Imagine you’ve just heard a compelling presentation urging all ACR members to contribute to RheumPAC, the ACR’s political action committee. RheumPAC’s mission is to support politicians who support issues important to rheumatologists. You are impressed by the role RheumPAC has played in a number of issues you support. Just as you’re writing a check, you learn that contributions to RheumPAC may go to political candidates who not only support issues that promote rheumatology, but who also hold positions on issues (including abortion and the Affordable Care Act) you find objectionable. Will your contribution to RheumPAC in support of your patients and your profession also violate your personal ethics? If so, how do you resolve this conflict?

How Politics Works

As a volunteer for the ACR, I [Dr. Mundwiler] have had the privilege of serving on both the Government Affairs Committee (GAC) and the Committee on Ethics and Conflict of Interest. Serving first on the GAC certainly influenced my perspective. Before getting involved with this committee work, I was naively idealistic. I thought the political process would proceed in a logical and linear manner: We would generate ideas that would benefit rheumatology, share ideas with politicians and staff, and watch our ideas be transformed into action.

I quickly came to understand, however, that the process was less direct and not necessarily based on our priorities. Instead of a process based on the merits of our ideas, I was confronted by a process whose chief goal is to maximize time with politicians and staff. The actual process is anything but logical and linear: We hope they notice and consider our ideas, hope that they remember our recommendations, hope that they have at least an understanding of what rheumatologists do and, ultimately, hope that what we find important influences legislation.

Those of us who have chosen to serve in a political capacity have to maintain faith that our efforts will one day make a positive change, all the while knowing that a lot of our efforts may not. The only predictable result is that a lack of participation with legislators and other government leaders will lead them to pay little or no attention to issues important to rheumatologists.This result may come with significant detriment to our patients and to us.

Overlapping Goals

There are several ways to generate exposure to the issues rheumatologists support. I found, however, that the quality time and exposure—where relationships are forged and personal connections are made regarding our issues—were at fundraisers. My epiphany was understanding that advocates and politicians actually have some overlapping goals. Advocates generate and use funds to help gain awareness for their issues; elected officials have to generate and spend considerable resources to gain exposure, communicate their message and campaign. Regarding these goals, both advocates and politicians also vocalize a similar ethical struggle. Both would rather be judged on the merit of their actions than on their ability to generate funds. The system, however, clearly rewards fundraising.

Ethically, it’s easy to see the conflict. The system places a premium on money generated in a way that is often independent of the goal of improving the lives of constituents, including our patients. Unfortunately, if we defer participation in the political process until it’s overhauled to a more ethically comfortable state, our profession and our patients may suffer.

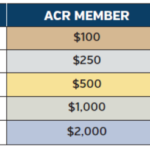

To encourage the ACR membership to participate politically, RheumPAC provides a resource to use funds from member donations to access fundraising events. A committee of volunteer rheumatologists determines who to support based on the legislator’s record of supporting rheumatology. Any ACR member can recommend an elected official for consideration.

Success Stories

The ACR, with the aid of relationships built through RheumPAC, was recently able to influence the repeal of the Sustainable Growth Rate (SGR) formula for physician reimbursement under Medicare, delay ICD-10 implementation and have the implementation of ICD-10 occur under more favorable conditions.1

Current Government Affairs Committee Chair William Harvey, MD, was given the opportunity to testify on behalf of legislation we drafted, the Patients’ Access to Treatment Act (HR 1600).2

Across Party Lines

Although success has been achieved, the proportion of ACR members contributing to RheumPAC is relatively low. At a 3.8% member participation rate and $225,000 contributed over the two-year 2014 election cycle, our participation is lower than many other specialties, including Orthopedic Surgery (21% participation, $2,181,500 contributed) and Family Medicine (6% participation, $757,000 contributed).1,3,4,5,6

While serving on the GAC, I found it hard to understand why the percentage of rheumatologists making at least a nominal donation remained small. When I moved from the GAC and shared this concern with the members of the Committee on Ethics and Conflict of Interest, reasons for low participation became clear. I realized the individual decision to donate to politicians, even indirectly through RheumPAC, is ethically complicated. Even if a politician supports rheumatologists’ concerns without reservation, the same politician could support a position that is in direct opposition to what an individual ACR member finds important in areas outside of rheumatology.

For RheumPAC, the primary determining factor is a candidate’s views and actions pertaining to rheumatology. Because major differences of opinion on high-profile issues often exist along party lines, RheumPAC has given its funds as equally as possible to Democrats and Republicans.7

The AMA’s code of ethics states that “physicians have a responsibility to work for the reform of, and to press for the proper administration of, laws that are related to health care. Physicians should keep themselves well informed as to current political questions regarding needed and proposed changes to laws concerning such issues as access to health care, quality of health care services, scope of medical research, and promotion of public health.”8

Ideally, the meeting of this ethical responsibility would be based solely on merit. It’s generally agreed this ideal is not the essence of the current system. Candidates require money to be elected. Legislators become aware of issues through donations to their campaign. Although influence is difficult to measure, donations could have an effect at all phases of the legislative process.9 Given what RheumPAC has been able to help accomplish, both donating and not donating have ethical pitfalls.

Although the political system we have may not be ideal, it seems undeniable that professional organizations must “play the game”: They must contribute to candidates to gain access and to have a voice for issues too important to ignore. Regardless of how we choose to participate in legislative reform, we do have an ethical responsibility to our patients and profession to participate. R

Editor’s note: Comments or questions? Submit them to the Ethics Forum via e-mail at [email protected].

References

1. St.Clair EW. Rheumatologists advance issues through advocacy. The Rheumatologist. 2015 May;9(5):11–12.

2. Harvey WF. Testimony—Committee on Energy and Commerce, Subcommittee on Health. 2014, June 12.

3. American College of Rheumatology: Profile for 2014 election cycle. OpenSecrets.org: Center for Responsive Politics. www.opensecrets.org/ orgs/summary.php?id=D000023939.

4. American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons: Profile for 2014 election cycle. OpenSecrets.org: Center for Responsive Politics. www.opensecrets.org/orgs/summary. php?id=D000064468.

5. American Academy of Family Physicians: Profile for 2014 election cycle. OpenSecrets. org: Center for Responsive Politics. www.opensecrets.org/orgs/summary. php?id=D000023903.

6. American Academy of Family Physicians. FamMedPac. www.aafp.org/advocacy/donate/ fammedpac.html.

7. Worthing A. RheumPAC nuts & bolts. The Rheumatologist. 2015 May;9(5):20–22.

8. Opinion 9.012—Physicians’ political communications with patients and their families. AMA Code of Medical Ethics. 1999 June.

9. Powell LW. The influence of campaign contributions on legislative policy. The Forum. 2013 Oct;11(3):339–355.