Learning to become a physician is a process that requires personal experience from which we edit our observations and hone our skills. Each of us is profoundly influenced by personal experience, but I chide medical trainees that we should not always learn from our own results. Perhaps that claim is why one resident evaluated me: “He says some bizarre things, and sometimes I think he isn’t kidding.” Let’s say, however, that you prescribe a biologic for RA, and the patient dies from an infection. Wouldn’t that have a huge impact on the likelihood that you will prescribe the same biologic in the future, even if the odds of this serious adverse event are small? Personal experience is more persuasive than the best designed randomized, controlled trial.

If you are a practicing physician, you have prescribed medication that produced an adverse effect. This does not require an error in judgment. It is an inevitable component of experience. Obviously we strive to avoid error; we cannot avoid risk.

Paul

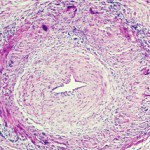

I evaluate Paul, a spry, kindly, 80-year-old academician who has suddenly lost vision in one eye. He has suffered an ischemic optic neuropathy which could be due to a treatable disease, giant cell arteritis, or more likely is due to a more difficult condition to treat, atherosclerotic disease in small vessels. I ask about symptoms such as jaw claudication or proximal muscle stiffness that would suggest the arteritis. I check the sedimentation rate, which is normal. I elect to biopsy the temporal artery and find no evidence of vasculitis. But none of these approaches has 100% sensitivity, meaning that it is possible to have giant cell arteritis with no symptoms except visual loss. Possible but not very likely.

The treatment of giant cell arteritis, corticosteroids, almost always has some toxicity, and so logically and appropriately I recommend no prednisone therapy. But there remains a chance, a tiny chance, that Paul does have giant cell arteritis. Both atherosclerosis and giant cell arteritis place him at risk for bilateral visual loss. If Paul goes blind in his remaining eye, I may not know the cause, but I do know how I will feel. The first response of virtually every physician to an unhappy outcome is: What did I do wrong?

The IOM concluded that our errors kill more frequently than breast cancer or AIDS or motor vehicle accidents. The IOM has done a great service by calling attention to medical errors because some errors can be systematically avoided. Many “errors,” however, are not errors at all; they reflect probabilities and logical judgments.