Clinical Vignette

A 45-year-old woman with long-standing asthma and chronic sinusitis has new-onset peripheral neuropathy, arthralgias, fatigue, progressive dyspnea and a nonproductive cough. She has never smoked and has no environmental exposures. Her medications include an albuterol metered-dose inhaler (which she uses daily); an inhaled corticosteroid, montelukast; and ibuprofen (which she takes occasionally). She is afebrile and normotensive. Her resting oxygen saturation on room air, measured by pulse oximetry, is 98%. She has an occasional audible wheeze on respiratory examination. Her musculoskeletal exam is unremarkable. There is no synovitis. There is no rash. Her neurologic exam reveals a mild sensory neuropathy affecting most of her right foot.

Laboratory studies reveal a white blood cell count of 11.5 K/uL with 28% eosinophils. Her hemoglobin and platelet counts are normal. Serum creatinine is 0.8 mg/dL with a normal urinalysis. Her hepatic function panel is normal. Serum immunoglobulins are notable for a mildly elevated serum IgE. Erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) is mildly elevated at 30 mm/hr, and the creatine phosphokinase is normal. ANA is borderline at 1:160 titer with a homogeneous pattern, and the extractable nuclear antigen profile is negative. The rheumatoid factor is borderline elevated at 18 IU/mL. The anti-CCP is negative, and C-ANCA, P-ANCA, MPO and PR-3 are also negative.

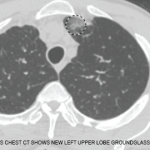

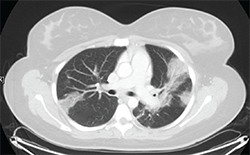

Figure 1: Thoracic high-resolution computed tomography (HRCT) scan with moderate diffuse bilateral infiltrates.

Pulmonary function testing reveals a moderate obstructive defect (FEV-1/FVC = 62%) with a 15% improvement following administration of an inhaled bronchodilator. A thoracic high-resolution computed tomography (HRCT) scan demonstrates patchy bilateral infiltrates (see Figure 1). Bronchoalveolar lavage reveals eosinophilia (10%), with negative cytology and microbiology studies. Electromyography of the upper and lower extremities demonstrates a symmetric sensory polyneuropathy, greatest in the right leg.

Discussion

The patient described in this vignette has a condition most consistent with eosinophilic granulomatosis with polyangiitis (EGPA, known as Churg-Strauss syndrome prior to the 2012 Chapel Hill Consensus Conference). An important clue to this patient’s diagnosis is the presence of peripheral blood eosinophilia. An increase in the eosinophil count is observed frequently, and rheumatologists are often asked to opine regarding the diagnosis and management of systemic eosinophilia.

In addition to EGPA, many other entities should be considered, and establishing an accurate diagnosis is critical to ensure appropriate management.

In this review, we discuss several eosinophilic disorders that rheumatologists may encounter, with the goal of providing a practical guide to the evaluation of eosinophilia.

Differential Diagnosis

When evaluating a patient with eosinophilia, it’s important to review the patient’s history and exclude the most common causes of eosinophilia—medications and infectious causes (see Table 1). A history of novel medication use in association with eosinophilia likely suggests that allergic eosinophilic inflammation is occurring; this can manifest with rash, pulmonary infiltrates and systemic features, such as fever. Although virtually any medication may be implicated, antibiotics and nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) are particularly associated with a peripheral eosinophilia.