PARIS, FRANCE—Researchers are trying to drill down for a better understanding of the link between osteoarthritis and obesity—considered one of the most significant and probably one of the most preventable risk factors for the condition.

Andreea Ioan-Facsinay, PhD, assistant professor of rheumatology at Leiden University Medical Center in The Netherlands, discussed their work on the topic in a scientific session on the role of lipids in inflammation at the Annual European Congress of Rheumatology (EULAR 2014) in June.

D. Branch Moody, MD, professor of medicine in the Division of Rheumatology, Immunology and Allergy at Harvard Medical School, followed with a discussion of new insights into the function of T cells.

The Role of Obesity in Osteoarthritis

“How the association [of obesity] with osteoarthritis is mediated is not really known yet,” Dr. Ioan-Facsinay said. “However, what is interesting is that [obesity] is not only associated with osteoarthritis in the knee and in the hip and in the weight-bearing joints, but also with osteoarthritis of the hands.”

That implies that obesity is not just a problem of physical strain.

“The mechanisms that are involved in this association are not purely biomechanical, but probably have something to do with the systemic effects of obesity,” she said.

That might not be surprising considering that adipose tissue is a resource of soluble mediators—adipokines, cytokines, chemokines and lipids—and that these mediators can “assert a variety of functions,” Dr. Ioan-Facsinay said. The adipokine leptin, for example, has the important metabolic function of regulating appetite, but is also a potent immunomodulatory agent.

These mediators become different in the setting of obesity, Dr. Ioan-Facsinay said.

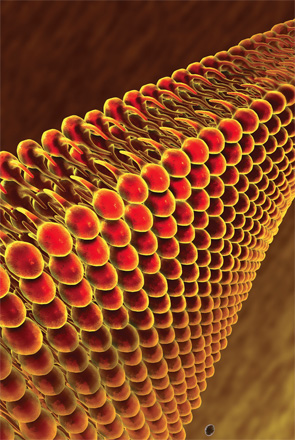

To untangle the role of obesity in osteoarthritis, investigators have focused on the knee, because it’s a part of the body where cartilage, bone and synovium are all close to fat tissue.

CD4-positive T cells, they found, produce increased levels of IFN-gamma when they’re activated in the presence of adipocyte-conditioned medium (ACM).

This effect, moreover, is seen mainly in the lipid fraction—much more than in the protein fraction—of ACM. Plus, they’ve found the effect is confined to fractions containing free fatty acids.

[Obesity] is not only associated with osteoarthritis in the knee & in the hip & in the weight-bearing joints, but also with osteoarthritis of the hands.

Researchers also found that fat cells can modulate cytokines by activated macrophages and that the effect seems to be antiinflammatory, which was somewhat surprising. This modulation fluctuated according to BMI: the higher the BMI, the more intense the effect.

The macrophage effect, as with T cells, was also mediated by fatty acids, and they’ve found that the fatty acids, oleic acid and linoleic acid, are secreted in higher amounts by adipocytes from people with higher BMIs.

“What is interesting is that fatty acids have a proinflammatory effect on T cells independently of their saturation grade, which is a bit contrary to the general view that saturated fatty acids would be proinflammatory and unsaturated would be antiinflammatory,” she said. “However, in the case of macrophages, you do see a difference between saturated and unsaturated fatty acids.”

Asked why she thinks those with high BMI have different properties, Dr. Ioan-Facsinay said it’s possible that the factor that mediates the effect (whether it’s fatty acids or something else) is simply secreted in higher amounts in people with a higher BMI.

She was also asked whether these mechanisms might be more prevalent in different types of OA—higher in synovium-driven OA and less so in bone-driven OA. She said she “can very well imagine” differences based on phenotype, but said, “I think it’s difficult to predict because in osteoarthritis you most probably have an interaction between cartilage, bone and synovium.”

T Cells

Dr. Moody discussed research at Harvard that has been widening the understanding of how T cells function.

For decades, the model for the understanding of T cells has been that they recognize an antigen through the alpha-beta receptor and bind to major histocompatibility complex (MHC) proteins. Building on the earliest studies of lipid antigens from the 1990s, researchers at Harvard in 2004 found that CD1a proteins present a lipopeptide from Mycobacterium tuberculosis.

“You wouldn’t think of this as a usual antigen for a human alpha-beta T cell clone,” Dr. Moody said. “We were very interested how a T cell receptor could recognize a molecule like this.”

Using a sophisticated method to quell autoreactivity, the researchers conducted experiments on a cohort of 17 people with no known disease, finding that all of them showed “demonstrable autoreactivity” to the CD1a protein, suggesting that CD1a autoreactive T cells are a “normal part of the human T cell repertoire,” Dr. Moody said.2 They then set out to determine their immunological function.

They recruited a small group of patients and looked at cytokine profiles. They found that many CD1a-autoreactive T cells homed to skin and produced interleukin 22 (IL-22).3

“We’re actively looking at the question of the general role of CD1a versus MHC in IL-22 response,” Dr. Moody said.

About a year and a half ago, the research team won a Rheumatology Research Foundation disease targeted research pilot grant for the start of a study involving rheumatoid arthritis subjects—the first time the cells have been studied in a human autoimmune disease, Dr. Moody said. Their hypothesis is that CD1a might be expressed on some sort of cell in the synovium, and that, possibly, CD1a autoreactive cells penetrate to the joint. They also wanted to look at the role of IL-22. They found CD1a is present in the synovium, although a more detailed phenotype is still being developed.

They also found that four of six adult RA subjects had demonstrably increased levels of IL-22 in the joint.

They’ve also looked at juvenile idiopathic arthritis (JIA) patients, and found “hugely elevated” levels of IL-22 in the joints of nine of the first 10 JIA patients. He stressed that this needs to be looked at more thoroughly, but that so far the data are “very encouraging” that this is a worthy line of inquiry.

“We don’t have the whole model yet,” Dr. Moody said. “This is very much a work in progress, but we have evidence for CD1a for CD1a autoreactive T cells and interleukin 22 in the joints of these patients.”

Thomas R. Collins is a freelance medical writer based in Florida.

References

- Ioan-Facsinay A, Kwekkeboom JC, Westhoff S, et al. Adipocyte-derived lipids modulate CD4+ T-cell function. Eur J Immunol. 2013 Jun;43(6):1578–1587.

- Moody DB, Young DC, Cheng TY, et al. T cell activation by lipopeptide antigens. Science. 2004 Jan 23;303(5657):527–531.

- de Jong A, Peña-Cruz V, Cheng TY, et al. CD1a-autoreactive T cells are a normal component of the human alphabeta T cell repertoire. Nat Immunol. 2010 Dec;11(12):1102–1109.