HUS and AMD are diseases representative of two distinct types of complement-mediated injury states. The former is an acute injury that leads to microthrombi. This lesion occurs over a few hours and days and is self-limited. The latter is a situation featuring chronic inflammation over years and decades and is ongoing. Neither condition was thought to have a pathologic relationship to innate immunity, specifically to the complement system. However, whole genome screens identified mutations and polymorphisms in complement regulatory genes as predisposing factors. The basic model arising from these studies is that a reduction in the function of a plasma or membrane inhibitor of the AP permits excessive complement activation on renal endothelium in HUS and on retinal debris in AMD. These associations have much to teach us about the host’s innate immune response to acute injury and to chronic debris deposition.

An Example of Acute Injury State

Atypical hemolytic uremic syndrome (aHUS) is one of a group of conditions termed the thrombomicroangiopathies (TMA) that are associated with endothelial cell injury.2–4 Approximately 50% of patients with aHUS (also called familial, sporadic, nonenteropathic, or Shiga toxin– negative HUS) are haploinsufficient for a CIP. Atypical HUS is characterized by the acute onset of the triad of microangiopathic hemolytic anemia, a low platelet count secondary to consumption, and renal failure caused by microthrombi. “Typical” or the epidemic form of HUS most commonly follows an infection featuring bloody diarrhea by a Shiga toxin– producing Escherichia coli.

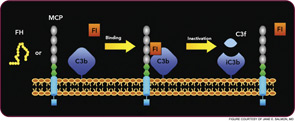

Atypical HUS may not have an identifiable trigger, but serious infections in young children are a common precipitating event. Atypical HUS tends to be lethal (25% of patients die acutely) and recurrent (50% of patients develop permanent kidney failure). The penetrance is about 50%, and the mean age at presentation is younger than five years of age. Atypical HUS is a disease of complement dysregulation, commonly featuring a heterozygous mutation in one of three genes: FH, MCP, or factor I.2–4,18 (See Table 1, at left, and Figure 4, p. 18.) Further, gain-of-function mutations for the activating components factor B and C3 have also now been reported in aHUS.19,20 Identification of a mutation is important in disease management owing to differences in mortality, renal survival, and outcome of kidney transplantation.2–4,18 Current treatment is plasma infusion/exchange, but complement inhibitor therapy provides hope for the future.21–23