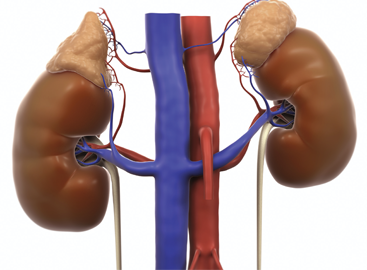

ACTH is a hormone that tricggers the adrenal glands, on top of the kidneys, to produce cortisol, replicating the effects of taking prednisone.

Science Picture Co / Science Source

As rheumatologists, we have a love-hate relationship with the corticosteroid prednisone, a feeling many of our patients share. It’s our most effective medication to quickly shut down an overactive immune system. When we have a patient with life- or organ-threatening autoimmune disease—severe lupus affecting the kidneys or vasculitis causing hemorrhage in the lungs, for example—large doses of prednisone are the most immediate treatment and are considered the standard of care. When a patient has a flare of rheumatoid arthritis, a moderate dose of prednisone can make a remarkable difference within a few days. Among patients with polymyalgia rheumatica, even tiny daily doses of prednisone can make patients with severe muscle pain and stiffness feel normal for years.

But prednisone can also cause significant harm. Taking high doses can raise blood pressure and blood sugar, significantly increasing the risks for cardiovascular disease and diabetes. Long-term use can reduce bone strength, increasing the risk for hip, spine and other fractures due to osteoporosis. In patients with lupus, high doses of prednisone often lead to avascular necrosis (dead bone in the hips and other large joints), a condition that can be remedied only by total joint replacements. And because prednisone suppresses the body’s immune system, taking it can also result in a substantial increase in the risk of mild to serious infections.

A medication that offers the benefits of prednisone without its side effects would be a tremendous breakthrough in rheumatology. This is essentially what every tested immunosuppressant drug is trying to be—thus far unsuccessfully.

Patients, insurers, prescribers & the FDA should mandate large-scale, randomized, prednisone-controlled trials of Acthar prior to allowing further prescriptions for rheumatic indications.

Enter Acthar. Or to be more precise: re-enter adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH), albeit in an astronomically expensive form.

ACTH is a hormone released by your brain that triggers your adrenal glands to make cortisol, which is the body’s equivalent of prednisone. The ACTH molecule was discovered in the 1930s by a group of biochemists trying to understand the different chemicals produced by the pituitary gland.1 Interest in using ACTH therapeutically arose after Nobel prize-winning work by Philip Hench, MD, in the 1950s demonstrated the efficacy of cortisol, reconfigured as prednisone, in suppressing immune-mediated inflammation.2 ACTH works by inducing the patient’s adrenal glands to release cortisol, thereby replicating the effect of taking prednisone. Because of this, it very likely has risks and benefits similar to those of prednisone.

The formulation of ACTH now known as Acthar was originally approved by the FDA prior to the 1962 Kefauver-Harris Amendment, which requires that drug developers provide evidence from randomized clinical trials to demonstrate efficacy as a condition of gaining approval for marketing. So Acthar was, as we say, grandfathered in without undergoing a scientifically rigorous evaluation. Because the drug was originally approved for a wide range of autoimmune diseases, the manufacturer does not need to complete trials to demonstrate safety or efficacy.3 In this way, Acthar has indications for a wide range of rheumatic diagnoses: rheumatoid arthritis, lupus, dermatomyositis and polymyositis, sarcoidosis, gout and uveitis.

Acthar is being marketed as the new and improved prednisone, but this characterization is not supported by the facts. Most importantly, it has not been tested head to head with prednisone except for a few small studies on ACTH for infantile spasms. Given this lack of data, we simply have no way to know how the efficacy of Acthar compares with prednisone for the vast majority of indications listed on the drug label. In addition, Acthar’s safety has not been compared to that of prednisone. Patients have told us they are on it because “it isn’t supposed to increase hypertension” like prednisone, but this claim is not justified by the available data or by the expected physiology of the drug.

Now would be a good time to note the tremendous difference in cost between prednisone and Acthar: According to GoodRx.com, a one-month supply of prednisone 60 mg a day (a very high dose) costs less than $25, while a one-month supply of Acthar 80 mg twice a week (an average dose) is around $80,000. Doing the math, that makes Acthar 3,200 times more expensive than the standard therapy, despite a lack of evidence demonstrating any advantage in terms of safety or efficacy.