Prostock-studio / shutterstock.com

ACR CONVERGENCE 2021—Rheumatic conditions can affect the eye in myriad ways, but ocular inflammation can be challenging for the rheumatologist to understand and manage. Jason Kolfenbach, MD, associate professor of medicine and ophthalmology, and program director of the Rheumatology Fellowship Program, University of Colorado School of Medicine, Aurora, and Alan G. Palestine, MD, professor of ophthalmology and medicine, and chief of the Uveitis and Ocular Immunology Section, University of Colorado School of Medicine, provided a unique overview of inflammatory eye disease and the overlap with systemic rheumatic illnesses at an ACR Convergence 2021 session.

Rheumatology & the Eye

Dr. Kolfenbach discussed the intersection between rheumatology and ophthalmology with an intriguing case-based presentation. “The eye is a common target of many rheumatic illnesses,” he said. “Most inflammatory eye disease is idiopathic, but studies estimate 25 to 40% of uveitis and more than 50% of nodular or necrotizing scleritis are associated with an underlying systemic illness.”1,2

First, Dr. Kolfenbach shared the case of a young woman with Cogan syndrome, which is characterized by acute-onset ocular and audiovestibular signs within one to six months of each other. Interstitial keratitis, bilateral sensorineural hearing loss and vestibular dysfunction are classic presentations, although other manifestations may occur. These patients may also experience constitutional symptoms, joint pain, lymphadenopathy and a medium- to large-vessel vasculitis, which occurs in 15–20% of cases. Treatment depends on the manifestation present, with ocular disease responding well to topical steroids, hearing loss to oral immunosuppressants like methotrexate or azathioprine, and vasculitis typically requiring cyclophosphamide.3

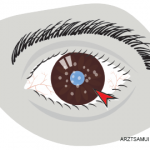

Next, he turned to the case of a 69-year-old gentleman with untreated ankylosing spondylitis and unilateral anterior uveitis. His exam was notable for ciliary flush in the limbus region of the eye and synechiae. “White blood cells and protein in the anterior chamber cause stickiness between the iris and lens, resulting in synechiae—which is essentially an adhesion between these two structures in the eye,” Dr. Kolfenbach explained. He offered the following pearl: “If unilateral uveitis is recurrent, spondyloarthritis (SpA) comprises nearly half of cases, so we need to identify and intervene earlier to ensure better SpA outcomes over time.”

Uveitis may often feel like the tip of the iceberg, with a laundry list of infectious malignant and inflammatory conditions as potential etiologies. So where does one start? Dr. Kolfenbach recommended approaching the differential based on the anatomic segment of the eye involved. For recurrent uveitis cases, he recommends:

- A thorough history and exam, with a focus on extraocular signs and symptoms.

- A chest radiograph given the prevalence of sarcoidosis, and the ability to identify other common culprits, such as granulomatosis with polyangiitis (GPA) and tuberculosis.

- Syphilis testing, because it’s easy to treat.

Of note, an isolated unilateral episode of uveitis may not require an extensive evaluation. “Obtaining a chest radiograph and syphilis testing is quick and easy, but additional evaluation and referral to a rheumatologist may not be necessary [because] the uveitis episode may be the first and last occurrence,” Dr. Kolfenbach clarified.

He also touched on anterior scleritis, and the far rarer and vision-threatening posterior scleritis, which comprises only 2% of cases but is harder to diagnose.4 He offered the following pieces of wisdom: “Nodular scleritis confers a high risk of connective tissue disease and conversion to necrotizing disease. Seropositive rheumatoid arthritis rarely presents with scleritis, but GPA may.”

Dr. Kolfenbach reminded us that “in patients with autoimmune disease, not every ‘exacerbation’ is from the underlying rheumatic illness.” Vigilance for ocular infection must remain high, especially in the immunosuppressed patient, [because] misdiagnosis can have vision-threatening consequences.

A Common Language

For the second half of the presentation, Dr. Palestine stressed the importance of finding a common language to describe ocular inflammation; this is imperative to defining therapeutic success and failure. Rheumatologists and ophthalmologists don’t describe eye issues in the same way. What’s more, ophthalmologists may also use variable descriptions because ocular immunology specialists are few and far between.

“Redness is subjective,” he reminded us. “Classification criteria were just recently developed for uveitis, but 50% of cases still don’t fit within these criteria. We have a long way to go regarding a uniform understanding of these diseases.”5

Vigilance for ocular infection must remain high, especially in the immunosuppressed patient because misdiagnosis can have vision-threatening consequences.

The Ophthalmologist’s Point of View

Dr. Palestine offered valuable insight from the perspective of the co-managing ophthalmologist. “A search for a systemic disease association is always worthwhile given the therapeutic implications, but don’t be disappointed. We often find nothing,” he said. He recommended defining the location, course and progression of eye disease, and then framing the evaluation around history, clinical findings and imaging. “I recommend a targeted workup to avoid costly false positives. Atypical clinical findings or treatment response would justify more extensive testing.”

Regarding testing specifics, Dr. Palestine noted, “Syphilis and sarcoid screening have a high positive predictive value in uveitis. Anti-neutrophil cytoplasmic antibody testing is reasonable in retinal vasculitis. Viral serologies, quantiferon testing, anti-nuclear antibody, rheumatoid factor and inflammatory markers, on the other hand, are rarely useful.”

Regarding immunosuppression, Dr. Palestine encouraged rheumatologists to take the reins. “Rheumatologists have the expertise in prescribing and managing these drugs, and ocular immunologists are uncommon. Few randomized, controlled trials (RCT) exist to guide therapeutic choices, so work closely with the ophthalmologist to determine the best drug regimen, duration and goal of therapy. Then, communicate the plan to the patient as a unified front,” he said.

Dr. Palestine typically treats inflammatory eye disease for two to three years at minimum, but no RCT data exist to support this approach. “Stopping therapy depends on the consequences of recurrence. Some recurrences do not lead to permanent vision loss. Others do, so the risk of discontinuation is higher,” he added.

In Sum

Drs. Kolfenbach and Palestine celebrated the benefits of collaboration across their fields, and hope other institutions will follow suit in developing rheumatology-ophthalmology clinics. When we work together, it’s easy to see how the rheumatologist, ophthalmologist and patient all win, they noted.

Samantha C. Shapiro, MD, is an academic rheumatologist and an affiliate faculty member of the Dell Medical School, University of Texas at Austin. She received her training in internal medicine and rheumatology at Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore. She is also a member of the ACR Insurance Subcommittee.

References

- Akpek EK, Thorne JE, Qazi FA, et al. Evaluation of patients with scleritis for systemic disease. Ophthalmology. 2004 Mar;111(3):501–506.

- Jakob E, Reuland MS, Mackensen F, et al. Uveitis subtypes in a German interdisciplinary uveitis center—Analysis of 1916 patients. J Rheumatol. 2009 Jan;36(1):127–136.

- Mazlumzadeh M, Matteson EL. Cogan’s syndrome: An audiovestibular, ocular, and systemic autoimmune disease. Rheum Dis Clin North Am. 2007 Nov;33(4):855–874.

- Nevares A, Raut R, Libman B, Hajj-Ali R. Noninfectious autoimmune scleritis: Recognition, systemic associations, and therapy. Curr Rheumatol Rep. 2020 Mar 26;22(4):11.

- Standardization of Uveitis Nomenclature (SUN) Working Group. Development of classification criteria for the uveitides. Am J Ophthalmol. 2021 Aug;228:96–105.