ME/CFS

Dr. Komaroff

Another disorder rheumatologists should look out for is myalgic encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome (ME/CFS), said Anthony Komaroff, AB, MD, MA (Hon), senior physician, Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston, and Steven P. Simcox, Patrick A. Clifford and James H. Higby Distinguished Professor of Medicine, Harvard Medical School, Boston. ME/CFS is defined as a substantial impairment in the ability to function for more than six months, along with a new, profound fatigue not relieved by rest, malaise after exertion, unrefreshing sleep, cognitive impairment and/or orthostatic intolerance. People with ME/CFS tend to have scores on tender point exams halfway between normal and what appears in fibromyalgia. The condition often starts with an infectious illness.

Many features of ME/CFS overlap with fibromyalgia, including fatigue and headaches. But in ME/CFS, several abnormalities of the central nervous system (CNS) tend to appear, such as neuroendocrine dysfunction, cognition problems and magnetic resonance imaging abnormalities. ME/CFS is also marked by immune activation, including elevated cytokine levels, increased circulating activated CD8-positive cells and autoantibodies against CNS antigens.

Metabolic studies have found a general downregulation of metabolic products as well as impairment of energy metabolism, Dr. Komaroff said.1

An emerging theory posits ME/CFS is the “sickness symptoms hypothesis,” in which during acute illness, a group of neurons called the fatigue nucleus orchestrates a reduction in energy consuming activities to preserve energy stores to fight the illness. One likely trigger of the fatigue nucleus is neuroinflammation that continues even though the inciting antigen is wiped out. Alternatively, in some people, the activated fatigue nucleus gets stuck in the on position, causing sickness symptoms to continue, Dr. Komaroff said.

“There remain many important unanswered questions in this illness, but the increasing interest and support from NIH and CDC in studying it, I hope, [will] provide some more fundamental answers in the coming years,” he said.

MCAS

Dr. Schwartz

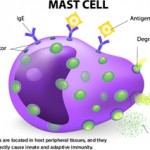

A mast cell activation syndrome (MCAS) diagnosis includes clinical presentation of systemic anaphylaxis, elevated mast cell biomarkers, a response to anti-mast cell-mediator or activation therapies, and possibly, inherited or acquired genetic traits, said Lawrence Schwartz, MD, PhD, the Charles and Evelyn Thomas Professor of Medicine and chair of the Division of Rheumatology, Allergy and Immunology, Virginia Commonwealth University, Richmond.

Systemic anaphylaxis involves a rapid onset of illness involving two or more of the following systems: skin, gastrointestinal, respiratory or cardiovascular. Its lifetime prevalence among adults ranges from 2–8%, according to phone surveys, so there is a need for biomarkers for precise diagnosis, said Dr. Schwartz.

During systemic anaphylaxis, tryptase (which accounts for 10–20% of the entire protein in a mast cell, but with no pharmacotherapy that blocks its production) has a half-life of about two hours in circulation after its secretion by activated mast cells. This is longer than other commercially available biomarkers, so it can be useful in diagnosing MCAS. But a baseline level must be available, because a clinically significant rise in acute tryptase levels is defined as 1.2 times the baseline level, plus 2 ng/mL.

“An acute tryptase level by itself isn’t helpful,” Dr. Schwartz said.

Somatic gain-of-function mutations of the c-kit gene or an inherited genetic trait underlie many MCAS cases, he said. Increased copies of the protein coding gene TPSAB1, when that gene encodes alpha-tryptase, can enhance alpha-tryptase expression, known as hereditary alpha-tryptasemia.2

Dr. Schwartz added that cases without a known cause could involve dysregulation of other pathways involved in mast cell activation.