racorn/shutterstock.com

Management of rheumatoid arthritis (RA) is complex. The ever-expanding availability of new drugs requires that rheumatologists and patients constantly consider treatment strategies and targets aimed at both disease control and symptom relief while remaining cognizant of the increasing high cost of emerging medications. Given such complexity, guidelines to inform rheumatologists about the most recent developments on managing RA have been appearing every three years or so.

In 2015, the ACR published an updated guideline; previous versions were published in 2012 and 2008.1-3 Most recently, the European League Against Rheumatism (EULAR) released its RA guidelines updated in 2016; previous ones were published in 2013 and 2010.4-6 The frequency of these updated guidelines suggests the importance for rheumatologists to keep up with the fast pace of the evidence to ensure the many and new treatment options available are tailored to individual patients and offered to all patients. This is particularly important given the high cost of many of the agents, such as biologics, that limit their widespread use.

This is aptly stated in the 2016 EULAR guidelines: “Management recommendations on the approach to treating patients with RA have become increasingly useful in providing physicians, patients, payers, regulators and other healthcare suppliers with evidence-based guidance supported by the views of experts involved in many of these novel developments.”4

This article highlights key findings and recommendations from the most current EULAR RA guideline. Drawing on the most current evidence to date, the 2016 EULAR update continues to support treatment strategies and specific treatment recommendations found in previous EULAR and ACR guidelines. Both guidelines emphasize treat-to-target strategies aimed at disease control, along with symptom relief, and offer specific treatment recommendations to help patients achieve this goal. Importantly, they now highlight the need to achieve and maintain treatment control.

The following sections focus on specific, new evidence-based recommendations for first- and second-line treatments, as well as tapering patients off therapies once persistent remission is achieved.

Foundations for Treatment Decisions & Goals

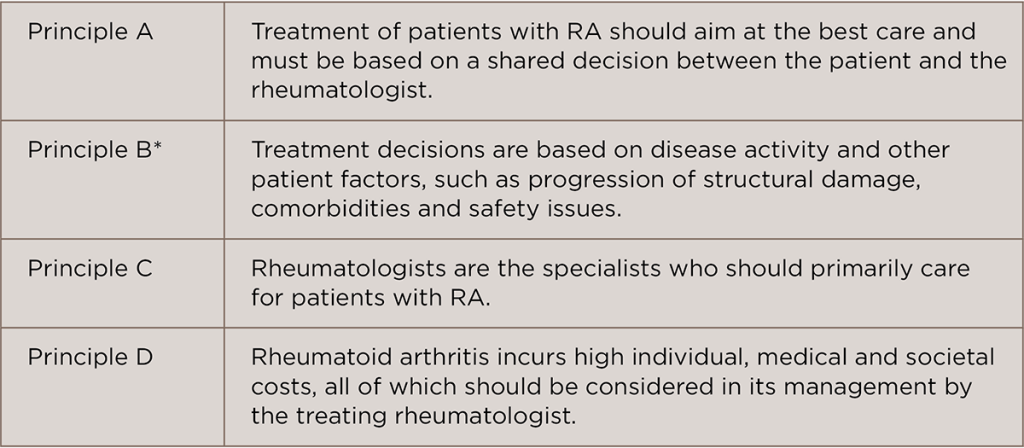

One change to the 2016 EULAR guidelines is the higher emphasis placed on basing treatment decisions not only on disease activity, but importantly, on such patient factors as comorbidities. This change is reflected in the four overarching principles that the guidelines provide (see Table 1). As noted in Table 1, principle B—Treatment decisions are based on disease activity and other patient factors, such as progression of structural damage, comorbidities and safety issues—moved from being a recommendation in the 2010 guideline to foundational in the 2016 guideline, reflecting the importance of considering comorbidities in treatment decisions.

(click for larger image)

TABLE 1: EULAR 2016 RA Guidelines: Overarching Principles4

*New principle added

Commenting on the guidelines, Vivian P. Bykerk, MD, director of the Inflammatory Arthritis Center, Hospital for Special Surgery, and an associate professor of the Weill Cornell Medical College, New York, highlighted that a significant conceptual change in the guideline is that the goals for therapy will need to be considered in light of any patients with comorbid conditions. “That is not to say that the goal of sustained disease control should not be aimed for, but that it is reasonable not to escalate therapies to try and achieve stringent disease control if it would not be safe to do so if a comorbid condition places the patient at greater risk for an adverse event,” she says.

Specific Treatment Recommendations

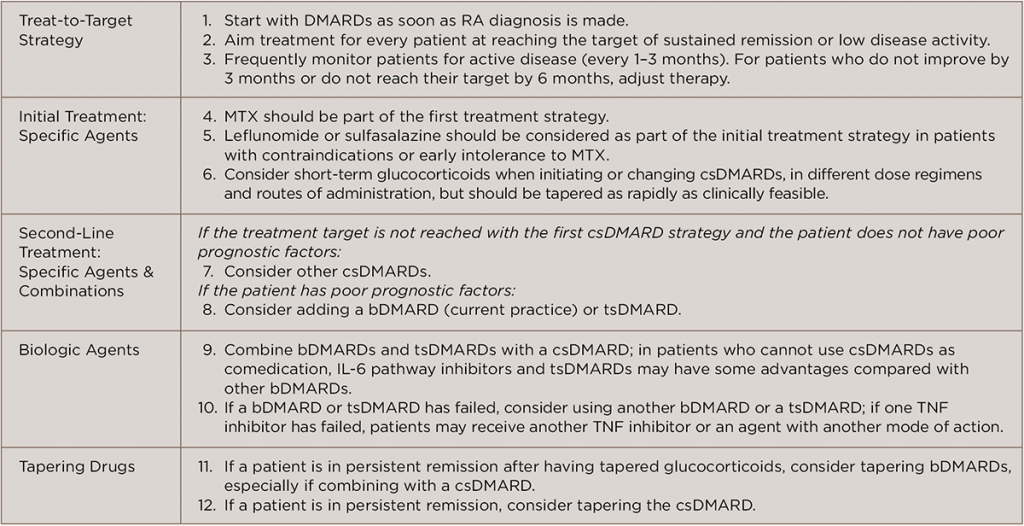

Similar to the previous guidelines, the 2016 recommendations are based on an overall treat-to-target strategy that begins with initiating effective disease-modifying anti-rheumatic drug (DMARD) therapy immediately following a diagnosis of RA, setting a treatment target goal, and assessing disease activity while trying to reach the target goal (see recommendations 1–3 in Table 2).

(click for larger image)

TABLE 2: EULAR 2016 RA Guidelines: Treatment Recommendations4

Glossary: DMARDs, disease-modifying anti-rheumatic drugs; RA, rheumatoid arthritis; MTX, methotrexate; csDMARDs, conventional synthetic DMARDs; bDMARD, biologic DMARD; tsDMARD, targeted synthetic DMARD; TNF inhibitor, tumor necrosis factor inhibitor

According to Dr. Bykerk, a key conceptual change in this guideline is to extend the goal of therapy to include the word sustained. “Thus, not only do we want a patient to achieve a target goal of remission, or if that is not possible then low disease activity, but we expect the patient to be regularly monitored and medication adjustments performed to maintain that target goal,” she says.

Other significant changes in this guideline from previous guidelines are new recommendations on the types of agents to use and when. One changed recommendation the lead author of the guidelines, Josef Smolen, MD, professor, Division of Rheumatology, Department of Medicine 3, Medical University of Vienna, Austria, highlights is the recommendation that initial therapy to treat treatment-naive patients can be with methotrexate (MTX) plus short-term glucocorticoids.

He also underscores a change in verbiage from “low-dose, short-term” to the current “short-term” to reflect data showing that a single intravenous dose of 250 mg glucocorticoids leads to excellent results. “Also, 30 mg prednisone daily, tapered rapidly, gives good outcomes,” he says.

Several guidelines have recommended using a combination of conventional synthetic DMARDs (csDMARDs), including MTX, as initial treatment. [See sidebar, below, for a description of the acronyms used to distinguish the varying types of DMARDs.] However, Dr. Smolen says current evidence also supports a strong recommendation for combining a csDMARD with glucocorticoids. He underscores that the data show no advantage of adding another csDMARD (e.g., sulfasalazine [SSZ] or leflunomide or SSZ plus hydroxychloroqauine), and that combinations of csDMARDs show more frequent adverse events than when combining MTX with a short course of glucocorticoids.

Dr. Smolen

“Some colleagues do not like the fact that we omitted combination csDMARDs,” says Dr. Smolen, “but we provide the evidence for doing this.”

Dr. Bykerk also notes that this recommendation was not without controversy and highlights “the need for more current studies of combination DMARDs, particularly in comparison with higher dose MTX and subcutaneous MTX.”

For second-line treatment for patients who do not reach their target goal of remission or low disease activity, the new guideline recommends stratification by risk factors of rapid damage progression. “If these risk factors are absent, another csDMARD strategy can be used,” he says.

However, for patients with poor prognostic factors, he says any biologic DMARD can be used, as well as a Janus kinase (JAK) inhibitor. The use of a JAK inhibitor as an alternative to a biologic DMARD in this context is now recommended on the basis of new long-term data on JAK inhibitors for second-line therapy, he says.

Of note is the recommendation for combining biologic DMARDs and JAK inhibitors with MTX or other csDMARDs, based on evidence showing that the combination of these agents appears generally more efficacious than monotherapies.

Dr. Smolen says this recommendation, too, may be controversial for some rheumatologists. “Some rheumatologists would have preferred that we recommend some biologics, such as tocilizumab and Jakinibs, for monotherapy,” he says. “But again, we have sufficient evidence that combination conveys better outcomes.”

As to the recommendation for tapering treatment for patients who achieve persistent remission, Dr. Bykerk emphasizes that the guidelines stress the importance of tapering slowly and following a “reverse treat to target” approach in which any reduction will still ensure no loss of disease control. “It is too early to be prescriptive as to what order therapies should be tapered,” she says. “The only exception to this was that steroid [use] should be the first therapy tapered and that their use, in fact, should always be considered short term.”

The ACR 2015 Guideline

The 2016 EULAR guideline and 2015 ACR guideline are based on similar treat-to-target treatment strategies.

According to Dr. Smolen, the two updates of the ACR and EULAR guidelines are the closest to date in terms of recommending treat-to-target strategies and recommending first-line treatment with combination MTX and glucocorticoids. Older treatment recommendations were to combine csDMARDs.

Points where they differ include the inclusion in the 2016 EULAR guidelines of not-yet-approved agents, sirukumab and sarilumab (although this latter drug has since been recommended for approval by the European Medicines Union), as well as baricitinib, which was recently licensed in Europe. The ACR guidelines differ as well in their recommendation of biologics as mono- or combination therapy.

Dr. Bykerk notes that the EULAR recommendations are more proscriptive than the ACR guideline about the early use of csDMARDs, with MTX as the specific agent to use for first-line treatment, as well as the use of another csDMARD (specifically SSZ or leflunomide) if MTX is not tolerated.

“Importantly, [EULAR] will not fully endorse that ‘triple’ DMARD or any specific combination of csDMARDs should be mandatory,” she says. “However, they also recommend concomitant csDMARDs should be used with bDMARDs, except in the cases of tocilizumab and tofacitinib.”

Dr. Smolen points out that the guideline does recommend concomitant use of csDMARDs for all bDMARDs and recommends monotherapy, preferably IL-6 or JAK inhibitors, only if all csDMARDs are contraindicated.

Mary Beth Nierengarten is a freelance medical journalist based in Minneapolis.

Nomenclature for Disease-Modifying Anti-Rheumatic Drugs

The 2016 EULAR guidelines use a set of acronyms to denote the varying classes of disease-modifying anti-rheumatic drugs (DMARDs) now available. Dr. Bykerk recommends the wide adoption of these acronyms in articles going forward to enable rapid understanding of what specific DMARDs are being discussed. She also suggests subclassifying biologic DMARDs.

Specific acronyms for DMARDs:

- Conventional synthetic DMARDs (csDMARDs): This group includes methotrexate, leflunomide, sulfasalazine and hydroxychloroquine;

- Targeted synthetic DMARDs (tsDMARDs): This group includes tofacitinib and baricitinib; and

- Biologic DMARDs (bDMARDs):

- Biological originator DMARDs (boDMARDs); and

- Biosimilar DMARDs (bsDMARDs).

References

- Singh JA, Saag, KG, Bridges SL Jr., et al. 2015 American College of Rheumatology guideline for the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken). 2016 Jan;68(1):1–25.

- Singh JA, Furst DE, Bharat A, et al. 2012 Update of the 2008 American College of Rheumatology recommendations for the use of disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs and biologic agents in the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken). 2012 May;64(5):625–639.

- Saag KG, Teng GG, Patkar NM, et al. American College of Rheumatology 2008 recommendations for the use of nonbiologic and biologic disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs in rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 2008 Jun 15;59(6):762–784.

- Smolen JS, Landewé R, Bijlsma J, et al. EULAR recommendations for the management of rheumatoid arthritis with synthetic and biological disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs: 2016 update. Ann Rheum Dis. 2017 Jun;76(6):960–977.

- Smolen JS, Landewé R, Breedveld FC, et al. EULAR recommendation for the management of rheumatoid arthritis with synthetic and biological disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs: 2013 update. Ann Rheum Dis. 2014 Mar;73(3):492–509.

- Smolen JS, Landewé R, Breedveld FC, et al. EULAR recommendations for the management of rheumatoid arthritis with synthetic and biological diease-modifying antirheumatic drugs. Ann Rheum Dis. 2010 Jun;69(6):964–975.