The effects of knee osteoarthritis (OA) on an individual can go far beyond having to live with a stiff and painful knee. People with symptomatic knee OA are less active than their peers and are at increased risk for inactivity-related diseases such as hypertension, diabetes, obesity, and cardiovascular disease. Inactivity produces general deconditioning as well as increased pain, weakness, stiffness, and functional loss. Knee OA is a major cause of disability, and prolonged inactivity adds to the loss. Fortunately, many of the sequelae of knee OA are modifiable through exercise.

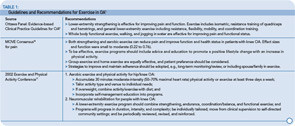

As shown in Table 1, guidelines for the management of hip and knee OA consistently recommend exercise as an integral component of management.1 Both strengthening and aerobic exercises show positive results in clinical trials. Outcomes of exercise include decreased pain and improved function as well as increased strength, range of motion, and cardiovascular health. It appears that moderate exercise does not increase the incidence or speed progression of the disease and there is emerging evidence that regular moderate exercise can reduce effusions and improve the content of glycosoaminoglycans in cartilage, an important biochemical indicator of its viscoelastic properties.2,3 Aerobic walking, stationary cycling, strengthening, and water exercise are all safe and effective for patients with OA. Whether the exercise is performed at home, in a clinic, or in a group setting, benefits are clear, with generally moderate effect sizes in this diverse population.

Despite the well-documented evidence for the numerous benefits of regular exercise for people with knee OA, most people with this condition are nevertheless inactive and receive little information or support from physicians on how to be physically active. There are understandable reasons for this inattention to a known, effective intervention. Pain usually prompts the doctor visit and immediate treatment focuses on pharmacologic pain relief. Time and resources to prescribe appropriate exercise and follow-up are limited in most clinical encounters. Furthermore, the general nature of exercise recommendations in medical guidelines, the range of possible activities, and the diversity in this patient population make it difficult for the physician to know what to recommend. Although well-intentioned, the suggestion to “start getting some exercise” is not particularly helpful or often followed.

However, we know that physicians and clinic staff can influence patients to change beliefs and behaviors in areas such as smoking cessation, diet, and exercise.4 With knowledge and planning, it is possible—within the constraints and staffing of the clinic visit—to establish procedures to help patients become more active and exercise successfully. Here is a useful framework for how to: 1) promote awareness of the importance of exercise at the time of the office visit; 2) offer a simple home exercise program; 3) use community-based exercise and self-management resources; and 4) identify patients to refer to physical therapy.

Promote Exercise at the Office Visit

In general, people who receive advice from their physician to exercise are more likely to exercise than people who do not. People with arthritis who exercise often begin because a physician suggested it and provided information. In a study of rheumatologists and patients with rheumatoid arthritis, only 58% of the physicians discussed exercise with their patients, and most physicians reported that they did not have the time or feel comfortable recommending exercise.5 To follow current management guidelines for knee OA, exercise should be discussed at every office visit. It is up to the physician to start the discussion.