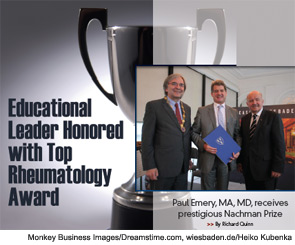

The third time was a charm for Paul Emery, MA, MD. Dr. Emery, Arthritis Research Campaign Professor of Rheumatology at Leeds University, England, is the 2012 winner of the prestigious Carol Nachman Prize for Rheumatology. He is only the second British rheumatologist to earn the distinction since the award was first given in 1993. The prior winners were professors Ravinder N. Maini and Marc Feldmann, who split the award in 1999.

Dr. Emery heads the division of rheumatic and musculoskeletal disease at the Leeds Institute of Molecular Medicine and is director of the Leeds Musculoskeletal Biomedical Research Unit at Leeds Teaching Hospitals Trust. He is past president of the European League Against Rheumatism (EULAR) after serving as president for 2009–2011. His other distinctions include serving as the inaugural president of the International Society for Musculoskeletal Imaging in Rheumatology and receiving the 2002 EULAR prize for rheumatologic research. Dr. Emery, who has published more than 800 peer-reviewed articles, focuses his research on the immunopathogenesis and immunotherapy of rheumatoid arthritis, ankylosing spondylitis, and connective tissue diseases. He recently spoke with The Rheumatologist to discuss the Nachman Prize.

The Rheumatologist: What does an award like this mean to you?

Dr. Paul Emery: It is very important. It is an international prize and the highest prize specifically for rheumatology. It is only the second time it has gone to the U.K. in the last 20 years. It is external recognition over a long period of work, providing an objective assessment of one’s achievement.

TR: In a specialty as small as rheumatology, how important are awards like this not only to the winners, but their colleagues, support staff, and institutions?

PE: It is particularly important in rheumatology because much of the cutting-edge work is done at an early stage of disease. To see patients at this time requires an army of people to organize efficiently. Therefore, there is a large number of people doing a large amount of work, and this is recognized by the Carol Nachman award.

TR: As an educator, you see residents succeed because of processes that you’ve put in place. How satisfying is that to see they then go on to create their own initiatives?

PE: I think it is very satisfying to see trainees develop into leaders of their specialties. If they do that, then that’s a very great thing for them. For their trainers, it is crucial to spot the abilities of trainees and give them the environment in which to thrive.

TR: What evolution have you seen in training over the course of your career?

PE: I have seen only improvement in education. It is much more organized, and the CME is now very good. We have large numbers of trainees with educational training sessions every week. The one downside for trainees, educationally speaking, is that they spend far less time on call and therefore see less clinical material than in the past, but the education is much more structured. We learned on our feet, but these days there is much more to learn and it is organized much better.

TR: The work-hours issue looms large in the U.S. Is that as big an issue in the U.K.? What’s your view on the situation?

PE: Longer hours are very good for learning medicine, especially acutely, but not so good at a personal level. I think you learn a huge amount by doing it, which shapes your career. Inevitably it is a compromise, and some people in the past were not able to cope with that level of sustained work.

From a U.K. perspective, there is the choice of training in either monospecialty rheumatology or dual-specialty training in internal medicine and rheumatology. To do internal medicine well in addition to rheumatology, you do really need to do more on call than it is currently possible to do with the European Directive, which limits your hours officially to 48.

TR: Physicians get into medicine to help people. How satisfying is a specialty where you can, as you say, cure and be able to see that this actually worked, as opposed to others where more positive lifelong outcomes aren’t always obtainable?

PE: It is one of the reasons—it was the main reason—I did rheumatology, because I experienced it very early in my career and then went back to rheumatology and saw the same patients. It’s enormously satisfying to look after patients whom you know well. This is very different from the surgeons who perhaps see their patients once or twice, or even cardiologists who see them fairly rarely. Rheumatologists actually get to know their patients well.

Richard Quinn is a freelance writer based in New Jersey.