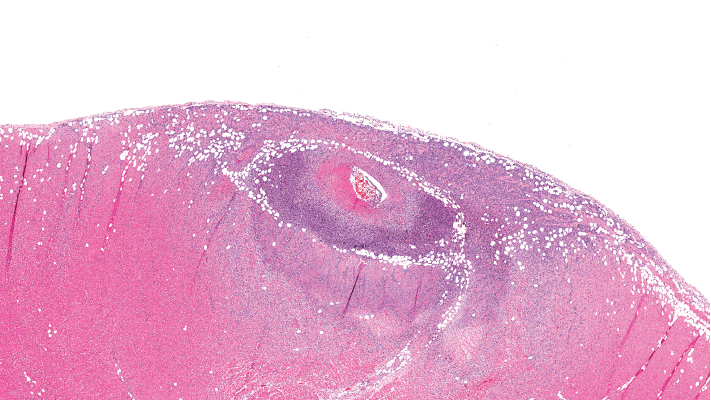

This image depicts severe arteritis of the coronary artery with inflammation and thrombosis, with extension into the myocardium.

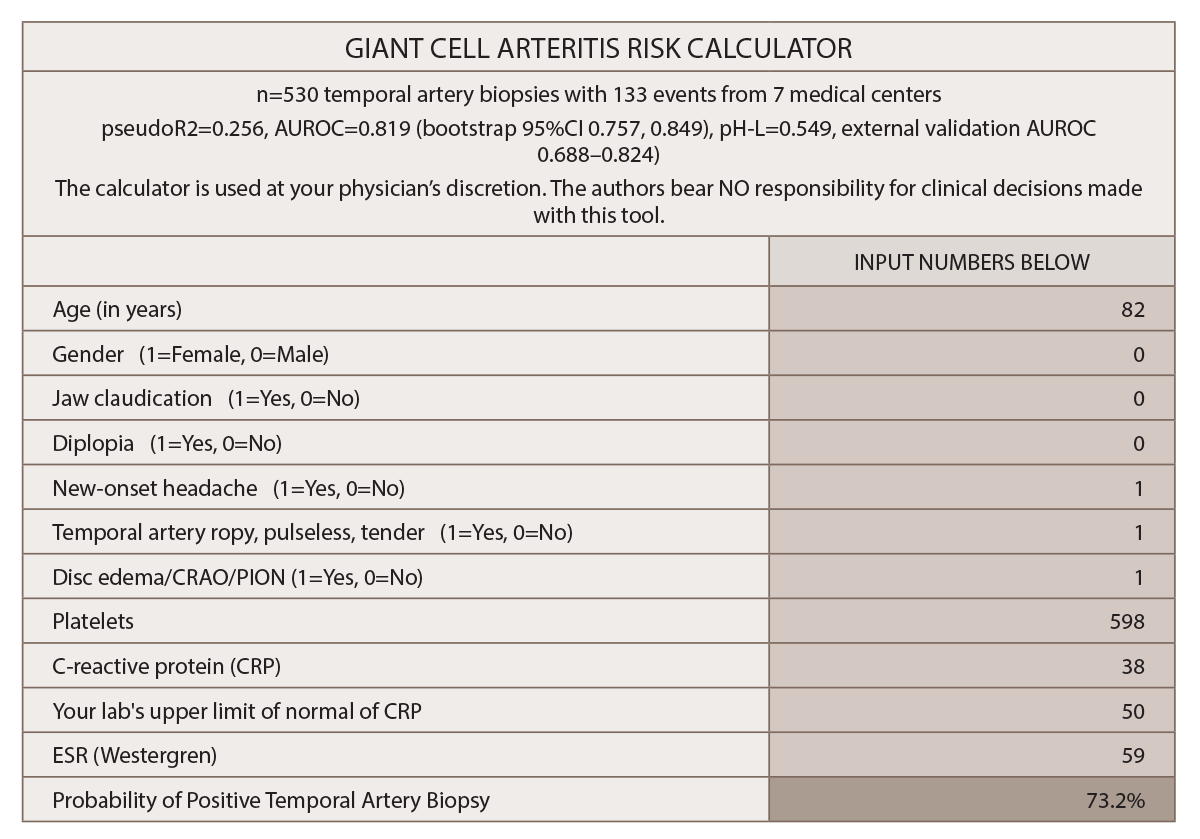

A proposed model to predict the risk of giant cell arteritis (GCA) prior to a temporal artery biopsy could help triage patients and guide decision making about the need for biopsy or monitoring (see Figure 1).

There’s no specific biomarker for GCA, and GCA can be a “diagnostic conundrum, especially when it presents in an occult or atypical fashion,” according to the researchers who published the development and validation data on their multivariable prediction model in a recent issue of Clinical Ophthalmology.1

Edsel Ing, MD, MPH, an ophthalmologist at Michael Garron Hospital and associate professor at the University of Toronto, and his colleagues note that even though several clinical prediction rules in the diagnosis and management of patients with suspected GCA exist, few were developed using more than 500 temporal artery biopsies or 100 biopsy-positive GCA cases, and few included external validation. The group’s research was compliant with the TRIPOD Initiative, a set of recommendations for reporting research that develops, validates or updates a prediction model so that bias risk and potential usefulness of the model can be adequately assessed.

The dearth of validated, TRIPOD-compliant prediction models for GCA that predict the risk prior to temporal artery biopsy prompted the research, Dr. Ing says. “GCA can be very difficult to diagnose without a biopsy. Sometimes, we look at blood tests, but how significant are the serology results compared with the patient’s symptoms? If a 60-year-old patient has a new-onset headache but blood tests are normal, compared to a 65-year-old patient with abnormal serology but no headache, determining the relative risk for GCA is problematic.”

Objective vs. Subjective Variables

Dr. Ing’s research analyzed the predictive value of objective and subjective variables that could potentially predict which patients are at higher risk of having biopsy-proven GCA. The investigators performed a retrospective review of case records of consecutive adult patients undergoing temporal artery biopsy for suspected GCA at seven secondary/tertiary care referral clinics. The researchers retrieved records from four medical centers in Canada, the U.S. and Switzerland. Forty-eight percent of the patients had been referred by ophthalmologists, and the rest by rheumatologists, internal medicine physicians or primary care centers.

All patients undergoing temporary artery biopsy for suspected GCA within two weeks of steroid initiation were eligible for the study. The pathologic diagnosis was considered the final diagnosis. Healed arteritis was considered positive for GCA in the research, and any case with an indeterminate pathologic diagnosis was considered negative for GCA. A review of 688 patients undergoing temporal artery biopsy yielded 530 cases with complete data. From the cohort of 530 cases, negative temporal artery biopsy results were reported for 397 patients and positive biopsies for 133 patients. The researchers performed multiple imputation for the missing data.

The a priori variables chosen for the prediction model included age, gender, jaw claudication, new-onset headache, clinical temporal artery abnormality, ischemic vision loss, diplopia, platelet level, erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) and C-reactive protein (CRP). Only cases that had details on each of those variables were included in the analysis. According to Dr. Ing, one of the most difficult elements involved was finding patients with complete blood work results (i.e., ESR, CRP, platelets) who had had the temporal artery biopsy prior to 14 days of glucocorticoid therapy.

‘The prediction model provides a numeric final output probability of biopsy-proven GCA.’ —Dr. Ing

Statistically Significant Predictors

The data analysis found the statistically significant predictors of a positive temporal artery biopsy included age, jaw claudication, ischemic vision loss, higher platelet level and log CRP. The variables that were not statistically significant predictors included ESR, gender, new-onset headache and temporal artery abnormality.

Dr. Ing says the group found no surprises among the predictive variables. “It was interesting, however, to find that thrombocytosis, or elevated platelets, was such a strong predictor,” he says. “In our study, the log transform of the CRP divided by its upper limit of normal was a bigger predictor for GCA than the raw CRP.” In addition, he says, “[Because] ischemic vision loss (i.e., anterior ischemic optic neuropathy, posterior ischemic optic neuropathy, central retinal artery occlusion) was a statistically significant predictor for biopsy-proven GCA, this may explain why binocular diplopia was not.”

(click for larger image) Figure 1: Multivariable Prediction Model for Suspected Giant Cell Arteritis: Development & Validation

* Gender and diplopia were NOT predictive for GCA in this study.

(click for larger image) Source: Clinical Ophthalmology by Society for Clinical Ophthalmology (Great Britain). Reproduced with permission of Dove Medical Press Limited in The Rheumatologist via Copyright Clearance Center.

“The prediction model provides a numeric final output probability of biopsy-proven GCA so patients and their clinicians can objectively decide whether to initiate glucocorticoid therapy and/or undergo a temporal artery biopsy,” Dr. Ing says. The final model assigns a probability of a positive temporal artery biopsy based on the following variables: age, gender, jaw claudication, diplopia, new-onset headache, temporal artery abnormality, funduscopic abnormality, thrombocytosis, ESR and CRP.

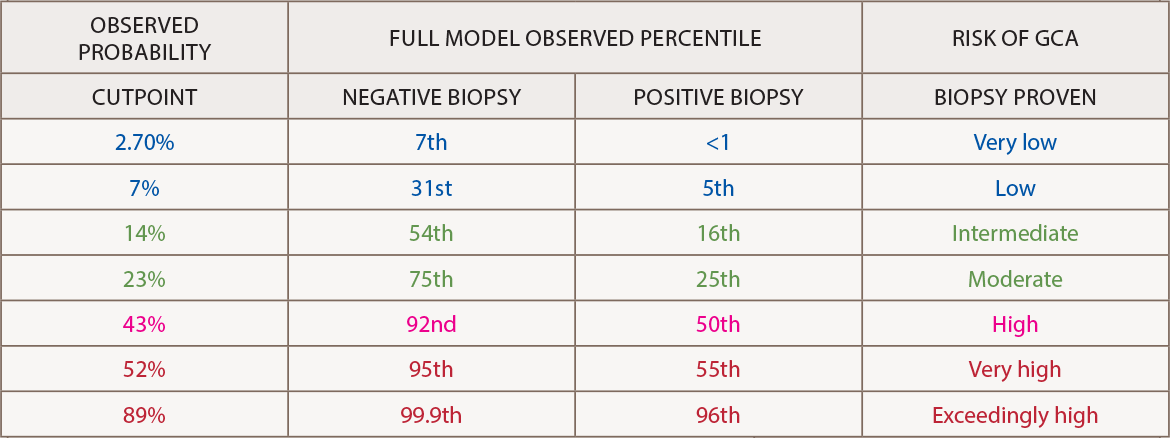

The output calculator should be interpreted in light of the cutpoint table. A nomogram for the 10-variable prediction model “allows clinicians without a formal training in statistics to graphically understand how the odds ratios and confidence intervals of each predictor contributes to the final probability for GCA on logistic regression,” he says.2

Their research continues, with plans to expand their patient database to 1,000 patients and compare logistic regression with a neural network analysis. He says he hopes other investigators will incorporate tests such as ultrasound or dynamic contour tonometry with prediction rule.3

Temporal artery biopsy remains the criterion standard for diagnosis for GCA, Dr. Ing says, but there are some problems with it. “You can have some false negatives, [it’s] time consuming [and] uncomfortable for patients, and surgeons often find it difficult to schedule the biopsy within the two-week glucocorticoid window.”

The model’s GCA calculator is meant to objectify decision making by the patient and doctor. The higher the score, the more likely the patient has GCA and should be treated with glucocorticoids. Patients with a score below 7% may have low risk of GCA and perhaps can be monitored rather than undergoing a biopsy, he explains.

“I was previously unable to provide patients an objective metric for their risk of GCA. The numeric output of the prediction calculator renders objectivity to clinical decision making and allows the physician and patient to better decide what should be done. With risk scores higher than 10–15%, clinicians might be inclined to recommend glucocorticoid treatment and more definitive investigations such as biopsy,” Dr. Ing says.

Possible Study Problems

Note: The authors acknowledged in their paper that it has some limitations and potential weaknesses. In their introduction, they emphasized that the 1990 ACR classification criteria for GCA were not intended for diagnosis. They also said, “Our study had some limitations, which includes its retrospective nature with missing data, the constraint to BPGCA, and misclassification rate.” They also acknowledged that “the limited size of our external validation (EV) sets is a potential weakness.”

According to Peter Grayson, MD, head of the Vasculitis Translational Research Program at the National Institute of Arthritis & Musculoskeletal & Skin Diseases, the investigators should be commended for “going to great lengths to be methodologically rigorous in data analysis and use of statistical methods to account for potential flaws in the dataset, such as missing data.”

The large sample size, internal and external validation techniques, and online risk calculator are good features of the work, says Dr. Grayson. However, some problems with the cohort “cannot be overcome by statistical approaches,” he says. “Notably, a retrospective study design can introduce sources of bias, including selection bias of study subjects and bias due to non-standardized data collection practices across the cohort. A prospective study design in a large independent cohort would be important to validate the findings.”

Kenneth J. Warrington, MD, professor of medicine at the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minn, says the researchers’ decision to consider healed arteritis as positive for GCA is a problem. “That is a very controversial topic,” he says. “The definition of what is called healed arteritis is not clear, and there is debate among pathologists as to what that represents. It may be a very nonspecific finding that can even be seen in a normal elderly patient. It is a nonspecific pathologic description.

“If I were designing the study, I would not consider healed arteritis as positive for GCA,” Dr. Warrington says.

Invalid Comparisons

The retrospective research for the prediction model used logistic regression to compare the model with the 1990 American College of Rheumatology criteria for disease classification.4 Dr. Ing and colleagues reported that the prediction model outperformed the ACR criteria.

Dr. Grayson says the comparison isn’t valid. The criteria were not intended for diagnosis, but instead were intended to help classify the disease relative to other forms of vasculitis. In addition, the reported model only predicts temporal artery biopsy results rather than diagnoses GCA, another reason a comparison is invalid, he says.

Further, according to Leonard Calabrese, DO, professor of medicine at the Cleveland Clinic Lerner College of Medicine of Case Western Reserve University in Cleveland, Ohio, the ACR criteria are now considered “out of date and out of touch with our current understanding of GCA.” Dr. Calabrese was one of the authors of the 1990 criteria.

There are efforts underway to update the classification criteria, according to Dr. Warrington. Updates are needed because the 1990 criteria do not include CRP, which is now a widely used marker of inflammation, and the criteria don’t incorporate imaging either.

So Is It a Good Tool?

The rheumatologists contacted for this article pondered whether the researchers’ prediction model moves the field forward as a type of diagnostic tool. “The authors are getting at whether you could not pursue a biopsy in a patient where you have low probability. It is a reasonable question, but in the clinical context I would be hesitant to say I am basing a decision on a prediction model and therefore I am not going to send the patient for biopsy,” says Dr. Warrington.

GCA is a disease in which “you don’t have a lot of room for error,” he says, because patients suffer devastating consequences if the diagnosis is missed. “We like to have confirmation of the diagnosis because treatment is not trivial and includes several years of glucocorticoids and perhaps other immunosuppressive agents, which all have side effects. A negative biopsy can help exclude a GCA diagnosis, even if the initial suspicion is low,” he says.

As noted above, the proposed model looks only at the probability of finding a positive biopsy, which is different than determining whether a patient has GCA. Many patients diagnosed with GCA actually have negative temporal artery biopsies, says Dr. Grayson.

Dr. Calabrese notes that there is nearly a complete absence of consideration in the model of the large group of GCA patients who have inflammatory presentations. These patients will likely, in the absence of head and neck symptoms, have negative biopsies and are now often diagnosed with vascular imaging.

It’s important to remember, according to Dr. Warrington, that the model authors are ophthalmologists and thus are focusing on patients who present with cranial symptoms such as headache, vision changes and jaw claudication. GCA, however, “comes in a lot of different shapes and sizes,” he says. “Some patients present with only fever of unknown origin; others have involvement of the aorta or subclavian artery and present with arm claudication; some present with stroke; some present with aortic aneurysm.”

Those presentations help a physician decide which diagnostic tool to use. For someone who presents with headache and vision loss, a temporal artery biopsy is probably the best tool. “But if someone has fever of unknown origin and no cranial symptoms, the likelihood of a positive biopsy is low,” Dr. Warrington says. “In that case we rely on imaging to make the diagnosis—CT, MRA or PET—to show inflammation of the large arteries.”

Recent clinical trials have revised inclusion criteria to include patients who were diagnosed by either biopsy or imaging. In some trials, up to half of patients are not diagnosed by biopsy but by imaging, he says.

The prediction model has some utility but should probably be applied only to patients with cranial symptoms and not patients with less common presentations. Incorporating temporal artery ultrasound for GCA diagnosis, as well as imaging large vessels (e.g., the chest arteries) into future models would be wise, Dr. Warrington says.

Regarding the model’s utility for rheumatologists, Dr. Grayson says he thinks the authors indicated its value in their conclusion. The researchers suggested, he says, “that perhaps their prediction model is most useful to help organize thinking but should not be a substitute for clinical decision making.”

Kathy Holliman, MEd, has been a medical writer and editor since 1997.

References

- Ing EB, Luna GL, Toren A, et al. Multivariable prediction model for suspected giant cell arteritis: Development and validation. Clin Ophthalmol. 2017 Nov 22;11:2031–2042.

- Ing EB, et al. The use of a nomogram to visually interpret a logistic regression prediction model for giant cell arteritis. Neuroophthalmology. Accepted for publication January 2018.

- Ing E, Pagnoux C, Tyndel F, et al. Lower ocular pulse amplitude with dynamic contour tonometry is associated with biopsy-proven giant cell arteritis. Can J Ophthalmol. 2017.

- Hunder GG, Bloch DA, Michel BA, et al. The American College of Rheumatology 1990 criteria for the classification of giant cell arteritis. Arthritis Rheum. 1990 Aug;33(8):1122–1128.