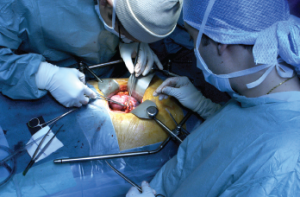

Surgeons performing a kidney transplant

AJPhoto / Science Source

Despite our best efforts and modern interventions, we still have patients in the intensive care unit with organ failure. Although renal failure can be mitigated by dialysis, patients with cardiac or respiratory failure secondary to active autoimmune disease raise difficult clinical and ethical issues. Two recent cases, both with organ failure, led us to examine the practice of organ transplant in active autoimmune disease. Can patients with active autoimmune disease be transplanted? How long do they need to be in remission prior to being considered a transplant candidate? How is disease control defined and by whom?

Case 1

An adolescent female with systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) and end-stage renal disease (ESRD) on dialysis secondary to uncontrolled lupus nephritis presented with fever and bacteremia. Her evaluation revealed Libman-Sacks endocarditis with secondary bacterial endocarditis requiring mitral valve replacement. Following surgery, she had cardiac arrest and required emergent cannulation for extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO). She was intolerant to ECMO weaning, and the only hope for survival was a heart transplant.

Case 2

A toddler-aged female presented with fever, hypoxia and respiratory distress. Additional history revealed musculoskeletal involvement, fatigue, fever and weight loss over the past year. She had nailfold capillary changes and old Gottron’s papules. Her workup revealed a pneumothorax and diffuse ground glass opacities without focal consolidations. An open lung biopsy showed subacute diffuse alveolar damage. She was subsequently diagnosed with anti-MDA5-associated amyopathic juvenile dermatomyositis with rapidly progressive interstitial lung disease. She exceeded the limits of mechanical ventilation and was placed on ECMO. While on ECMO, she received aggressive therapy, but was eventually determined to need a lung transplant.

Discussion

ECMO is indicated for patients with potentially reversible cardiopulmonary failure to permit time for various therapies to become effective and to allow for any potential organ recovery.1 The ethical principle of beneficence is often a prime consideration with initiation of ECMO, because it is a potentially life-saving therapy. However, we must weigh this option with the principle of nonmaleficence when we consider patients who may end up with a bridge to nowhere, when they are later denied an organ transplant secondary to active autoimmune disease. For these patients, it becomes a heartbreaking choice for all involved parties who are forced to make the decision to withdraw support.

Organ transplantation itself is fraught with ethical dilemmas due to the scarcity of available organs, potential uncertainty of transplant outcomes (even for ideal candidates), financial barriers and the need for intensive long-term follow-up.2