On May 1, after their annual scientific meeting in Chicago, the American Geriatrics Society Panel on the Pharmacological Management of Persistent Pain in Older Persons updated its guidelines for this patient population.1,2 One of the primary changes is a move away from using nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), either cyclooxygenase-2 inhibitors or traditional NSAIDs. The original guidelines, published in 2002, recommended that older patients use any NSAIDs (e.g., prescription or over the counter [OTC]) rather than opioids for persistent pain.3 This updated guideline notes a greater risk (e.g., cardiovascular, renal, gastrointestinal [GI]) for using NSAIDs in this patient population. Using newer clinical trial data and data from clinical observations, the panel now recommends that NSAIDs be rarely considered in highly selected older individuals. When they are considered for use, it should be with extreme caution. For these individuals, the guideline recommends using GI protection with a proton pump inhibitor (PPI) or misoprostol, not taking more than one NSAID for pain relief at a time, and routinely assessing for GI and renal toxicity, hypertension, heart failure, and other drug–drug and drug–disease interactions.

Additionally, patients taking aspirin for cardioprophylaxis should not use ibuprofen.

The guidelines recommend using opioids for older patients with moderate to severe pain or pain-induced diminished quality of life, noting that opioids may be potentially safer for long-term use than NSAIDs. The guidelines also recommend using adjuvant therapies for managing refractory pain. For example, the panel recommends avoiding tertiary tricyclic antidepressants (e.g., imipramine, doxepin, amitriptyline) because of a higher risk for anticholinergic and cognitive adverse effects.4 Avoiding the use of tertiary tricyclic antidepressants is relatively consistent with the updated Beers criteria for potentially inappropriate medication use in older patients.5 Additionally, it is imperative to assess bowel function initially and at follow-up in all opioid-treated patients, as constipation and other GI symptoms may occur.3 It is usually appropriate to prescribe a prophylactic bowel regimen for patients who will be on persistent opioid therapy. Physicians should also encourage adequate fluid intake.

To ensure that patients are aware of the risks and benefits of using mycophenolate mofetil (MMF; CellCept, Myfortic, and generics), Roche and the FDA developed a medication guide that now accompanies every prescription filled for MMF-containing products. One risk includes the possibility of developing of progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy (PML) (see below).6

New Approvals

- Certolizumab pegol (Cimzia) was approved by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for treating moderately to severely active rheumatoid arthritis (RA). Dosed subcutaneously as an initial injection of 400 mg, with 400-mg injections subsequently at two and four weeks, further injections of 200 mg should be administered every other week. Maintenance therapy includes dosing at 400 mg every four weeks. In clinical trials, certolizumab pegol with MTX reduced signs and symptoms of RA at 24 weeks compared with MTX monotherapy.14

- Lansoprazole (Prevacid 24 hours) received FDA approval for OTC use to treat frequent heartburn. It is the second PPI to gain OTC status and should be available later this year.15

Label Changes and Warnings

In May, the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) requested that the manufacturers of all anti-epileptic drugs (AEDs) include a warning in the label of this class of these agents regarding an increased risk of suicidal thoughts and suicidal ideation. Each company will develop a medication guide that explains the risks to patients and that will accompany all filled prescriptions of these drugs (except agents indicated for short-term use). Medication guide updates are expected to be completed by year’s end. It is important for the rheumatology community to be aware of this because patients may have questions about use of these agents and associated risks.

The list of affected drugs includes: carbamazepine (Carbatrol, Equetro, Tegretol, Tegretol XR); clonazepam (Klonopin); clorazepate (Tranxene); divalproex sodium (Depakote, Depakote ER, Depakene); ethosuximide (Zarontin); ethotoin (Peganone); felbamate (Felbatol); gabapentin (Neurontin); lamotrigine (Lamictal); levetiracetam (Keppra, Keppra XR); methsuximide (Celontin); oxcarbazepine (Trileptal); phenytoin (Dilantin Suspension); pregabalin (Lyrica); primidone (Mysoline); tiagabine (Gabitril); topiramate (Topamax); trimethadione (Tridione); valproic acid (Stavzor);and zonisamide (Zonegran).

Many AEDs are used on- or off-label to treat pain syndromes.7 All patients using or starting an AED for any indication should be monitored for notable changes in behavior that could indicate the emergence or worsening of suicidal thoughts, suicidal behavior, or depression. If suicidal thoughts or behaviors emerge during AED treatment, the prescriber should consider whether these symptoms may be related to the illness being treated and act accordingly.

PML with Biologic Therapy in RA

Since the FDA’s removal of efalizumab from the U.S. market, does the rheumatology community still need to worry about PML? In a word, yes. There have been cases of PML, a rare but often fatal opportunistic infection in patients treated with rituximab. The FDA added a boxed warning and updated warning information on the label, noting patients with autoimmune diseases that developed PML had prior or concurrent immunosuppressive therapy. The label also states that PML developed within 12 months of the last rituximab infusion.8

Although natalizumab is not approved for treating rheumatologic conditions, it is used to treat inflammatory bowel disease and multiple sclerosis. With natalizumab in its infancy as a biologic agent for treating immune-mediated diseases, cases of PML began to emerge. The development of these cases prompted the FDA to remove it from the market. It was later re-introduced with prescribing restrictions.9,10

As noted earlier in this article, there has been some concern with MMF and the development of PML. There have been PML cases, sometimes fatal, reported in patients treated with MMF. Because MMF also is used to manage RA patients, it is important to consider PML in the differential diagnosis of a patient that presents with new neurological symptoms, including but not limited to hemiparesis, apathy, confusion, cognitive deficiencies, and ataxia. In the potentially MMF-induced PML cases, patients had PML risk factors, including treatment with immunosuppressive therapies and impaired immune function. In patients presenting with suspect neurologic findings, a consultation with a neurologist should occur as clinically indicated. Physicians should also consider reducing the amount of immunosuppression in patients who develop PML.6

Pipeline

Tocilizumab (Actemra), an anti–interleukin-6 receptor antibody already approved abroad, is pending at the FDA.16 In March, Chugai reported 15 deaths in Japanese patients that used tocilizumab; however, causality was not determined. All of these patients had RA and were treated with tocilizumab. Additionally, interim study results note that in 4,915 patients who have used tocilizumab, pneumonia and severe fever have occurred in more than 200 patients.17

Have there been reports of PML in patients treated with tumor necrosis–a antagonists? According to Furst, there have been unconfirmed reports documenting PML associated with both etanercept and infliximab therapy.11 In addition, there was a case reported in a patient with refractory RA who was treated with etanercept.12 In this case, an elderly woman had failed many therapies for RA, including prednisolone, auranofin, penicillamine, methotrexate (MTX), leflunomide, cyclophosphamide, and others. She also received daily isoniazid (INH) due to a possible history of tuberculosis. She ultimately received etanercept 25 mg twice weekly with rapid symptom resolution. During the subsequent month, the INH was changed to rifampin, and the etanercept was continued. Five months later, she was admitted to the hospital for severe malaise and appetite loss with subsequent incontinence, a gradual decline in her ability to communicate, and dementia. Eventually she developed seizures and loss of consciousness.

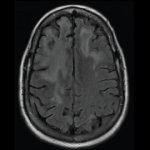

Upon work-up, the patient had neck rigidity, and the cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) showed an elevated protein concentration of 84 mg/dL (normal, 10–40 mg/dL) and a cell count of 30/3 mL (normal, 0/3–10/3 mL). An MRI showed high-intensity lesions disseminated bilaterally throughout the white matter. The patient was initially inaccurately diagnosed and treated for encephalomeningitis. After consulting with a neurologist, she was clinically diagnosed with PML. Attempts to detect JC virus via polymerase chain reaction (PCR) were unsuccessful, leading to two negative results. The patient generally stayed in bed, but with supportive treatment she improved enough to sit up to have meals. She was subsequently transferred to another facility to undergo rehabilitation. The authors noted that PML can be diagnosed by examining the CSF and by evaluating clinical symptoms. Examining MRI scans is also useful. The sensitivity of JC virus-DNA PCR in CSF is reported to be approximately 74% to 92%. The authors also noted that this patient had most of the PML features minus the JC virus in the CSF.

Calabrese and Molloy reported that vigilance is warranted in the rheumatology community when it comes to recognizing and pursuing a diagnosis of PML, especially when it is suspected via identifying clinical signs and symptoms and MRI findings.13 Rheumatologists need to know about PML, be aware of its symptoms, be able to assist patients in making informed treatment decisions, and educate them about the risks and benefits of immunosuppressive therapies.

Michele Kaufman is a freelance medical writer based in New York City.

References

- AGS Panel on Pharmacological Management of Persistent Pain in Older Persons. AGS Clinical Practice Guideline: Pharmacological Management of Persistent Pain in Older Persons Executive Summary. American Geriatrics Society. www.americangeriatrics.org/education/executive_summary.shtml. Published April 21, 2009. Accessed June 3, 2009.

- American Geriatrics Society announces new guidelines to improve pain management, quality of life, and quality of care for older patients. American Geriatrics Society. www.americangeriatrics.org/news/pain043009.shtml. Published May 1, 2009. Accessed June 3, 2009.

- AGS Panel on Persistent Pain in Older Patients. The management of persistent pain in older patients. JAGS. 2002;50:S205-S224.

- AGS Panel on Pharmacological Management of Persistent Pain in Older Persons. Pharmacological Management of Persistent Pain in Older Persons. American Geriatrics Society. www.americangeriatrics.org/education/final_recommendations.pdf. Published April 2009. Accessed June 3, 2009.

- Fick DM, Cooper JW, Wade WE, Waller JL, Maclean R, Beers MH. Updating the Beers criteria for potentially inappropriate medication use in older adults—results of a US consensus panel of experts. Arch Intern Med. 2003;163:2716-2724.

- New CellCept (mycophenolate mofetil) medication guide to be distributed by pharmacists. Food and Drug Administration. www.fda.gov/downloads/Safety/MedWatch/SafetyInformation/SafetyAlertsforHumanMedicalProducts/ucm093666.pdf. Published January 2009. Accessed June 3, 2009.

- Suicidal behavior and ideation and antiepileptic drugs. Food and Drug Administration. www.fda.gov/cder/drug/infopage/antiepileptics. Published May 5, 2009. Accessed June 3, 2009.

- Highlights of prescribing information: Rituxan. Genentech. www.gene.com/gene/products/information/pdf/rituxan-prescribing.pdf. Published September 2008. Accessed June 3, 2009.

- Waknine Y. Tysabri suspended from US market. Medscape. www.medscape.com/viewarticle/500466. Published February 28, 2006. Accessed June 3, 2009.

- Richwine L. Tysabri approved for treatment of Crohn’s disease, with restrictions. Medscape. www.medscape.com/viewarticle/568830. Published January 15, 2008. Accessed June 3, 2009.

- Furst DE. The risk of infections with biologic therapies for rheumatoid arthritis. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 2008 Dec 29 (Epub ahead of print).

- Yamamoto M, Takahashi H, Wakasugi H, et al. Leukoencephalopathy during administration of etanercept for refractory rheumatoid arthritis. Mod Rheumatol. 2007;17:72-74.

- Calabrese LH, Molloy ES. Progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy in the rheumatic diseases: Assessing the risks of biologic immunosuppressive therapies. Ann Rheum Dis. 2008;67(Suppl III):iii64-iii65.

- UCB’s CIMZIA (certolizumab pegol) approved by the U.S. FDA for adult patients suffering from moderate to severe rheumatoid arthritis. UCB. www.ucb.com/news/newsdetail?det=1314787 Published May 14, 2009. Accessed June 3, 2009.

- Hitti M. Heartburn drug Prevacid goes over the counter. Web MD. www.webmd.com/heartburn-gerd/news/20090514/heartburn-drug-prevacid-goes-over-the-counter. Published May 14, 2009. Accessed June 3, 2009.

- Chugai shares fall after deaths among Actemra users. Reuters. www.reuters.com/article/rbssHealthcareNews/idUST37022720090318. Published March 18, 2009. Accessed June 3, 2009.

- Takahashi Y, Maxwell K. Roche partner discloses drug dangers. Wall Street Journal. http://online.wsj.com/article/SB123735013931766981.html. Published March 19, 2009. Accessed June 3, 2009.