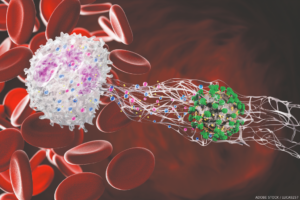

“Dysregulation in neutrophil biology and the formation of neutrophil extracellular traps (NETs) may play a prominent role in the initiation and perpetuation of a number of systemic autoimmune diseases, including systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) and rheumatoid arthritis,” says Mariana J. Kaplan, MD, a distinguished investigator in the systemic autoimmunity branch of the National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases, National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, Md.

“Dysregulation in neutrophil biology and the formation of neutrophil extracellular traps (NETs) may play a prominent role in the initiation and perpetuation of a number of systemic autoimmune diseases, including systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) and rheumatoid arthritis,” says Mariana J. Kaplan, MD, a distinguished investigator in the systemic autoimmunity branch of the National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases, National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, Md.

Dr. Kaplan is the author of a review that is part of a series on immunology for rheumatologists launched earlier this year in Arthritis & Rheumatology (A&R).1 In this new installment, Dr. Kaplan explores the role of NETs in SLE.2

The comprehensive review builds on a case study demonstrating the clinical manifestations of SLE while exploring the role of NETs in the pathogenesis, diagnosis and treatment of SLE. Dr. Kaplan refers to the case study throughout the review, which includes many references, along with a detailed figure demonstrating the mechanisms by which NETs promote autoimmunity and organ damage in SLE.

Dr. Kaplan

“Current evidence supports a role for neutrophil subsets and NETs in organ complications and in the development of premature cardiovascular disease,” says Dr. Kaplan.

Case Study

The case study follows a 31-year-old woman patient presenting with a six-month history of fatigue, joint pain, intermittent fevers and a rash exacerbated by the sun. She first noticed the symptoms following an upper respiratory tract infection six months earlier. The patient also reported non-painful, recurrent mouth ulcers, Raynaud’s phenomenon and hair loss for the past three months. Her symptoms persisted despite taking acetaminophen and avoiding sun exposure.

A physical examination showed a red, macular malar rash, sparing the nasolabial folds, a maculopapular rash on her upper arms, oral ulcers, and swelling and tenderness in her knees and multiple joints in her hands and feet.

Laboratory tests indicated leukopenia; lymphopenia; mild neutropenia; an elevated erythrocyte sedimentation rate; normal C-reactive protein levels; increased levels of anti-nuclear antibodies, anti-double-stranded DNA and anti-Ro antibodies; and decreased C3 and C4 levels.

Renal function test results were normal, with no proteinuria. Other findings included low high-density lipoprotein; elevated low-density lipoprotein and total cholesterol; bilateral increased carotid intimal media thickness; an impaired cholesterol efflux capacity; elevated myeloperoxidase (MPO):DNA remnants and citrullinated histone H3:DNA remnants consistent with NETs and the presence of low-density granulocytes (LDGs).

“Given the clinical presentation and laboratory findings, you diagnose the patient with SLE and pre-clinical atherosclerosis and dyslipidemia, and initiate an antimalarial, a statin and low-dose prednisone, as well as advising her regarding sun protection, vitamin D intake, warranted vaccinations and other general preventive measures for SLE comorbidities,” Dr. Kaplan writes.