I am not a risk taker.

I do not bungee jump.

I have never gone helicopter skiing.

I have not tried parasailing.

I always wear my seat belt.

I cross the street at the crosswalk—mostly.

And every day I make judgments that expose patients to the risk of death.

Phyllis

Phyllis, a no-nonsense professional, retired after a 40-year career in New York City and moved to Oregon to be near her children. She had severe, deforming rheumatoid arthritis (RA) and was being treated with a stable regimen of medications that included methotrexate. When I assumed her care, I adhered to a personal rule, which had served me well over two decades of practice: Never change the therapeutic combination on the first meeting if the patient perceives that it is working.

Phyllis was not taking folic acid when we first met and, consequently, I never added it to her medication mix. Although folic acid mitigates the side effects of methotrexate, it can also diminish its efficacy. Phyllis never reported any difficulty tolerating methotrexate. Over the many years that I cared for her, we tried various biologics and other approaches for her disease. I monitored her laboratory tests diligently. Phyllis’ arthritis relentlessly progressed.

The call I received from a resident one morning produced that sinking abdominal feeling that most physicians know all too well. Phyllis had been hospitalized for aplastic anemia. The likely cause was methotrexate. Folic acid does not always prevent aplastic anemia related to methotrexate use and prescribing it with methotrexate is not a universal practice, but the studies are persuasive that it substantially reduces the likelihood of this rare toxicity. Phyllis did not recover.

Julia

Julia was a stoic, determined, active septuagenarian who rarely allowed her deforming arthritis to interfere with her vitality. Her son called me routinely one afternoon: “I can’t bring mama to her appointment tomorrow; she has the flu, no energy, and no appetite. She’s taking aspirin. I’ll let you know when she’s better.” Perhaps a few more questions might have prevented the call that came two days later. “I went to bring mama breakfast, and I found her dead in her bed.” My patient had died of a gastrointestinal hemorrhage.

The Institute of Medicine (IOM) has issued reports on how many patients have succumbed from medical errors. The IOM defines an error as “the failure of a planned action to be completed as intended … or the use of a wrong plan to achieve an aim.” An error is not the same as an adverse event, but an error is nearly the same as a preventable adverse drug event, which is one “arising because of an error.” These seemingly simple words require Talmudic interpretation. What, for example, is preventable, or how does one define a wrong plan?

In considering Julia’s death as an example, it is well known that aspirin increases the risk of gastrointestinal bleeding. But let’s say for the sake of argument that the increase is a whopping 90%. To use rounded figures, if the risk of a bleed in any given year is one in 100, a 90% increase would mean the risk goes up to 1.9 per 100. This means, in turn, that one is still more likely to have a bleed spontaneously even without taking aspirin. Whether the medication increased the risk 10% or 1,000%, that risk was balanced by some perceived gain.

I can only guess when Julia’s bleeding began. Was this indeed the flu, with the bleed coming later? Or, all along, was this simply an ulcer with symptoms of fatigue and aching that mimicked flu? What was the contribution of factors such as other medications, smoking, alcohol use, or stress? And what was my obligation to ask about tarry bowel movements? I am not sure why, on this particular fall day, I happened to field a call about cancelling an appointment, a call that would normally prompt just a routine message from my secretary. Even to this day, I would not be likely to enquire of a patient who complains of flu-like symptoms, “So tell me, what color are your stools?”

“Do you think that I could have saved her?” her tearful son asked me.

“Do you think that I could have saved her?” my conscience asked me.

Exploring Probabilities

Medical advice rests on probabilities: Take this antibiotic because there is a 90% chance that the bug infecting you is sensitive to it. But probabilities always have a flip side. If there is a 90% chance that the antibiotic will help, there is a 10% chance that it will not be beneficial. And there is a separate, additional dimension—the probability of harm. The probability might be less than 1% with antibiotics, but, in circumstances like the use of chemotherapy for certain malignancies, the likelihood of some harm might approach 100%. As physicians, we sometimes forget that our advice relies on probability.

The implication of these considerations is that the best, most rationale advice may not produce the intended outcome. Probabilities mean that a bad outcome is not always tantamount to bad judgment. In offering medical advice, we, as rheumatologists, arguably wrestle with more uncertainty than any other subspecialty. However, even a cardiologist should hospitalize a few patients for chest pain that is not cardiac in origin. Even the best general surgeon should take out an occasional appendix that bears no abnormality.

Learning to become a physician is a process that requires personal experience from which we edit our observations and hone our skills. Each of us is profoundly influenced by personal experience, but I chide medical trainees that we should not always learn from our own results. Perhaps that claim is why one resident evaluated me: “He says some bizarre things, and sometimes I think he isn’t kidding.” Let’s say, however, that you prescribe a biologic for RA, and the patient dies from an infection. Wouldn’t that have a huge impact on the likelihood that you will prescribe the same biologic in the future, even if the odds of this serious adverse event are small? Personal experience is more persuasive than the best designed randomized, controlled trial.

If you are a practicing physician, you have prescribed medication that produced an adverse effect. This does not require an error in judgment. It is an inevitable component of experience. Obviously we strive to avoid error; we cannot avoid risk.

Paul

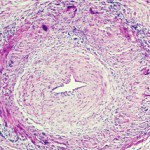

I evaluate Paul, a spry, kindly, 80-year-old academician who has suddenly lost vision in one eye. He has suffered an ischemic optic neuropathy which could be due to a treatable disease, giant cell arteritis, or more likely is due to a more difficult condition to treat, atherosclerotic disease in small vessels. I ask about symptoms such as jaw claudication or proximal muscle stiffness that would suggest the arteritis. I check the sedimentation rate, which is normal. I elect to biopsy the temporal artery and find no evidence of vasculitis. But none of these approaches has 100% sensitivity, meaning that it is possible to have giant cell arteritis with no symptoms except visual loss. Possible but not very likely.

The treatment of giant cell arteritis, corticosteroids, almost always has some toxicity, and so logically and appropriately I recommend no prednisone therapy. But there remains a chance, a tiny chance, that Paul does have giant cell arteritis. Both atherosclerosis and giant cell arteritis place him at risk for bilateral visual loss. If Paul goes blind in his remaining eye, I may not know the cause, but I do know how I will feel. The first response of virtually every physician to an unhappy outcome is: What did I do wrong?

The IOM concluded that our errors kill more frequently than breast cancer or AIDS or motor vehicle accidents. The IOM has done a great service by calling attention to medical errors because some errors can be systematically avoided. Many “errors,” however, are not errors at all; they reflect probabilities and logical judgments.

Several years after Phyllis’ death, I crossed paths with her son at a memorial for a mutual friend. My ability to recognize faces is woeful and, when a familiar face appears in a new context, I am usually at a loss. The son was gracious enough to remind me of our relationship. “You know, my mother was always so grateful for everything you did for her,” he said.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the Stan and Madelle Rosenfeld Family Trust, the William and Mary Bauman Foundation, and the William C. Kuzell Foundation (formerly the Fund for Arthritis and Infectious Disease Research).

The author is grateful to Lisa Rosenbaum, Sandra Lewis, Alex de Saint Sardos, Pascale Schwab, and Alan Seif, who made constructive comments about the manuscript.

Dr. Rosenbaum is head of the division of arthritis and rheumatic diseases at the Oregon Health & Science University, where he also holds the Edward E Rosenbaum Chair in Inflammation Research. His essays have appeared in Science and JAMA.