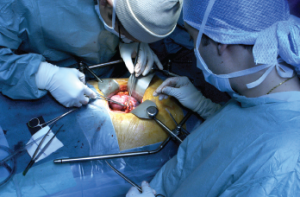

Surgeons performing a kidney transplant

AJPhoto / Science Source

Despite our best efforts and modern interventions, we still have patients in the intensive care unit with organ failure. Although renal failure can be mitigated by dialysis, patients with cardiac or respiratory failure secondary to active autoimmune disease raise difficult clinical and ethical issues. Two recent cases, both with organ failure, led us to examine the practice of organ transplant in active autoimmune disease. Can patients with active autoimmune disease be transplanted? How long do they need to be in remission prior to being considered a transplant candidate? How is disease control defined and by whom?

Case 1

An adolescent female with systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) and end-stage renal disease (ESRD) on dialysis secondary to uncontrolled lupus nephritis presented with fever and bacteremia. Her evaluation revealed Libman-Sacks endocarditis with secondary bacterial endocarditis requiring mitral valve replacement. Following surgery, she had cardiac arrest and required emergent cannulation for extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO). She was intolerant to ECMO weaning, and the only hope for survival was a heart transplant.

Case 2

A toddler-aged female presented with fever, hypoxia and respiratory distress. Additional history revealed musculoskeletal involvement, fatigue, fever and weight loss over the past year. She had nailfold capillary changes and old Gottron’s papules. Her workup revealed a pneumothorax and diffuse ground glass opacities without focal consolidations. An open lung biopsy showed subacute diffuse alveolar damage. She was subsequently diagnosed with anti-MDA5-associated amyopathic juvenile dermatomyositis with rapidly progressive interstitial lung disease. She exceeded the limits of mechanical ventilation and was placed on ECMO. While on ECMO, she received aggressive therapy, but was eventually determined to need a lung transplant.

Discussion

ECMO is indicated for patients with potentially reversible cardiopulmonary failure to permit time for various therapies to become effective and to allow for any potential organ recovery.1 The ethical principle of beneficence is often a prime consideration with initiation of ECMO, because it is a potentially life-saving therapy. However, we must weigh this option with the principle of nonmaleficence when we consider patients who may end up with a bridge to nowhere, when they are later denied an organ transplant secondary to active autoimmune disease. For these patients, it becomes a heartbreaking choice for all involved parties who are forced to make the decision to withdraw support.

Organ transplantation itself is fraught with ethical dilemmas due to the scarcity of available organs, potential uncertainty of transplant outcomes (even for ideal candidates), financial barriers and the need for intensive long-term follow-up.2

Currently, there are no standard guidelines for organ transplantation with active autoimmune disease. The government organization, Organ Procurement and Transplantation Network (OPTN), and organ procurement organizations (OPOs), such as United Network for Organ Sharing (UNOS), do not have uniform guidelines for transplantation with rheumatic disease and defer to the local transplant team to make its own decisions.3

Centers vary in their definition of disease inactivity and requirements for how long disease must be inactive. At our institution, it is recommended that patients with ESRD on dialysis achieve disease quiescence for one year prior to transplant. Renal transplant literature suggests that patients may be maintained on dialysis for as little as three months before transplantation because end-stage renal disease often leads to a burnout effect of active SLE disease.4 Our diseases are rare, and data on organ transplant besides kidneys are limited.

Among adult lung transplants performed between 1995 and 2015, only 0.7% of all transplants were for connective tissue disease, 2.5% were for sarcoidosis, and 1.6% were for non-idiopathic pulmonary artery hypertension.5 The selection process may vary by center, there are no absolute guidelines, and the decision to transplant depends upon the center’s practices, waiting list and other factors.6

International consensus guidelines on lung transplantation state that systemic disease quiescence should be achieved, including any evidence of active vasculitis, before transplant, but provides no further guidance on timeline or definition of quiescence.7

Prognosis estimates of CVD with pulmonary involvement is largely from the scleroderma population. Poor prognostic indicators include old age and reduced lung capacity.8 Many patients with scleroderma have had successful lung transplantations, but at this time, data are insufficient to inform specific guidelines for patients with other rheumatic diseases.

Outcome data on heart transplant in systemic lupus erythematosus are limited to case reports.9-14

Back to Our Cases

Our adolescent patient with SLE was not deemed a transplant candidate due to concern for ongoing disease activity, a history of noncompliance and the need for cardiac and, eventual, kidney transplant. Cardiac biopsies did not reveal myocarditis and/or vasculitis, and an attempt to control the patient’s disease with cyclophosphamide, rituximab, intravenous immunoglobulin, plasma exchange and corticosteroids was not successful. With her severe right ventricular dysfunction, she was unable to tolerate attempts at weaning ECMO. Without a possibility for transplant and due to the risk of infection with ongoing immunosuppression, a left-ventricular assist device was not an option. The medical team and the parents made the decision to withdraw support. After 19 days on ECMO, she died upon disconnection of the circuit.

Our second case received multiple therapies including corticosteroids, intravenous immunoglobulin, cyclophosphamide, rituximab, azathioprine, hydroxychloroquine, and plasma exchange; however, she was unable to come off of ECMO. She was evaluated by the lung transplant team, but was not felt to be an appropriate lung transplant candidate due to prolonged ECMO course (39 days), deconditioned state and concern for persistent active disease. The care team and the family made the decision to discontinue ECMO contingent upon the arrival of distant family members, but prior to this, she died suddenly of cardiac arrest after 71 days on ECMO.

Lessons Learned

These experiences highlight a critical need for further development of guidelines and research in this area, particularly because the prevalence of autoimmune disease continues to rise. There is a need for transparent discussion among transplant teams, physicians and families regarding whether a patient is an organ transplant candidate as early in the course as possible.

We learned from these two cases; however, more uncertainties than answers remain when rheumatology patients with active disease are in need of organ transplant.

W. Blaine Lapin, MD, and Jennifer L. Rammel, MD, MPH, are second-year pediatric rheumatology fellows at Baylor College of Medicine, Texas Children’s Hospital, Houston.

Andrea A. Ramirez, MD, MEd, is an assistant professor of pediatrics and associate program director of the pediatric rheumatology fellowship at Baylor College of Medicine, Texas Children’s Hospital, Houston.

References

- MacLaren G, Conrad S, Peek G. Extracorporeal life support organization (ELSO): Indications for pediatric respiratory extracorporeal life support [expires March 2018]. 2015 Mar.

- Committee on Hospital Care, Section on Surgery, and Section on Critical Care. Policy statement—pediatric organ donation and transplantation. Pediatrics. 2010 Apr;125(4):822–828.

- Organ Procurement and Transplantation Network (OPTN) Policies Manual.

- Lionaki S, Skalioti C, Boletis JN. Kidney transplantation in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus. World J Transplant. 2014 Sep 24;4(3):176–182.

- Yusen RD, Edwards LB, Dipchand AI, et al. The registry of the International Society for Heart and Lung Transplantation: Thirty-third adult lung and heart–lung transplant report—2016; Focus theme: Primary diagnostic indications for transplant. J Heart Lung Transplant. 2016 Oct;35(10):1170–1184.

- Verleden GM, Dupont L, Yserbyt J, et al. Recipient selection process and listing for lung transplantation. J Thorac Dis. 2017 Sep;9(9):3372–3384.

- Weill D, Benden C, Corris PA, et al. A consensus document for the selection of lung transplant candidates: 2014—an update from the Pulmonary Transplantation Council of the International Society for Heart and Lung Transplantation. J Heart Lung Transplant. 2015 Jan;34(1):1–15.

- Orens JB, Estenne M, Arcasoy S, et al. International guidelines for the selection of lung transplant candidates: 2006 Update—A consensus report from the Pulmonary Scientific Council of the International Society for Heart and Lung Transplantation. J Heart Lung Transplant. 2006 Jul;25(7):745–755.

- VanderPluym CJ, Rebeyka I, Buchholz H. Successful bridge to transplantation for pediatric lupus cardiomyopathy. J Heart Lung Transplant. 2012 Jan;31(1):110–111.

- Hsu RB, Tsai MK, Lee PH, et al. Simultaneous heart and kidney transplantation from a single donor. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2008 Dec 1;34(6):1179–1184.

- Tweezer-Zaks N, Zandman-Goddard G, Lidar M, et al. A long-term follow-up after cardiac transplantation in a lupus patient: Case report and review of the literature. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2007 Sep;1110:539–543.

- Wang SS, Chou NK, Chi NH, et al. Simultaneous heart and kidney transplantation for combined cardiac and renal failure. Transplant Proc. 2006 Sep;38(7):2135–2137.

- Levy RD, Guerraty AJ, Yacoub MH, Loertscher R. Prolonged survival after heart-lung transplantation in systemic lupus erythematosus. Chest. 1993 Dec;104(6):1903–1905.

- DiSesa VJ, Sloss LJ, Cohn LH. Heart transplantation for intractable prosthetic valve endocarditis. J Heart Transplant. 1990 Mar–Apr;9(2):142–143.