Updates from the ACR Convergence 2023 Review Course, part 4

The Review Course drew quite the crowd on Saturday morning at ACR Convergence 2023.

SAN DIEGO—Under the leadership of moderators Noelle Rolle, MBBS, assistant professor in the Division of Rheumatology, associate program director of the Rheumatology Fellowship at the Medical College of Georgia, Augusta University, and Julia Schwartzmann-Morris, MD, associate professor, Donald and Barbara Zucker School of Medicine at Hofstra/Northwell, Great Neck, N.Y., the one-day Review Course held before ACR Convergence 2023 officially kicked off on on Saturday, Nov. 11, covered a plethora of important topics.

Relapsing Polychondritis

Marcela Ferrada, MD, who most recently was on faculty with the National Institutes of Health (NIH), Bethesda, Md., discussed relapsing polychondritis (RP), a condition that she herself has and for which she serves as a passionate advocate.

RP is a rare, heterogeneous, systemic inflammatory disease that targets cartilage. The diagnosis is a clinical one and commonly involves auricular chondritis, and redness and pain of the cartilaginous structures of the nose. Dr. Ferrada made a point of noting that the nose in these patients can look normal, but can still be quite painful; she also explained that we still are without a formal system of defining and grading ear chondritis.

Patients with RP may have upper airway disease, in the form of subglottic stenosis, or lower airway disease, which can manifest with tracheomalacia. Bronchial obstruction can also occur in some patients. With regard to musculoskeletal manifestations, a non-erosive arthritis can occur, although Dr. Ferrada suspects this may actually be a form of tenosynovitis rather than a true arthritis. Patients with RP may, uncommonly, experience severe scleritis; episcleritis is more common and typically less severe. There can also be inner ear involvement, with subsequent hearing loss and tinnitus.

Diagnosis

Dr. Ferrada shared a number of clinical pearls that help clarify misunderstandings about diagnosing RP. First, she noted that antibodies against type II collagen are not of much utility; in fact, the initial report of the possible association of these antibodies with RP was from an article in the 1970s that included only 15 total patients.

Second, biopsy is not required to diagnose RP, but it can be helpful and sometimes necessary to exclude infections or other diseases if they are suspected. This is an important point because performing a biopsy in a patient with RP can trigger a flare of the disease.

Third, inflammatory markers can be normal in patients with RP, even when the disease is active, thus a normal erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) or C-reactive protein (CRP) does not rule out the diagnosis.

Typing RP

Dr. Ferrada presented compelling data to show that what we call RP may actually be more than one disease, or at the very least has several distinct subtypes. In a landmark paper on the subject, Dr. Ferrada and colleagues identified three subtypes of RP.

Type 1 RP is less common, but can be severe and is characterized by chondritis, tracheomalacia, saddle-nose deformity and subglottic stenosis. These patients tended to have the shortest time to diagnosis, highest disease activity and most frequent need for intensive care unit admission and tracheostomy.

Type 2 RP is characterized by tracheomalacia and bronchomalacia, but not saddle-nose deformity or subglottic stenosis; these patients have the longest time to diagnosis.

Type 3 RP is characterized by tenosynovitis/synovitis and ear chondritis.1

Across all three subtypes of patients, it is important to ask about a history of oral and genital ulcers; some of these patients may actually have a condition called mouth and genital ulcers with inflamed cartilage (MAGIC) syndrome. On that note, the presence of oral and genital ulcers may also imply the possibility of Behçet’s disease, although this condition does not normally have cartilaginous involvement as well.

Dr. Ferrada made note of the work from Dion and colleagues in 2016 that identified a subgroup of patients with RP with unusual hematologic findings.2 These data were shown to be significant in 2020 with the first description of VEXAS syndrome, which is an adult-onset inflammatory syndrome due to a somatic mutation in the UBA1 gene that can present with fevers, cytopenias, vacuoles in myeloid and erythroid precursor cells, dysplastic bone marrow, neutrophilic cutaneous and pulmonary inflammation, chondritis and vasculitis.3 It is estimated that about 8% of patients with RP have VEXAS and about 60% of patients with VEXAS have RP. Thus, if you see a patient with ear and nose chondritis with a mean corpuscular volume (MCV) greater than 100 fL and a platelet count less than 200,000/μL of blood, it’s important to highly consider the possibility of VEXAS and refer for genetic testing.

Treatment

In terms of treatment for RP, Dr. Ferrada noted that, unfortunately, a standard of care does not exist at present. Medications that are frequently used include corticosteroids, methotrexate, mycophenolate mofetil, leflunomide, TNF-α inhibitors and interleukin-6 (IL-6) inhibitors. Dapsone has been used in patients, but Dr. Ferrada prefers to avoid this medication because it can cause hemolytic anemia and methemoglobinuria.

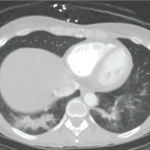

Baseline tests for patients with RP should include audiometry, dynamic computed tomography (CT) of the chest and echocardiogram. Additional testing, such as laryngoscopy and bronchoscopy, may be indicated based on symptoms in specific patients.

Jason Liebowitz, MD, is an assistant professor of medicine in the Division of Rheumatology at Columbia University Vagelos College of Physicians and Surgeons, New York.

References

- Ferrada M, Rimland CA, Quinn K, et al. Defining clinical subgroups in relapsing polychondritis: A prospective observational cohort study. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2020 Aug;72(8):1396–1402.

- Dion J, Costedoat-Chalumeau N, Sène D, et al. Relapsing polychondritis can be characterized by three different clinical phenotypes: Analysis of a recent series of 142 patients. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2016 Dec;68(12):2992–3001.

- Beck DB, Ferrada MA, Sikora KA, et al. Somatic mutations in uba1 and severe adult-onset autoinflammatory disease. N Engl J Med. 2020 Dec 31;383(27):2628–2638.