately 25% of RO1 grants went to researchers younger than 35, while today it is approximately 4%. This causes problems in faculty recruitment, retention, and renewal.

While national defense spending has reached close to $1,600 per capita, federal spending for biomedical research amounts to approximately $97 per capita.

Future Implications

These trends are quite ominous for the future of U.S. research. Most biomedical research innovation typically comes from young researchers working in small and mobile research groups. The vitality of these young investigators must be preserved at all costs. The factors mentioned above have made careers in biomedical research increasingly unattractive for young people. We must assure that a new generation of scientists obtains adequate resources to carry on the research. Unfortunately, NIH training grants, a major source of support for postdoctoral and clinical fellows during their research experience, have also been affected. Trainees might opt for other career paths as a result, further decreasing the pipeline of future investigators.

This issue raises serious concerns about the future of U.S. biological and medical sciences, because the RO1 grant is an essential contributor to scientific innovation. Recent discoveries have provided potential opportunities for science, but we might not be able to take full advantage of these breakthroughs. It is already evident that the United States’ contribution to science in general and biomedical sciences in particular is decreasing, and federal decreases in funding will accelerate this process.

Trends in Rheumatology Dollars

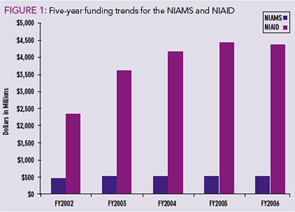

Arthritis is the leading cause of disability in the United States and nearly 43 million Americans – about one in every five adults – have arthritis or chronic joint symptoms. As the population ages, these numbers will probably increase dramatically. Each year, arthritis costs billions in medical care and indirect expenses such as lost wages. Currently, the budgets for the two institutes that fund the majority of rheumatology-related grants – the National Institute for Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases (NIAMS), and the National Institute for Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID) – have ongoing decreases in their budget and pay lines.

The NIH is currently operating under a continuing resolution and it is unclear when a final appropriation will be given. Currently, for NIAMS and NIAID, only RO1 grants that fall in the 10th percentile are receiving funding from these institutes. Other types of grants have also seen significant reductions. NIH funding specifically assigned to arthritis research was $380 million in 2003 and gradually fell to about $361 million in 2007. Adjusted for inflation, this is a sharp decrease. Similarly, funding for autoimmune diseases in general fell from $591 million in 2003 to $584 million in 2007. Similar striking trends have been seen for specific systemic autoimmune diseases, such as lupus and scleroderma. While autoimmune diseases affect 10% of the general population, they account for only 2% of NIH funding.

What Can You Do?

- Take a proactive approach and establish contact with your senators and representatives and their staff to advocate for research funding increases. To determine your legislators, go to http://www.rheumatology.org/actioncenter and enter your zip code.

- Contact the ACR Government Affairs Committee to participate as an Advocate for Arthritis: www.rheumatology.org/advocacy/federal/advocates.asp.

- Inform your colleagues, peers, and patients about the current status of federal research funding and encourage them to take a proactive approach.

- Learn more about the ACR’s political action committee (PAC) to enhance rheumatology’s presence on Capitol Hill. Contact Kristin Wormley at [email protected] for more information.

Pediatric Research Funding

Childhood arthritis is the number-one cause of acquired disability in children and the sixth most common childhood disease. It is estimated that 300,000 children in the United States suffer from some form of arthritis or rheumatic disease. Many childhood rheumatic diseases are different from those that start in adulthood, yet most pediatric rheumatic diseases are treated with the same drugs used in adults. Basic research and clinical trials in pediatric rheumatology are the only way to find the specific causes and the right treatments for these diseases. Less than 2% of the annual NIAMS budget was allocated to support pediatric rheumatology research in the past four years. Currently funded projects include 11 basic and eight clinical trial/translational research projects, distributed among half of the 25 ACGME-accredited pediatric rheumatology divisions across the United States.

The current budget is clearly insufficient to address the scientific challenges in the field. NIAMS leads the main research effort in pediatric rheumatic diseases, and a further decrease in its FY 2007 budget will definitely have an effect on the already slim funding of arthritis and related rheumatic diseases in children. It will hamper basic research and patient care both in the short term – by not providing novel therapies – and even more importantly in the long term – by not training a new generation of pediatric rheumatologists to conduct clinical research.

The ACR supports a proposal to triple NIH funding for FY 2008 and provide annual increases in the NIAMS budget, and opposes the use of budgetary mechanisms that arbitrarily limit research funding. The ACR also supports the National Arthritis Action Plan and arthritis-related funding activities from the CDC.

Interestingly, very few scientist and physicians are taking a proactive approach to ask Congress to increase the NIH budget. This passivity has been explained in a number of ways, including lack of time, ignorance on how to proceed to press for additional funding, and a misconception that other people are engaged so there is no need for a scientist or physician to get involved. It is imperative that more voices be heard so that we do not encounter a lost generation of researchers and the implications this has for healthcare and biomedical science development. Voices of physicians and scientists are needed to send a message to Congress that these severe cuts in federal research funding are jeopardizing very important advancements in biomedical research. Assuring a vital research workforce for the future is imperative for the health of the United States.

Dr. Kaplan is assistant professor in the division of rheumatology at the University of Michigan in Ann Arbor. Dr. Pascual is associate investigator at Baylor Institute for Immunology Research (Texas).