Clinical Vignette

A 45-year-old woman with long-standing asthma and chronic sinusitis has new-onset peripheral neuropathy, arthralgias, fatigue, progressive dyspnea and a nonproductive cough. She has never smoked and has no environmental exposures. Her medications include an albuterol metered-dose inhaler (which she uses daily); an inhaled corticosteroid, montelukast; and ibuprofen (which she takes occasionally). She is afebrile and normotensive. Her resting oxygen saturation on room air, measured by pulse oximetry, is 98%. She has an occasional audible wheeze on respiratory examination. Her musculoskeletal exam is unremarkable. There is no synovitis. There is no rash. Her neurologic exam reveals a mild sensory neuropathy affecting most of her right foot.

Laboratory studies reveal a white blood cell count of 11.5 K/uL with 28% eosinophils. Her hemoglobin and platelet counts are normal. Serum creatinine is 0.8 mg/dL with a normal urinalysis. Her hepatic function panel is normal. Serum immunoglobulins are notable for a mildly elevated serum IgE. Erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) is mildly elevated at 30 mm/hr, and the creatine phosphokinase is normal. ANA is borderline at 1:160 titer with a homogeneous pattern, and the extractable nuclear antigen profile is negative. The rheumatoid factor is borderline elevated at 18 IU/mL. The anti-CCP is negative, and C-ANCA, P-ANCA, MPO and PR-3 are also negative.

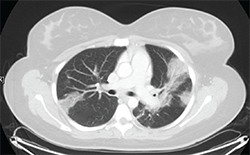

Figure 1: Thoracic high-resolution computed tomography (HRCT) scan with moderate diffuse bilateral infiltrates.

Pulmonary function testing reveals a moderate obstructive defect (FEV-1/FVC = 62%) with a 15% improvement following administration of an inhaled bronchodilator. A thoracic high-resolution computed tomography (HRCT) scan demonstrates patchy bilateral infiltrates (see Figure 1). Bronchoalveolar lavage reveals eosinophilia (10%), with negative cytology and microbiology studies. Electromyography of the upper and lower extremities demonstrates a symmetric sensory polyneuropathy, greatest in the right leg.

Discussion

The patient described in this vignette has a condition most consistent with eosinophilic granulomatosis with polyangiitis (EGPA, known as Churg-Strauss syndrome prior to the 2012 Chapel Hill Consensus Conference). An important clue to this patient’s diagnosis is the presence of peripheral blood eosinophilia. An increase in the eosinophil count is observed frequently, and rheumatologists are often asked to opine regarding the diagnosis and management of systemic eosinophilia.

In addition to EGPA, many other entities should be considered, and establishing an accurate diagnosis is critical to ensure appropriate management.

In this review, we discuss several eosinophilic disorders that rheumatologists may encounter, with the goal of providing a practical guide to the evaluation of eosinophilia.

Differential Diagnosis

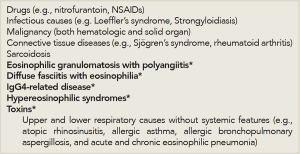

When evaluating a patient with eosinophilia, it’s important to review the patient’s history and exclude the most common causes of eosinophilia—medications and infectious causes (see Table 1). A history of novel medication use in association with eosinophilia likely suggests that allergic eosinophilic inflammation is occurring; this can manifest with rash, pulmonary infiltrates and systemic features, such as fever. Although virtually any medication may be implicated, antibiotics and nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) are particularly associated with a peripheral eosinophilia.

(Click for larger image)

Table 1: Differential Diagnosis of Systemic Eosinophilia for the Rheumatologist.

*Etiologies specifically discussed in this review

A history of travel abroad should raise suspicions for an infectious etiology, because many infections associated with significant eosinophilia are due to helminths.

Loeffler’s syndrome refers to transient pulmonary infiltrates with eosinophilia that occurs in response to passage of helminthic larvae through the lungs.

Other potential infectious causes of eosinophilia include fungal infections and tuberculosis (TB).

Malignancy must also be considered in the general workup of eosinophilia. Hematologic malignancies may be primarily eosinophilic in nature or have associated reactive eosinophilia, in the case of some lymphoid neoplasms. Solid-organ malignancies may also present with associated peripheral eosinophilia.

While these common causes are considered, one should also proceed with the workup for less common causes of eosinophilia, including autoimmune, idiopathic inflammatory and idiopathic systemic etiologies. Although eosinophilia is occasionally associated with the connective tissue diseases commonly encountered by the rheumatologist, including rheumatoid arthritis and Sjögren’s syndrome, a thorough approach to exclude other potential causes is necessary.

Below, we focus on the approach to eosinophilia and several idiopathic entities (e.g., EGPA, diffuse fasciitis with eosinophilia, IgG4-related disease and hypereosinophilic syndromes) that represent part of a rheumatologist’s differential diagnosis for eosinophilia (see Table 1)—after medication effects, infection, malignancy and connective tissue diseases are considered.

Evaluation

As part of the history, the rheumatologist should ask about constitutional symptoms, such as fever and weight loss, and assess for physical findings of cardiac, gastrointestinal, neurologic, dermatologic and genitourinary involvement, all of which may provide clues to a specific etiology. Laboratory testing (including measurements of blood eosinophils, cultures and serologic markers of inflammation), spirometry and thoracic radiographic imaging may help distinguish between different diseases.

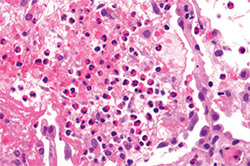

When pulmonary infiltrates are identified, bronchoalveolar lavage, transbronchial or even surgical lung biopsy may aid in the diagnostic evaluation, and a variety of etiologies should be considered. Pulmonary eosinophilia in the context of peripheral eosinophilia may be a prominent feature of a multi-organ process, as in EGPA or the hypereosinophilic syndromes, or may be single-organ in nature, as in the eosinophilic pneumonias (see Figure 2).1 Further, noninvasive diagnostic studies or even biopsy of other affected organs (e.g., echocardiogram, electromyogram or bone marrow biopsy) can be useful in the workup of systemic eosinophilia as clinically indicated.

Eosinophilic Granulomatosis with Polyangiitis

EGPA is now defined exclusively as a vasculitis.2 However, EGPA may be more practically viewed as a systemic eosinophilic disease that may or may not have prominent vasculitic features. It may be useful to view the syndrome of EGPA through the lens of pulmonary eosinophilia rather than strictly within the prism of vasculitis. With such a perspective, EGPA may be considered as being on a continuum with eosinophilic asthma, as well as chronic eosinophilic pneumonia—an entity characterized by respiratory symptoms, hypoxemia, pulmonary infiltrates, sinusitis and a similar degree of peripheral eosinophilia as EGPA.

In a large retrospective study recently published by the French Vasculitis Study Group to better define the real-world EGPA experience, the clinical characteristics of 383 patients with EGPA were described.3 Interestingly, only 31% were ANCA positive, and those that were ANCA negative had lower BVAS scores than those who were ANCA positive (18.4 vs. 20.7), with less frequent renal disease, peripheral neuropathy and otolaryngeal disease. Anecdotally, pulmonologists frequently encounter a population of patients with features strongly suggestive of EGPA that is characterized by ANCA negativity, prominent sinus and lower respiratory features, including severe asthma symptoms, and pulmonary infiltrates, in the setting of high-grade peripheral eosinophilia—and importantly, no evidence of vasculitis.

The dichotomies that exist under the umbrella of EGPA—ANCA positive vs. ANCA negative, respiratory predominant symptoms vs. systemic symptoms, vasculitic vs. nonvasculitic—may ultimately prove to have implications for treatment. However, corticosteroids remain the mainstay of therapy, and chronic low-dose steroids can often control disease activity in ANCA-negative patients with predominant respiratory manifestations. In patients with greater systemic manifestations and suspected active vasculitis that may be more commonly seen in rheumatology practices, a greater degree of immunosuppression (e.g., cyclophosphamide, azathioprine, mycophenolate mofetil) is often required for both induction and maintenance therapy—similar to approaches for other forms of systemic vasculitis. Mepolizumab (GlaxoSmithKline) and Reslizumab (Teva), monoclonal antibodies directed against interleukin 5 (IL-5, i.e., a cytokine that has a key central role in the differentiation, survival and migration of eosinophils), are investigational agents that specifically target eosinophils and represent promising novel therapeutic options for EGPA of all phenotypes.

In open-label pilot studies, blocking IL-5 with mepolizumab has been observed to allow for reduction in corticosteroid dosage with EGPA.4 Mepolizumab is currently being studied in a placebo-controlled, double-blind trial in patients with refractory or relapsing EGPA (clinicaltrials.gov identifier: NCT02020889).

Diffuse Fasciitis with Eosinophilia

Another eosinophilic disorder that may present to the rheumatologist is diffuse fasciitis with eosinophilia (DFE), also called eosinophilic fasciitis or Shulman’s syndrome, an idiopathic disease classically characterized by woody induration of the skin and peripheral and tissue eosinophilia.5,6 Although the etiology of this disease is not known, in some cases, a history of recent, severe exertion has been associated with its development. A hallmark of DFE is extensive skin thickening, and it is important to distinguish this condition from that of systemic scleroderma (SSc).5,7

The clinical features of DFE include severely indurated and thickened skin, typically symmetric in nature and involving the proximal extremities. Truncal involvement is common. Autoantibody negativity and the presence of peripheral eosinophilia distinguish DFE from SSc. Similarly, the distal extremities and face are typically spared, and importantly, there is an absence of Raynaud’s phenomenon or other internal organ manifestations characteristic of SSc.5,7 This proximal skin involvement—with sparing of distal extremities—is one of the critical clues to differentiating DFE from SSc.5,7 The woody induration may give a characteristic peau d’orange appearance. The severe fibrosis of the fascia can result in limitations in range of motion and permanent flexion contractures of the involved extremities.

Laboratory abnormalities are often limited to the finding of peripheral eosinophilia. The eosinophilia is typically present early in the disease course, but may not be persistent and often the presence or degree of peripheral eosinophilia does not correlate with the severity of the fasciitis. Elevated serologic inflammatory markers (e.g., ESR and CRP) and polyclonal hypergammaglobulinemia can be seen, and—in contrast to SSc patients—these patients typically are autoantibody negative.

The diagnosis of DFE usually requires a full-thickness en bloc biopsy of the affected area—deep enough to include skin, fascia and muscle. The fascia will characteristically show features of both fibrosis and inflammation; with a plasmalymphocytic and prominent eosinophilic cellular infiltration.

The clinical course of DFE varies from a self-limited process that improves within a few years to one of chronic-active or recurrent fasciitis. DFE is typically treated with immunosuppressive medications that include corticosteroids followed by maintenance therapy, with corticosteroid-sparing agents, such as methotrexate.5,7,8

Eosinophilia Myalgia Syndrome & Toxic Oil Syndrome

Two historic entities, eosinophilia myalgia syndrome (EMS) and toxic oil syndrome (TOS), presented with similar clinical and histopathologic findings as DFE. Each occurred in epidemic form after specific environmental exposures. TOS occurred in Spain in 1981 and affected ~20,000 people. It was related to the ingestion of rapeseed oil denatured with the chemical, aniline, which was present in a specific cooking oil.5

When evaluating a patient with eosinophilia, it’s important to review the patient’s history & exclude the most common causes of eosinophilia—medications & infectious causes.

EMS occurred in epidemic form in 1989 in the U.S., affected ~1,500 people and was associated with ingestion of contaminated forms of L-tryptophan.5

These eosinophilic disorders are exceedingly rare, but highlight the potential for novel causes of eosinophilia to emerge.

Hypereosinophilic Syndromes

The hypereosinophilic syndromes are a heterogeneous group of diseases characterized by persistent eosinophilia of >1,500 eosinophils/mm3 in association with end-organ damage or dysfunction in the absence of secondary causes of eosinophilia.9

The predominant hypereosinophilic syndrome subtypes are the myeloproliferative and lymphocytic variants. Familial, undefined and overlap syndromes with incomplete criteria are less common subtypes. The myeloproliferative variant may be divided into three subgroups: 1) chronic eosinophilic leukemia with demonstrable cytogenetic abnormalities and/or blasts on peripheral smear; 2) the PDGFRA-associated hypereosinophilic syndrome, attributed to a constitutively activated tyrosine kinase fusion protein (Fip1L1-PDGFRα) due to a chromosomal deletion on 4q12; this variant is often responsive to imatinib; and 3) the FIP1-negative variant associated with clonal eosinophilia and associated with dysplastic peripheral eosinophils, increased serum vitamin-B12, increased tryptase, anemia, thrombocytopenia, splenomegaly, bone marrow cellularity >80%, spindle-shaped mast cells and myelofibrosis.10

If hypereosinophilic syndromes are being strongly considered in the evaluation of a patient with eosinophilia, bone marrow biopsy can be a valuable addition to the diagnostic workup. Corticosteroids and other immunosuppressive agents are the mainstay of treatment.

IgG4-Related Disease

IgG4-related disease (IgG4-RD) is a disorder associated with peripheral eosinophilia. IgG4-RD is a fibro-inflammatory condition characterized by dense lymphoplasmacytic infiltrative lesions composed largely of IgG4-positive plasma cells, and areas of fibrosis, and is frequently associated with elevated serum IgG4 levels.11,12 IgG4-RD can affect nearly every organ system, and patients with this disease have a predilection for forming fibro-inflammatory mass lesions within affected organs.11,12 IgG4-RD can be associated with allergic or atopic diseases. Thus, patients with IgG4-RD often have longstanding histories of allergic rhinitis or asthma, and many have elevated serum levels of IgE. Peripheral eosinophilia may be seen with IgG4-RD and moderate eosinophilic infiltration is commonly identified on histopathologic samples of the fibro-inflammatory lesions.11,12

Summary, Conclusion & Future Directions

The presence of elevated levels of blood and/or tissue eosinophils is common to all of the conditions discussed in this focused review. Although the eosinophil plays an important role in each of these syndromes, there are important clinical and pathologic differences, as well as differences in prognosis and treatment paradigms. Recognition of these entities by the treating rheumatologist and early intervention with appropriate treatment can prevent significant morbidity and prevent eosinophilic organ damage. Although the cornerstone of treatment for each of these therapies generally involves systemic corticosteroids or the addition of traditional corticosteroid-sparing agents, novel therapies are emerging that target cytokines, such as IL-4 or IL-5, and provide hope to the many patients affected by eosinophilia.

Praveen Akuthota, MD, works in the Division of Pulmonary, Critical Care, & Sleep Medicine at Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center in Boston and is an assistant professor of medicine at Harvard Medical School.

Praveen Akuthota, MD, works in the Division of Pulmonary, Critical Care, & Sleep Medicine at Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center in Boston and is an assistant professor of medicine at Harvard Medical School.

Aryeh Fischer, MD, is associate professor of medicine in the Department of Medicine at the University of Colorado School of Medicine in Denver.

Aryeh Fischer, MD, is associate professor of medicine in the Department of Medicine at the University of Colorado School of Medicine in Denver.

Michael E. Wechsler, MD, is a professor of medicine and director of the Asthma Program in the Department of Medicine at National Jewish Health in Denver.

Michael E. Wechsler, MD, is a professor of medicine and director of the Asthma Program in the Department of Medicine at National Jewish Health in Denver.

Disclosure Statement

The corresponding author, Dr. Wechsler, has received research support from a joint-sponsored NIH and GlaxoSmithKline study of mepolizumab for EGPA. He has also received honoraria for consulting, advisory boards and lectures from Teva, AstraZeneca, Boston Scientific, Novartis, Sanofi, Vectura, Sunovion, Regeneron and Ambit Bioscience.

References

- Akuthota P, Weller PF. Eosinophilic pneumonias. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2012 Oct;25(4):649–660.

- Jennette JC, Falk RJ, Bacon PA, et al. 2012 revised International Chapel Hill Consensus Conference Nomenclature of Vasculitides. Arthritis Rheum. 2013 Jan;65(1):1–11.

- Comarmond C, Pagnoux C, Khellaf M, et al. Eosinophilic granulomatosis with polyangiitis (Churg-Strauss): Clinical characteristics and long-term followup of the 383 patients enrolled in the French Vasculitis Study Group cohort. Arthritis Rheum. Jan;65(1):270–281.

- Kim S, Marigowda G, Oren E, et al. Mepolizumab as a steroid-sparing treatment option in patients with Churg-Strauss syndrome. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2010 Jun;125(6):1336–1343.

- Bolster MB, Silver RM. Eosinophilia-myalgia syndrome, toxic-oil syndrome, and diffuse fasciitis with eosinophilia. Curr Opin Rheumatol. 1994 Nov;6(6):642–649.

- Shulman LE. Diffuse fasciitis with eosinophilia: A new syndrome? Trans Assoc Am Physicians. 1975;88:70–86.

- Silver RM. Eosinophilia-myalgia syndrome, toxic-oil syndrome, and diffuse fasciitis with eosinophilia. Curr Opin Rheumatol. 1993 Nov;5(6):802–808. Review.

- Lakhanpal S, Ginsburg WW, Michet CJ, et al. Eosinophilic fasciitis: Clinical spectrum and therapeutic response in 52 cases. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 1988 May;17(4):221–231.

- Valent P, Klion AD, Horny HP, et al. Contemporary consensus proposal on criteria and classification of eosinophilic disorders and related syndromes. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2012 Sep;130(3):607–612.e9.

- Simon HU, Rothenberg ME, Bochner BS, et al. Refining the definition of hypereosinophilic syndrome. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2010 Jul;126(1):45–49.

- Stone JH. IgG4-related disease: Nomenclature, clinical features, and treatment. Semin Diagn Pathol. 2012 Nov;29(4):177–190.

- Stone JH, Zen Y, Deshpande V. IgG4-related disease. N Engl J Med. 2012 Feb 9;366(6):539–551.