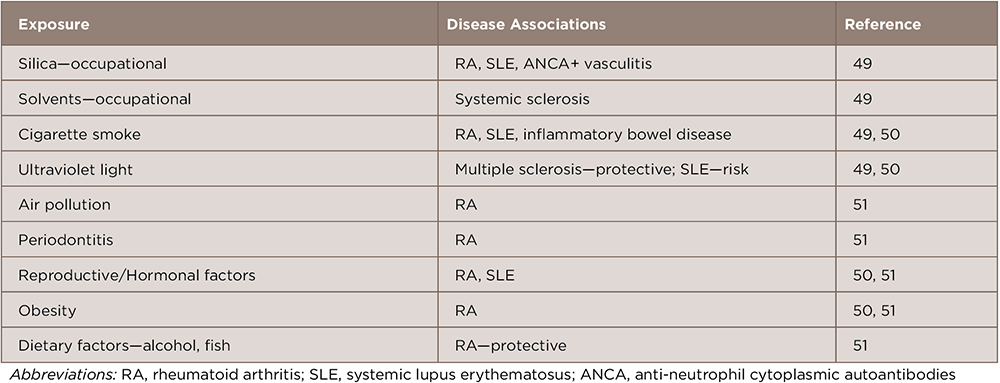

Systemic autoimmune diseases are thought to result from immune dysregulation in genetically susceptible individuals who were exposed to environmental risk factors. Many studies have identified genetic risk factors for these diseases, but concordance rates among monozygotic twins are 25–40%, suggesting that nonheritable environmental factors play a more prominent role.1,2 Through carefully conducted epidemiologic and other approaches, environmental factors for adult forms of these diseases have been identified (see Table 1).

Here we review emerging data for pediatric systemic autoimmune diseases, particularly juvenile idiopathic arthritis (JIA). Although most studies have been conducted in JIA, we also include data for pediatric systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE), juvenile dermatomyositis (JDM) and Kawasaki disease, a systemic vasculitis in young children. Our focus is primarily on case-control studies, including those that compare subgroups to identify severity factors.

Seasonality & Temporal & Spatial Clustering

Variations in the onset of disease suggest that seasonal environmental factors may be involved in the etiology. Seasonal variations in birth distribution suggest that seasonal neonatal or perinatal exposures may have a role in the development of disease. Several studies of systemic autoimmune diseases in children found seasonal variation in disease onset or in birth distributions.

Although a study of systemic JIA found no seasonality in disease onset in Canada during a 12-year period, there was a seasonal pattern in onset in the Prairie region, with peaks in the fall and early spring, but these peaks did not correlate with viral or Mycoplasma pneumoniae seasonal outbreaks in that region.3 A large study of JIA in Israel showed seasonality in birth dates, with a peak from November to March and nadir in the summer months compared with the general population, but a Danish national study of JIA found no birth seasonality and no temporal or spatial clustering of cases.4,5

In juvenile myositis, there was no overall seasonality to birth dates in a national study population, but subgroups of patients had seasonal birth distributions, including Hispanic patients, who had a peak birth seasonality in mid-October, and anti-p155/140 autoantibody negative JDM patients, who had a peak birth seasonality in July.6

(click for larger image)

Table 1: Possible Environmental Risk Factors for Systemic Autoimmune Diseases in Adults

A global analysis of Kawasaki disease using data from 25 countries over three decades demonstrated peak disease onset in the winter months, January through March, in the northern hemispheres, with a nadir in August and September.7 Active surveillance of Kawasaki disease cases in a five-year period in San Diego County, Calif., demonstrated significant clustering of cases within a space–time interval of 3 kilometers and three to five days, suggesting a potential infectious or other environmental trigger operating within a relatively small geospatial window.8

Further analysis of the seasonality of Kawasaki disease and associated epidemics in Japan, Hawaii and San Diego suggests a relationship between seasonal and epidemic peaks and wind currents originating from central Asia and traveling through the North Pacific, with a very short lag time to disease onset, based on the temporal and spatial distribution of cases.9,10 The authors hypothesized a role for a windborne pathogen, such as a mycobacteria or a noninfectious toxin.

Infection & the Microbiome

Various infectious agents have been suggested to be a trigger for JIA, but few controlled studies exist (reviewed in references 11–13). Cyclical variations in the incidence of JIA in Manitoba, Canada, with three- to five-year peaks in the cycles, correlated with concomitant increases in Mycoplasma pneuomoniae infections.14 Parvovirus B19 has been associated with JIA, with an increased frequency of immunoglobulin (Ig) M and IgG antibodies against the organism and viral DNA in the serum and synovial fluid in JIA patients, compared with controls, but other studies have not confirmed this association.15,16

The role of infection early in life and increased exposure to infectious agents via larger family size, urban dwelling or contact with animals is part of the hygiene hypothesis, which posits that increased exposure to infection early in life may be protective for the development of autoimmune disease.13

Some well-designed studies do not support the hygiene hypothesis in JIA, however, with several large case-control studies based on medical record review and use of registry data concluding that an increase in early-life infections and antibiotic usage are risk factors for JIA.

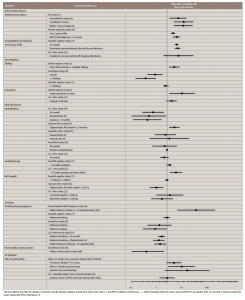

A large case-control study of electronic medical records from more than 550 general pediatric practices in the U.K. showed that antibiotic exposure is associated with development of JIA. They found that a higher risk of JIA was associated with more courses of antibiotic use, with the strongest effect within 12 months of diagnosis, even when adjusting for the number and type of infections (see Table 2). These findings suggest a potential role for bacterial infection or for an alteration of the microbiome in disease development.17

(click for larger image)

Table 2: Possible Environmental Risk Factors Associated with Juvenile Idiopathic Arthritis (JIA)*

*All associations are with JIA, except as noted for specific disease subtype. Forest plots show odds ratio ( • ) and 95% confidence interval (CI, — ). Risk is elevated when the mean value and 95% CI are greater than 1.0, and risk is reduced when the mean values and 95% CI lie below 1.0.

A role for antibiotic usage, particularly in the first two years of life, but up to the date of diagnosis with JIA, was also observed in a Finnish national registry case-control study based on antibiotic prescription reimbursement records. The study also found a higher risk of JIA was associated with more courses of antibiotic use and with certain antibiotics, including lincosamides and cephalosporins.18 An altered fecal microbiome, including a reduction in Firmicutes and increase in Bacteroides species, was reported at diagnosis in the stool samples of children with JIA compared with healthy control children.19

A recent study of children with JIA and anti-CCP autoantibodies found they were more likely to have tender/bleeding gums on oral health history and higher antibody titers to Porphyromonas (P.) gingivalis and P. intermedia, suggesting a role for periodontitis and the oral microbiome in a subgroup of patients with JIA.20

A large case-control Swedish registry found an association between a higher risk for JIA and the number of hospitalizations for infection in the first year of life, including for respiratory, gastrointestinal or skin/soft-tissue infections21 (see Table 2). However, a smaller U.S. playmate-matched case-control questionnaire study did not find this association with hospitalization for infection in the first year of life, nor with attendance at daycare for those younger than 6 years of age.22

Several analyses of demographic factors suggest smaller (vs. larger) family size and urban environments are modifiers of JIA risk, but the data are mixed. A higher risk of JIA was associated with being a single child in a family and with higher parental income in a national Danish case-control study of incident JIA cases, which used socioeconomic registry data to extract demographic and socioeconomic factors (see Table 2, Demographics).5

Having any siblings, particularly three or more siblings, was protective for JIA risk in an Australian case-hospital control questionnaire study.23 No effect of sibling number was reported in the Swedish case-control registry study or birth order in the Seattle case-control study.21,22 These first two studies are consistent with the hygiene hypothesis, but the latter two are not.

The Danish national registry case-control study found a higher risk of JIA with urban dwelling compared with living on a farm (see Table 2, Demographics).5 However, the Seattle case-control study did not find an association with rural residence or with the frequency or type of household pets.22

A German case-hospital control questionnaire study saw no effect of living in an urban vs. rural area, living on a farm in the first year of life or exposure to farm animals or pets during infancy on development of oligoarticular JIA.25

In other pediatric systemic autoimmune diseases, however, including JDM, pediatric SLE and Kawasaki disease, a variety of infections have been temporally associated with disease onset (reviewed in reference 26), but few case-control studies have corroborated these. A case-control epidemiologic study of 80 newly diagnosed cases compared JDM with JIA and healthy controls and reported a greater number of infectious illnesses antecedent to diagnosis in JDM patients, based on structured interviews.27

In a five-year U.S. registry study of 286 incident JDM patients, children younger than 6 years of age more frequently had respiratory symptoms within three months of disease onset than older children, based on responses in questionnaires and structured interviews. JDM patients with constitutional or gastrointestinal symptoms at diagnosis were also more likely to have contact with sick animals prior to diagnosis.28

A second U.S. juvenile myositis registry study, using physician questionnaire and medical record review, found differences in exposures by subgroup, with more frequent antecedent infections in older children and those who did not have myositis autoantibodies.29 Another study using this same registry also found antecedent infections within six months of illness onset to be associated with a chronic or polycyclic course of illness.30

Some studies have utilized biospecimens to assess exposure to infectious organisms. However, a case-control study of recent-onset JDM vs. matched healthy controls found no difference in the detection of parvovirus antibodies or DNA in the peripheral blood or muscle tissue.31 In studies of newly diagnosed JDM patients, antibody titers to coxsackievirus B, herpes simplex virus or Toxoplasma gondii did not differ compared with controls, and no enteroviral RNA or bacterial DNA was detected in the affected muscle tissue from 20 JDM patients.27,32 In pediatric SLE, a small case-control study detected uniform seroreactivity to EBNA-1, an Epstein-Barr virus–associated nuclear protein, in SLE patients, but not as frequently in healthy controls.33

Early Life Factors

The role of early life factors has been examined in several case-control studies (see Table 2, Early Life Factors). The effects of breastfeeding, as ascertained by questionnaire data, on the development of JIA are unclear, but breastfeeding may decrease risk and severity. One U.S. case-control study found that longer breastfeeding (for more than three months) was protective against the development of JIA, particularly in the pauciarticular subgroup,34 but a German study suggested increased risk of JIA with breastfeeding,25 and three other case-control studies showed no effect (see Table 2, Breastfeeding).22,35,36

A longitudinal cohort study of healthy children found that breastfeeding for more than three months is protective against the development of rheumatoid factor in those without the RA susceptibility factor, HLA-DR-4.37

A large, prospective, U.K. multicenter study reported that breastfeeding was associated with younger age at onset of JIA, as well as with lower disease activity, pain and functional disability scores at diagnosis.38

The larger Swedish registry case-control study based on medical records found that prolonged gestation (longer than 42 weeks) was associated with increased risk of JIA,21 whereas a U.S. hospital case-control questionnaire study found premature birth to be associated with increased JIA risk.22

Low birth weight was protective against the development of oligoarticular JIA in the German case-control questionnaire study,25 but no effect of birth weight on JIA risk was observed in the Swedish registries or in two Washington state case-control studies, one based on birth certificate records and one a clinic-based questionnaire study (see Table 2, Birth weight).21,22 No effect of mode of delivery was seen in these studies.

In a small Brazilian case-control study based on questionnaire data, maternal occupational exposure to chalk dust or gasoline vapor was associated with JDM.39

Smoking

Because smoking is less frequent in children than adults, studies examined parental smoking during pregnancy and passive smoke exposure in the home. Studies of maternal smoking during pregnancy suggest mixed effects (see Table 2, Smoking).

The Finnish Medical Birth Registry study showed that maternal smoking was associated with a higher risk of JIA in girls, with greater risk among girls whose mothers were heavy smokers (more than 10 cigarettes per day).40 In contrast, no effect of maternal smoking on risk of JIA was seen in the Swedish inpatient registry case-control study based on maternal birth registry records.21

JIA was associated with lower levels of maternal prenatal smoking compared with controls, and this effect was more pronounced among patients in the oligoarticular/extended oligoarticular JIA subgroups in a Washington state case-control study based on case identification through ICD-9 coding and examination of birth certificates. Although the analysis was adjusted for confounders, residual differences in socioeconomic status or differential reporting may have contributed to those effects.24

Maternal smoking during pregnancy was also found to be an independent risk factor for JDM in a small Brazilian case-control questionnaire study.39

The effects of exposure to passive smoking in childhood may also affect JIA. One disease-comparison study showed a higher prevalence of JIA compared with other chronic diseases in children exposed to daily passive tobacco smoke.41 By contrast, the Australian case-control study found a protective effect of paternal indoor smoking, which they speculated could be due to cessation of smoking with onset of disease symptoms (see Table 2, Smoking).36

Air Pollution

Several studies examined the effects of air pollution on the development of pediatric systemic autoimmune diseases. In a study in Utah, higher concentrations of fine air particulate matter (42

In a follow-up study spanning more than a decade, Zeft et al examined short-term exposure to small particulate matter (PM2.5) based on central daily air monitoring in a case-crossover design in 250 patients living in five metropolitan areas in the U.S. and Canada. No significant associations between PM2.5 concentrations and risk of systemic JIA were observed; however, a trend toward higher risk in younger children (younger than 5.5 years old) was again observed, but was not significant.43

In other systemic autoimmune diseases, a case-control study of pregnancy exposures found that the highest tertile of carbon monoxide exposure during the third trimester of pregnancy, based on daily air pollution monitoring stations located throughout the city of São Paulo, Brazil, was a risk factor for JDM.39 However, in a multicenter North American clinics cohort of more than 3,000 patients, there was no increased risk of Kawasaki disease associated with short-term PM2.5 air particulate exposure based on daily central monitoring of seven metropolitan cities.44

Two Brazilian studies found effects of air pollution on the disease activity of systemic autoimmune diseases. One study examined the effect of air pollutants, as measured by local monitoring stations, on the fluctuation of hospital admissions of pediatric systemic rheumatic diseases, including JIA, JDM, lupus, vasculitides and systemic sclerosis. That study found a weak, but significant, relationship between sulfur dioxide and increased hospital admissions 14–17 days after exposure was detected. No relationship was found with other air pollutants, such as PM10, ozone, nitrogen peroxide and carbon monoxide.45 In a second study, air pollutants, including carbon monoxide, nitrogen dioxide and PM10, were associated with higher activity in pediatric lupus, as measured by SLE Disease Activity Index scores >8, approximately two weeks after exposure.46

Other Factors

Breastfeeding may decrease the risk and severity of JIA.

A higher frequency of psychosocial stressors at symptom onset or experienced at the time of diagnosis has been reported in patients with JIA vs. healthy controls. Stressors included parental separation, an ill family member and problems getting along with others.47 Exposure to high levels of ultraviolet radiation in the month before symptom onset based on residential location was associated with higher odds of having JDM compared to juvenile polymyositis (which lacks the characteristic skin rashes) and with the anti-p155/140 (TIF-1) myositis autoantibody (an autoantibody group more associated with photosensitive skin rashes).48

Conclusions

Although the field is in its infancy and conflicting results exist, current studies suggest that several environmental factors affect the risk of JIA and other systemic pediatric autoimmune diseases. Well-conducted and sufficiently powered investigations have found a role for early life infections and antimicrobial use as risk factors for JIA, which challenge the hygiene hypothesis. Premature or post-term birth, fewer siblings in the family, maternal smoking during pregnancy and air pollution are possible risk factors for JIA, but they need confirmation and further examination of JIA subtypes.

Studies in other pediatric autoimmune diseases are smaller, with antecedent infection and short-term exposure to ultraviolet radiation prior to diagnosis as emerging risk factors for subgroups of patients with JDM. Air pollution may increase disease activity in pediatric SLE and other systemic autoimmune diseases, but such findings need to be confirmed.

Future investigations in this area will require adequately powered and controlled studies, examination of well-defined subgroups of patients whose risk factors may differ from the disease overall and confirmation of exposures through medical record review or validated biomarkers. Challenges include difficulties in assessing environmental exposures outside traditional medical system reporting and reporting biases in questionnaire studies. Also, the timing of exposures in relation to disease onset, the effects of intensity vs. duration of exposures, potential gender and age differences, interactions of multiple exposures and genetic factors and assessing mechanisms are all important areas for future investigations.

Many environmental exposures have not yet been investigated as possible risk factors for autoimmunity in children and should be prioritized based on animal model and in vitro data and identified risk factors in the adult-onset systemic autoimmune diseases. In addition, study designs that include populations with high levels of exposures in certain geographic regions or after accidental exposures may be productive.

Uncovering modifiable environmental factors for pediatric systemic autoimmune diseases will not only help with our understanding of disease mechanisms, but also help guide treatments and even potentially aide in the prevention of these diseases.

Lisa G. Rider, MD, is a pediatric rheumatologist and deputy chief of the Environmental Autoimmunity Group at the National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences, National Institutes of Health at the Clinical Research Center in Bethesda, Maryland. Her research has focused on juvenile myositis, including studies on environmental risk factors.

Lisa G. Rider, MD, is a pediatric rheumatologist and deputy chief of the Environmental Autoimmunity Group at the National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences, National Institutes of Health at the Clinical Research Center in Bethesda, Maryland. Her research has focused on juvenile myositis, including studies on environmental risk factors.

Frederick W. Miller, MD, PhD, is an adult rheumatologist and immunologist and is chief of the Environmental Autoimmunity Group at the National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences, National Institutes of Health at the Clinical Research Center in Bethesda, Maryland. He has focused on adult myositis and systemic rheumatic diseases, leading studies and working groups on environmental and genetic risk factors for these diseases in adults and children.

Frederick W. Miller, MD, PhD, is an adult rheumatologist and immunologist and is chief of the Environmental Autoimmunity Group at the National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences, National Institutes of Health at the Clinical Research Center in Bethesda, Maryland. He has focused on adult myositis and systemic rheumatic diseases, leading studies and working groups on environmental and genetic risk factors for these diseases in adults and children.

References

- Li YR, Zhao SD, Li J, et al. Genetic sharing and heritability of paediatric age of onset autoimmune diseases. Nat Commun. 2015 Oct 9;6:8442.

- Li YR, Li J, Zhao SD, et al. Meta-analysis of shared genetic architecture across ten pediatric autoimmune diseases. Nat Med. 2015 Sep;21(9):1018–1027.

- Feldman BM, Birdi N, Boone JE, et al. Seasonal onset of systemic-onset juvenile rheumatoid arthritis. J Pediatr. 1996 Oct;129(4):513–518.

- Berkun Y, Lewy H, Padeh S, Laron Z. Seasonality of birth of patients with juvenile idiopathic arthritis. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 2015 Jan–Feb;33(1):122–126.

- Nielsen HE, Dorup J, Herlin T, et al. Epidemiology of juvenile chronic arthritis: Risk dependent on sibship, parental income, and housing. J Rheumatol. 1999 Jul;26(7):1600–1605.

- Vegosen LJ, Weinberg CR, O’Hanlon TP, et al. Seasonal birth patterns in myositis subgroups suggest an etiologic role of early environmental exposures. Arthritis Rheum. 2007 Aug;56(8):2719–2728.

- Burns JC, Herzog L, Fabri O, et al. Seasonality of Kawasaki disease: A global perspective. PLoS One. 2013 Sep 18;8(9):e74529.

- Kao AS, Getis A, Brodine S, Burns JC. Spatial and temporal clustering of Kawasaki syndrome cases. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2008 Nov;27(11):981–985.

- Rodo X, Curcoll R, Robinson M, et al. Tropospheric winds from northeastern China carry the etiologic agent of Kawasaki disease from its source to Japan. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2014 Jun 3;111(22):7952–7957.

- Rodo X, Ballester J, Cayan D, et al. Association of Kawasaki disease with tropospheric wind patterns. Sci Rep. 2011;1:152.

- Rigante D, Bosco A, Esposito S. The etiology of juvenile idiopathic arthritis. Clin Rev Allergy Immunol. 2015 Oct;49(2):253–261.

- Berkun Y, Padeh S. Environmental factors and the geoepidemiology of juvenile idiopathic arthritis. Autoimmun Rev. 2010 Mar;9(5):A319–A324.

- Ellis JA, Munro JE, Ponsonby AL. Possible environmental determinants of juvenile idiopathic arthritis. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2010 Mar;49(3):411–425.

- Oen K, Fast M, Postl B. Epidemiology of juvenile rheumatoid arthritis in Manitoba, Canada, 1975–92: Cycles in incidence. J Rheumatol. 1995 Apr;22:745–750.

- Gonzalez B, Larranaga C, Leon O, et al. Parvovirus B19 may have a role in the pathogenesis of juvenile idiopathic arthritis. J Rheumatol. 2007 Jun;34(6):1336–1340.

- Lehmann HW, Knoll A, Kuster RM, Modrow S. Frequent infection with a viral pathogen, parvovirus B19, in rheumatic diseases of childhood. Arthritis Rheum. 2003 Jun;48(6):1631–1638.

- Horton DB, Scott FI, Haynes K, et al. Antibiotic exposure and juvenile idiopathic arthritis: A case-control study. Pediatrics. 2015 Aug;136(2):e333–e343.

- Arvonen M, Virta LJ, Pokka T, et al. Repeated exposure to antibiotics in infancy: A predisposing factor for juvenile idiopathic arthritis or a sign of this group’s greater susceptibility to infections? J Rheumatol. 2015 Mar;42(3):521–526.

- Tejesvi MV, Arvonen M, Kangas SM, et al. Faecal microbiome in new-onset juvenile idiopathic arthritis. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 2016 Mar;35(3):363–370.

- Lange L, Thiele GM, McCracken C, et al. Symptoms of periodontitis and antibody responses to Porphyromonas gingivalis in juvenile idiopathic arthritis. Pediatr Rheumatol Online J. 2016 Feb 9;14(1):8.

- Carlens C, Jacobsson L, Brandt L, et al. Perinatal characteristics, early life infections and later risk of rheumatoid arthritis and juvenile idiopathic arthritis. Ann Rheum Dis. 2009 Jul;68(7):1159–1164.

- Shenoi S, Shaffer ML, Wallace CA. Environmental risk factors and early-life exposures in juvenile idiopathic arthritis: A case-control study. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken). 2016 Aug;68(8):1186–1194.

- Miller J, Ponsonby AL, Pezic A, et al. Sibling exposure and risk of juvenile idiopathic arthritis. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2015 Jul;67(7):1951–1958.

- Shenoi S, Bell S, Wallace CA, Mueller BA. Juvenile idiopathic arthritis in relation to maternal prenatal smoking. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken). 2015 May;67(5):725–730.

- Radon K, Windstetter D, Poluda D, et al. Exposure to animals and risk of oligoarticular juvenile idiopathic arthritis: A multicenter case-control study. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2010 Apr 20;11:73.

- Principi N, Rigante D, Esposito S. The role of infection in Kawasaki syndrome. J Infect. 2013 Jul;67(1):1–10.

- Pachman LM, Hayford JR, Hochberg MC, et al. New-onset juvenile dermatomyositis: comparisons with a healthy cohort and children with juvenile rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 1997 Aug;40(8):1526–1533.

- Pachman LM, Lipton R, Ramsey-Goldman R, et al. History of infection before the onset of juvenile dermatomyositis: Results from the National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases Research Registry. Arthritis Rheum. 2005 Apr 15;53(2):166–172.

- Rider LG, Wu L, Mamyrova G, et al. Environmental factors preceding illness onset differ in phenotypes of the juvenile idiopathic inflammatory myopathies. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2010 Dec;49(12):2381–2390.

- Habers GE, Huber AM, Mamyrova G, et al. Brief report: Association of myositis autoantibodies, clinical features, and environmental exposures at illness onset with disease course in juvenile myositis. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2016 Mar;68(3):761–768.

- Mamyrova G, Rider LG, Haagenson L, et al. Parvovirus B19 and onset of juvenile dermatomyositis. JAMA. 2005 Nov 2;294(17):2170–2171.

- Pachman LM, Litt DL, Rowley AH, et al. Lack of detection of enteroviral RNA or bacterial DNA in magnetic resonance imaging-directed muscle biopsies from twenty children with active untreated juvenile dermatomyositis. Arthritis Rheum. 1995 Oct;38(10):1513–1518.

- McClain MT, Poole BD, Bruner BF, et al. An altered immune response to Epstein-Barr nuclear antigen 1 in pediatric systemic lupus erythematosus. Arthritis Rheum. 2006 Jan;54(1):360–368.

- Mason T, Rabinovich CE, Fredrickson DD, et al. Breast feeding and the development of juvenile rheumatoid arthritis. J Rheumatol. 1995 Jun;22(6):1166–1170.

- Rosenberg AM. Evaluation of associations between breast feeding and subsequent development of juvenile rheumatoid arthritis. J Rheumatol. 1996 Jun;23(6):1080–1082.

- Ellis JA, Ponsonby AL, Pezic A, et al. CLARITY-Childhood arthritis risk factor identification study. Pediatr Rheumatol Online J. 2012 Nov 15;10(1):37.

- Young KA, Parrish LA, Zerbe GO, et al. Perinatal and early childhood risk factors associated with rheumatoid factor positivity in a healthy paediatric population. Ann Rheum Dis. 2007 Feb;66(2):179–183.

- Hyrich KL, Baildam E, Pickford H, et al. Influence of past breast feeding on pattern and severity of presentation of juvenile idiopathic arthritis. Arch Dis Child. 2016 Apr;101(4):348–351.

- Orione MA, Silva CA, Sallum AM, et al. Risk factors for juvenile dermatomyositis: Exposure to tobacco and air pollutants during pregnancy. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken). 2014 Oct;66(10):1571–1575.

- Jaakkola JJ, Gissler M. Maternal smoking in pregnancy as a determinant of rheumatoid arthritis and other inflammatory polyarthropathies during the first 7 years of life. Int J Epidemiol. 2005 Jun;34(3):664–671.

- Butz AM, Rosenstein BJ. Passive smoking among children with chronic respiratory disease. J Asthma. 1992;29(4):265–272.

- Zeft AS, Prahalad S, Lefevre S, et al. Juvenile idiopathic arthritis and exposure to fine particulate air pollution. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 2009 Sep–Oct;27(5):877–884.

- Zeft AS, Prahalad S, Schneider R, et al. Systemic onset juvenile idiopathic arthritis and exposure to fine particulate air pollution. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 2016 Sep–Oct;34(5):946–952.

- Zeft AS, Burns JC, Yeung RS, et al. Kawasaki disease and exposure to fine particulate air pollution. J Pediatr. 2016 Oct;177:179–183.

- Vidotto JP, Pereira LA, Braga AL, et al. Atmospheric pollution: Influence on hospital admissions in paediatric rheumatic diseases. Lupus. 2012 Apr;21(5):526–533.

- Fernandes EC, Silva CA, Braga AL, et al. Exposure to air pollutants and disease activity in juvenile-onset systemic lupus erythematosus patients. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken). 2015 Nov;67(11):1609–1614.

- Neufeld KM, Karunanayake CP, Maenz LY, Rosenberg AM. Stressful life events antedating chronic childhood arthritis. J Rheumatol. 2013 Oct;40(10):1756–1765.

- Shah M, Targoff IN, Rice MM, et al. Brief report: Ultraviolet radiation exposure is associated with clinical and autoantibody phenotypes in juvenile myositis. Arthritis Rheum. 2013 Jul;65(7):1934–1941.

- Miller FW, Alfredsson L, Costenbader KH, et al. Epidemiology of environmental exposures and human autoimmune diseases: Findings from a National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences Expert Panel Workshop. J Autoimmun. 2012 Dec;39(4):259–271.

- Sparks JA, Costenbader KH. Genetics, environment, and gene-environment interactions in the development of systemic rheumatic diseases. Rheum Dis Clin North Am. 2014 Nov;40(4):637–657.

- Karlson EW, Deane K. Environmental and gene-environment interactions and risk of rheumatoid arthritis. Rheum Dis Clin North Am. 2012 May;38(2):405–426.

Disclosures

This research was supported by the Intramural Research Program of the NIH, National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences.

Key Points

- A role for environmental factors in juvenile idiopathic arthritis (JIA) and other pediatric systemic autoimmune diseases is emerging.

- Early life infections and antimicrobial use are risk factors for JIA.

- Premature or post-term birth, fewer siblings in the family, air pollution, infection and ultraviolet light may be risk factors for JIA and other pediatric systemic autoimmune diseases, but further studies are needed.