PARIS, FRANCE—Cardiac effects in rheumatological disorders produce myriad serious considerations for rheumatologists, and a leading authority offered pearls for treatment and management in a scientific session at the Annual European Congress of Rheumatology (EULAR 2014) in June.

Myocarditis

Heart involvement in autoimmune disorders can present in a variety of ways, said Alida Caforio, MD, PhD, assistant professor of cardiological, thoracic and vascular sciences at the University of Padova in Italy, and the leading author of a 2013 position paper on myocarditis for the European Society of Cardiology Working Group on Myocardial and Pericardial Diseases.1

A primary problem is that myocarditis can evolve into dilated cardiomyopathy (DCM) or dilation of the left or both ventricles that’s not explained by abnormal loading conditions or coronary artery disease and is instead brought about by genetic, infectious or autoimmune factors. Endomyocardial fibrosis can also lead to DCM. Also, some patients can experience DCM because of toxic effects of antiinflammatory drugs or immunosuppressants.

Cardiomyopathy in cases that are noncardiac in origin has been poorly studied, largely because studies are often retrospective or observational studies, the managing physician may not have much cardiology experience and patients have not received a proper cardiological workup.

In patients with systemic sclerosis, cardiac involvement is a negative prognostic factor and is often caught too late. Once a cardiologist sees these patients, they often already have diastolic heart failure, for which there aren’t many good treatments, Dr. Caforio said.

She offered two contrasting cases of patients with Churg-Strauss syndrome, also known as eosinophilic granulomatosis with polyangiitis, which involves inflammation of the blood vessels. One patient with eosinophilic pancarditis developed DCM. The diagnosis came relatively early, but not early enough.2

“If we have a diagnosis once we have already thickened endocardium and a lot of fibrosis, then we’ve lost the battle,” Dr. Caforio said.

In the other case, a 22-year-old Churg-Strauss syndrome patient presented with acute myocarditis and cardiogenic shock, but was treated aggressively from a rheumatological and cardiological standpoint—with systemic corticosteroids, IV cyclophosphamide, an intra-aortic balloon pump and mechanical ventilation. The patient was discharged after 21 days and was asymptomatic a year later.3

“The key is early diagnosis,” Dr. Caforio said. “Once the cardiac involvement of acute myocarditis is present, then you have to be very aggressive, not just with steroids but also with immunosuppressants to try and prevent the fibrotic stage.”

Granulomatosis with polyangiitis is another uncommon disorder involving inflammation of the blood vessels. There are good remission reduction treatment protocols, Dr. Caforio said, but even then there may be myocardial involvement requiring a pacemaker. She said it’s important to get accurate cardiac imaging because if there’s cardiac involvement, induction therapy might be difficult.

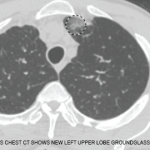

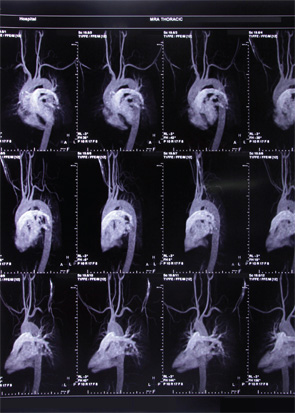

Cardiac MRI

Sven Plein, MD, professor of cardiology at the University of Leeds, reviewed the role of cardiac magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) in assessing the cardiovascular effects of chronic inflammatory conditions. Dr. Plein, who has studied the topic extensively, said that MRI offers “unique opportunities for imaging of the heart,” but also highlighted potential pitfalls.

In general, cardiac MRI is very accurate, with high reproducibility and consistent image quality, but as with any technique, expertise is needed to acquire and interpret the images correctly. In the published literature, this has not always been the case, as he demonstrated with several example images.

“Radiologists sometimes feel that cardiac assessment is more difficult than assessment of other organs, and cardiologists feel like it’s technically a challenging modality compared to echocardiography, for example,” he said. However, with appropriate training, cardiac MRI is no more challenging than other imaging.

Also, the availability of the technology varies widely. For example, there are more than 60 centers in the United Kingdom offering cardiac MRI, and similar numbers can be found in other European countries, but there are also countries in Europe with “only a handful” of centers.

He said cardiac MRI can be done in any hospital with MRI equipment—it just requires some additional software and hardware. But, he added, “that doesn’t get around the training issues. And those will take time, especially when there are political issues between radiology and cardiology over access to the scanners.” Ideally, the two specialties would collaborate.

Cardiac MRI in SLE

In a related study presented during the session, Sophie Mavrogeni, MD, a cardiologist with the Onassis Cardiac Surgery Center in Athens, presented findings showing the value of using cardiac MRI in assessing the heart involvement in systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) patients.

A total of 32 patients with new-onset heart failure in Class I or Class II—who were an average age of 29, and 29 of whom were women—were consecutively evaluated with cardiac MRI. The evaluation included left-ventricular function, short-tau inversion recovery and late gadolinium enhanced (LGE) images.

Researchers saw signs of acute myocarditis in five of the patients, dilated cardiomyopathy in five others, myocardial infarction in 11, vasculitis in nine and Libman-Sacks endocarditis in two. They found no mixed pathologies in any of the patients.

They also found that the presence of LGE, denoting myocardial fibrosis, correlated significantly with longer disease duration, higher erythrocyte sedimentation rate and the presence of antiphospholipid antibodies, Dr. Mavrogeni said.

Cardiac MRI might “facilitate the differential diagnosis and patients’ risk stratification,” she said.

Thomas R. Collins is a freelance medical writer based in Florida.

References

- Caforio AL, Pankuweit S, Arbustini E, et al. Current state of knowledge on aetiology, diagnosis, management, and therapy of myocarditis: A position statement of the European Society of Cardiology Working Group on Myocardial and Pericardial Diseases. Eur Heart J. 2013 Sep;34(33):2636–2648, 2648a–2648d.

- Terasaki F, Hayashi T, Hirota Y, et al. Evolution to dilated cardiomyopathy from acute eosinophilic pancarditis in Churg-Strauss syndrome. Heart Vessels. 1997;12(1):43–48.

- Courand PY, Croisille P, Khouatra C, et al. Churg-Strauss syndrome presenting with acute myocarditis and cardiogenic shock. Heart Lung Circ. 2012 Mar;21(3):178–181.