Editor’s note: ACR on Air, the official podcast of the ACR, dives into topics important to the rheumatology community, such as the latest research, solutions for practice management issues, legislative policies, patient care and more. Twice a month, host Jonathan Hausmann, MD, a pediatric and adult rheumatologist in Boston, interviews healthcare professionals and clinicians on the rheumatology front lines. In a series for The Rheumatologist, we provide highlights from these relevant conversations. Listen to the podcast online, or download and subscribe to ACR on Air wherever you get your podcasts. Here we highlight episode 55, “Macrophage Activation Syndrome,” which aired on June 6, 2023.

Editor’s note: ACR on Air, the official podcast of the ACR, dives into topics important to the rheumatology community, such as the latest research, solutions for practice management issues, legislative policies, patient care and more. Twice a month, host Jonathan Hausmann, MD, a pediatric and adult rheumatologist in Boston, interviews healthcare professionals and clinicians on the rheumatology front lines. In a series for The Rheumatologist, we provide highlights from these relevant conversations. Listen to the podcast online, or download and subscribe to ACR on Air wherever you get your podcasts. Here we highlight episode 55, “Macrophage Activation Syndrome,” which aired on June 6, 2023.

Macrophage activation syndrome (MAS) needs swift treatment, unlike many other rheumatic conditions that require more long-term, but non-emergent, management. Diagnosing and managing MAS often takes collaboration with colleagues from other specialties, as well as consensus building, said Lauren Henderson, MD, MMS, an assistant professor of pediatrics at Harvard Medical School, Boston, and an attending pediatric rheumatologist at Boston Children’s Hospital. Dr. Henderson specializes in treating children with complex autoimmune diseases and has led local and national efforts to improve the diagnosis and management of patients with MAS and other hyperinflammatory syndromes.

Dr. Henderson

In her conversation with Dr. Hausmann on ACR on Air, Dr. Henderson addressed the challenges of identifying and diagnosing MAS and achieving a consensus on how to treat it.

What’s in a Name?

One issue with MAS is its nomenclature because the same phenomenon has a different name in other specialties. “The field has a bit of a mess on its hand [because] the names we use are confusing,” said Dr. Henderson.

Rheumatologists manage and tend to call the condition MAS; however, it has also been referred to as hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis (HLH).

This naming confusion may have led to different perspectives on the condition because rheumatologists treat MAS in patients with systemic juvenile idiopathic arthritis (sJIA), while oncologists treat the condition in patients with malignancy, Dr. Hausmann says.

Ultimately, Dr. Henderson likes to think of MAS as a final common pathway that results from many different potential insults—be it genetic, a bad infection, cancer, autoimmune disease or something else.

“You can have a rheumatologic condition, and for some reason, your immune system gets extra activated. It produces a lot of cytokines, and there’s a lot of activation with macrophages and T cells, and you can get this final common pathology [in which] there’s too much inflammation. The inflammation your body is making is actually the problem—not the original insult,” she said.

Collaboration

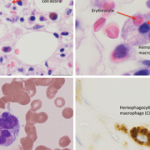

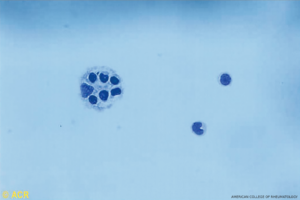

A papanicolaou stain of the cerebrospinal fluid from an 8-year-old child. A diagnosis of

MAS was confirmed by the presence of active macrophage ingestion of hematopoietic cells in the bone marrow and cerebrospinal fluid. (Click to enlarge.)

Dr. Henderson shared how she became interested in MAS, explaining that when she was a resident, some patients were very sick from hyperinflammation. Rheumatologists and hematologists would have different names for what was happening and couldn’t completely agree on what to do for the patients.

“They were used to managing this condition very separately—different medicines, different approaches,” she said.

Example: Hematologists and oncologists would have clear protocols for when these patients would get a chemotherapy drug, such as etoposide, but would not start treatment right away. Rheumatologists would have drugs to intervene, such as glucocorticoids and cytokine inhibitors, but would end up in disagreement over treating the condition early with some of these medications or waiting until a child got sicker and using etoposide.

“As a resident, [I] felt pretty terrible when [we had] a very sick child and the teams [couldn’t] agree on what to do, but something needed to be done fast. That would often leave teams upset and parents confused,” she said.

That situation inspired Dr. Henderson’s interest in how to address the problem and led to the formation of multidisciplinary teams at Boston Children’s Hospital to come up with a consensus on how to treat patients with HLH and MAS using evidence-based guidelines.

“In the end, we basically got everyone in a room once a month for eight or nine months and talked about what our plan was going to be,” she says. At that point, there was existing evidence from the hematology and oncology group involving large chemotherapy trials, but less evidence from the rheumatology side on using medications, such as steroids and anakinra, for MAS/HLH.

“I think, in the end, what we learned is that oncologists don’t want to give chemotherapy for HLH if they can avoid it. The rheumatologists had something to offer first level, which would be steroids and biologics or Janus kinase [JAK] inhibitors that are less toxic,” she said.

The clinicians liked this solution because it often gave the patient an intervention quickly that wasn’t as toxic as chemotherapy.

Rheumatologists at other institutions who want to have a consensus on how to treat MAS can work with others within their institution to discuss and agree on how to manage it. Buy-in from the institution itself is crucial for this approach, Dr. Henderson said.

Identifying MAS

Dr. Hausmann asked about training staff to identify MAS in patients. This diagnosis can be challenging because it may seem as if the patient has a bad infection or a malignancy.

At Dr. Henderson’s hospital, staff members have experience with sJIA. Therefore, they know to be suspicious if a child comes in with a high fever and longer-term inflammation. Staff members will conduct a ferritin test to help identify potential MAS.

“[The patient is] sick enough with fever to be admitted to the hospital, and the cause isn’t clear, and you’re starting to see a lot of organ dysfunction,” Dr. Henderson said.

Other clues can be a falling complete blood count, high inflammatory markers, such as C-reactive protein, a falling erythrocyte sedimentation rate and a high ferritin level. On exam, a patient with sJIA may also have a rash and large lymph nodes.

Other tests can be conducted, such as CXCL9 to check for interferon gamma signaling and a test to check for interleukin 18. However, because it may take days or weeks to get these test results, rheumatologists and other clinicians have to drill down to find the inciting trigger quickly, Dr. Henderson aid. This approach may mean calling an infectious disease specialist to rule out mononucleosis, Epstein-Barr virus or other infections. It can also mean working with hematologists and oncologists to rule out such conditions as T cell lymphoma and an immunologist to check for immune problems.

“Sometimes, interventions need to be started while the diagnostic workup is ongoing,” Dr. Henderson said.

MAS Treatment

Dr. Henderson shared the typical treatment used for a patient in a full-blown MAS/HLH cytokine storm, which usually includes a high dose of glucocorticoids, along with a cytokine inhibitor. This treatment usually starts with anakinra. If that doesn’t lead to a quick response in a patient, she and her team may use other cytokine inhibitors, as well as JAK inhibitors or emapalumab that block interferon gamma signaling. If those medications are not helping, the team stays in close contact with hematology and oncology in case they need to give a patient chemotherapy.

Vanessa Caceres is a medical writer in Bradenton, Fla.

More Episodes

A new episode of ACR on Air comes out twice a month. Listen to this full episode and others online at acronair.org. Or download and subscribe wherever you get your podcasts.