(Click for larger image)

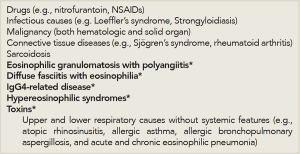

Table 1: Differential Diagnosis of Systemic Eosinophilia for the Rheumatologist.

*Etiologies specifically discussed in this review

A history of travel abroad should raise suspicions for an infectious etiology, because many infections associated with significant eosinophilia are due to helminths.

Loeffler’s syndrome refers to transient pulmonary infiltrates with eosinophilia that occurs in response to passage of helminthic larvae through the lungs.

Other potential infectious causes of eosinophilia include fungal infections and tuberculosis (TB).

Malignancy must also be considered in the general workup of eosinophilia. Hematologic malignancies may be primarily eosinophilic in nature or have associated reactive eosinophilia, in the case of some lymphoid neoplasms. Solid-organ malignancies may also present with associated peripheral eosinophilia.

While these common causes are considered, one should also proceed with the workup for less common causes of eosinophilia, including autoimmune, idiopathic inflammatory and idiopathic systemic etiologies. Although eosinophilia is occasionally associated with the connective tissue diseases commonly encountered by the rheumatologist, including rheumatoid arthritis and Sjögren’s syndrome, a thorough approach to exclude other potential causes is necessary.

Below, we focus on the approach to eosinophilia and several idiopathic entities (e.g., EGPA, diffuse fasciitis with eosinophilia, IgG4-related disease and hypereosinophilic syndromes) that represent part of a rheumatologist’s differential diagnosis for eosinophilia (see Table 1)—after medication effects, infection, malignancy and connective tissue diseases are considered.

Evaluation

As part of the history, the rheumatologist should ask about constitutional symptoms, such as fever and weight loss, and assess for physical findings of cardiac, gastrointestinal, neurologic, dermatologic and genitourinary involvement, all of which may provide clues to a specific etiology. Laboratory testing (including measurements of blood eosinophils, cultures and serologic markers of inflammation), spirometry and thoracic radiographic imaging may help distinguish between different diseases.

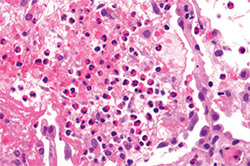

When pulmonary infiltrates are identified, bronchoalveolar lavage, transbronchial or even surgical lung biopsy may aid in the diagnostic evaluation, and a variety of etiologies should be considered. Pulmonary eosinophilia in the context of peripheral eosinophilia may be a prominent feature of a multi-organ process, as in EGPA or the hypereosinophilic syndromes, or may be single-organ in nature, as in the eosinophilic pneumonias (see Figure 2).1 Further, noninvasive diagnostic studies or even biopsy of other affected organs (e.g., echocardiogram, electromyogram or bone marrow biopsy) can be useful in the workup of systemic eosinophilia as clinically indicated.

Eosinophilic Granulomatosis with Polyangiitis

EGPA is now defined exclusively as a vasculitis.2 However, EGPA may be more practically viewed as a systemic eosinophilic disease that may or may not have prominent vasculitic features. It may be useful to view the syndrome of EGPA through the lens of pulmonary eosinophilia rather than strictly within the prism of vasculitis. With such a perspective, EGPA may be considered as being on a continuum with eosinophilic asthma, as well as chronic eosinophilic pneumonia—an entity characterized by respiratory symptoms, hypoxemia, pulmonary infiltrates, sinusitis and a similar degree of peripheral eosinophilia as EGPA.