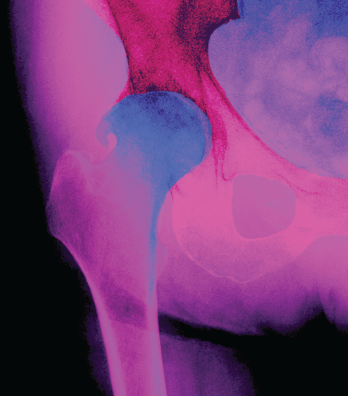

Living Art Enterprises, LLC / science source

CHICAGO—The placebo effect in treating pain in osteoarthritis (OA) should not be discounted, an expert said at the ACR State-of-the-Art Clinical Symposium in April.

It’s especially important to accept the effect as real considering that trials of pain therapies in OA generate such high placebo effects (typically at least 40%) and that OA treatment options, especially for prevention of structural progression, remain scarce, with little demonstration of efficacy in platelet-rich plasma therapy, stem cell therapy and prolotherapy, said Joel Block, MD, director of rheumatology at Rush Medical College in Chicago.

Because OA progresses slowly, over decades, studying structural progression in the span of a typical trial is “almost impossible,” Dr. Block said. “Demonstrating an advantage is difficult.” The heterogeneous way in which the disease presents across populations, the confounders seen in the elderly population, the challenges of attrition and how to assess progression are other hurdles, he said.

“That’s why as of today, in 2018, there are absolutely no agents that have been shown to effectively modify the structural progression in humans with OA,” he said.

Drugs originally investigated to slow structural progression, such as hyaluronic acid, have been repurposed for pain and functional improvement, he said. Many have been found to have low effect sizes, but that’s because they’re being compared with placebo, Dr. Block said.

“You might conclude the word placebo is a misnomer when dealing with OA and, maybe, other chronic pain conditions,” he said. “Placebo itself is active treatment by all the criteria we use to define active treatment.” It provides substantial symptomatic relief, has a high effect size and shows durable results, he said.

A formal systematic analysis in 2016 that included 215 OA trials found that, on average, 75% of pain reduction was due to the placebo effect.1

“You need to keep the placebo in mind if you’re going to evaluate new treatments,” Dr. Block said.

Patients will continue to use complementary and alternative medications even after hearing the data clearly show they’re ineffective, he noted. “The reason they do is that they’re actually getting relief,” he said. “That sets up competing imperatives. As a biomedical scientist, it’s my job to demonstrate that an agent is better than placebo, but that assumes the placebo is inactive. When I see patients in the office, it’s quite different. My job is to palliate pain among individuals. I don’t care what the science says, necessarily. Therefore, when I’m evaluating the utility of a novel OA agent, that agent has to be clinically significantly superior to placebo. But as a physician in the office, I just need to make the patient feel better, regardless of how much of that effect is from the placebo.”

‘You need to keep the placebo in mind if you’re going to evaluate new treatments.’ —Dr. Block

Platelet-rich plasma has some evidence suggesting it is effective, but it is not strong evidence, Dr. Block said. “We assume it’s safe, but we also know there’s no compelling reason why anybody would report adverse events,” he said.

He said “absolutely no evidence” exists that platelet-rich plasma has a structural effect in OA, but there is at least some encouraging data on pain relief. The systematic reviews on platelet-rich plasma and pain relief “tend to be positive. The more honest ones conclude that although it appears to be better, the level of evidence is limited due to the high risk of bias across the trials. And I think that’s the fairest conclusion.”

He cautioned that “whenever you’re looking at meta-analyses, you need to be wary of topics for which the data are sparse.” That said, many people feel relief after PRA, “probably due to the placebo effect, because we know it probably doesn’t matter which protocol is used.”

Interest in stem cell therapy has grown in the hopes it can spark structural recovery, but the evidence has not been encouraging, Dr. Block said.2 “Individual patients appear to feel benefit, often with prolonged duration,” which is possibly due to a placebo effect, he said. “There is no good evidence of a specific pain advantage. There is no good evidence of a structural advantage.”

The same holds true for prolotherapy, in which small volumes of crystalloid are injected with the intention of stimulating a healing process. It has been around since the 1950s and appears to be relatively safe, Dr. Block said.3 “But the data are not available to evaluate systematically,” he said. “There is no evidence of a structural benefit.”

All the above leaves a gaping void in OA pain treatment, Dr. Block said. “OA pain represents an enormous unmet need,” he said. “People really want to believe in breakthroughs and options, especially if they are natural. Be wary of dramatic results.”

Thomas R. Collins is a freelance writer living in South Florida.

References

- Zou K, Wong J, Abdullah N, et al. Examination of overall treatment effect and the proportion attributable to contextual effect in osteoarthritis: Meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. Ann Rheum Dis. 2016 Nov;75(11):1964–1970.

- Piuzzi NS, Ng M, Chughtai M, et al. The stem-cell market for the treatment of knee osteoarthritis: A patient perspective. J Knee Surg. 2017 Jul 24.

- Krstičević M, Jerić M, Došenović S, et al. Proliferative injection therapy for osteoarthritis: A systematic review. Int Orthop. 2017 Apr;41(4):671–679.