SAN DIEGO—In an elegant and engaging presentation that used concepts from evolutionary medicine to provide novel insights into the pathophysiology of chronic inflammatory diseases, Rainer H. Straub, MD, professor of medicine in the lab of experimental rheumatology and neuroendocrine immunology in the department of internal medicine, division of rheumatology, at University Hospital in Regensburg, Germany, honored the memory of Philip S. Hench, MD, during his delivery of the 2013 Hench Lecture at the at the 2013 ACR/ARHP Annual Meeting. [Editor’s Note: This session was recorded and is available via ACR SessionSelect at www.rheumatology.org.] He showed how the scientific mind works through a hypothesis to arrive at some theoretical possibilities on the mysterious workings of the human body in chronic inflammation.

“In a thoughtful and integrative approach, Dr. Straub advanced the hypothesis that the consequences to the body of chronic inflammatory disease result from prolonged energy requirements of an activated immune system,” said Eric Matteson, MD, chair of the department of rheumatology and professor of medicine at the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minn., who moderated the session. “By integrating new insights with studies of metabolism, neuroendocrinology, and immunology, the new model explains the sometimes baffling symptomatology of autoimmune disease.”

What does the hypothesis or new model proposed by Dr. Straub contribute to an understanding of the pathophysiology of chronic inflammatory diseases? The following are some of the steps he walked participants through to explain this new model.

Etiology of Chronic Inflammatory Diseases: Systemic Response

Dr. Straub introduced first the idea of a systemic response as a potential etiological factor in chronic inflammatory diseases (CIDs). Although classic etiological factors of CIDs focus on local inflammation (e.g., the immune system), with the underlying understanding that the dangerous molecules involved in local inflammation remain local and don’t get into the body’s system, Dr. Straub said that inflammatory factors can spill over to the central nervous system or to endocrine glands either through cytokines, such as interleukin (IL) 6 in circulation, or via sensory nerve fibers and activate the sympathetic nervous system and the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis while shutting down other pathways (e.g., gonadal axis). He provided examples to show that there is crosstalk between local inflammation in tissue and the central nervous system and endocrine organs, and that this crosstalk has influence but is relatively nonspecific (i.e., it is observed in many CIDs).

In answering why there is a systemic response, he focused on the high level of energy consumed when the immune system is activated, indicating that inflammation needs a lot of energy-rich fuels. Regulation of energy, he said, depends on two super systems in the body—the brain and muscles that consume energy during the day and the immune system that consumes energy primarily at night.

Local inflammation, he said, needs mainly local fuels, and systemic energy is not needed. Sometimes, however, cytokines, activated immune cells, and sensory nervous signals spill over and induce an energy appeal reaction that enforces a systemic energy supply.

Local inflammation needs mainly local fuels, and systemic energy is not needed. Sometimes, however, cytokines, activated immune cells, and sensory nervous signals spill over and induce an energy appeal reaction that enforces a systemic energy supply.

Analyzing the Systemic Response

Using concepts from evolutionary medicine, he then introduced the idea that the neuroendocrine immune network has been positively selected to serve short-lived inflammation (e.g., infectious diseases). He rejected the notion that genes have been positively selected for CIDs over time and emphasized that the genes linked to rheumatic diseases (such as HLA DR4) are for short-lived inflammatory reactions (for example, to overcome Dengue hemorrhagic fever).

According to Dr. Straub’s theory, interactions of the immune, nervous, and endocrine systems are necessary for energy and volume regulation and are positively selected for acute short-lived inflammation.

In systemic disease sequelae of CIDs, he said, important adaptive programs are switched on to support acute, but not chronic, energy-consuming inflammation, and this has desolate consequences for the rest of the body.

“When inflammation occurs, the immune system is demanding energy-rich fuels and stops the other supersystem. This demand reaction has been positively selected to overcome infectious diseases,” he said. “Long-term use of the demand reaction leads to unwanted disease sequelae in chronically inflamed patients.”

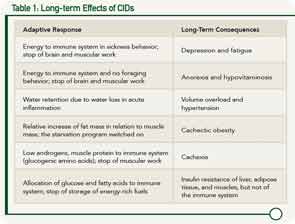

He walked participants through a number of examples to illustrate these desolate consequences or disease sequelae of CIDs when adaptive programs are switched on over the long term (see Table 1).

Energy Demand: The Unifying Concept

These examples of disease sequelae of CIDs highlight the central theme of Dr. Straub’s hypothesis. “Energy homeostasis is the common denominator of the systemic disease sequelae in chronic inflammatory disease,” he said.

He ended his talk by highlighting data that show that even slight increases in serum IL-6 elevates energy expenditure and starts the energy appeal reaction in humans, and that gradual increases in serum IL-6 occur naturally as people age. In people with chronic inflammatory diseases, however, this gradual increase is escalated and results in accelerated aging and premature age-related diseases.

For Dr. Straub, the new model or hypothesis emphasizes the importance of inflammation and controlling it. His key message to clinicians: “Keep inflammation as low as possible in order to stop the energy-demanding immune system,” he said, with the desired aim to achieve a C-reactive protein target in the normal range.

“Although some disease sequelae are long-standing in nature, many disease sequelae will be removed when controlling inflammation,” he emphasized, saying that clinicians should “try to overcome the inflammation as soon as possible in order to prevent possible long-term imprinting of disease sequelae due to structural changes in involved organs.”

Mary Beth Nierengarten is a freelance medical journalist based in St. Paul, Minn.

Key Resources

- Straub RH. Evolutionary medicine and chronic inflammatory state—known and new concepts in pathophysiology. J Mol Med. 2012;90:523-534.

- Straub RH, Cutolo M, Buttgereit F, Pongratz G. Energy regulation and neuroendocrine-immune control in chronic inflammatory diseases. J Intern Med. 2010;267:543-560.

- Straub RH, Besedovsky HO. Integrated evolutionary, immunological, and neuroendocrine framework for the pathogenesis of chronic disabling inflammatory diseases. FASEB J. 2003;17:2176-2183.