A 14-year-old boy from Cape Verde was referred to rheumatology clinic for evaluation of arthritis, fevers, and weight loss. Three weeks earlier, he began to notice left ankle pain and swelling. Over the next few days, his right ankle, both knees, and left elbow also became swollen and painful. He complained of bilateral hip and neck pain. He noticed that he had morning stiffness that improved somewhat with movement, although he felt stiff throughout the day.

In addition, he developed fevers as high as 102.5º F, which occurred almost daily and most commonly at night. He described nondrenching night sweats and a decreased appetite with an 18-pound weight loss. He was evaluated by a physician in Cape Verde who prescribed naproxen, which was not helpful. Due to the persistence of his symptoms, the patient was brought to Boston for further medical management.

He was admitted to another hospital for further workup of his fever and polyarthritis. Laboratory workup revealed thrombocytosis and elevated inflammatory markers. Urinalysis demonstrated pyuria. All studies for infectious causes of his illness were negative. Other lab results are shown in Table 1. A chest X-ray was normal. Imaging of the hips and sacroiliac joints was normal. He was referred to the rheumatology clinic for further evaluation.

Our First Encounter

At age 10, the patient had developed a similar episode of painful arthritis, weight loss, and fevers up to 104º F. He was hospitalized for three weeks in Cape Verde, and was transferred to Portugal for further management. At that time, he was diagnosed with rheumatoid arthritis (RA), and treated with naproxen. Within six months, his symptoms completely resolved and he remained free of symptoms until his current presentation.

His past medical history included asthma. He was not taking any medications and had no allergies. His family was of Cape Verdian origin. A maternal cousin was diagnosed with arthritis during adolescence and was receiving monthly injections for his condition. There was no family history of lupus, thyroid disease, inflammatory bowel disease, psoriasis, or other autoimmune conditions. He was attending the 10th grade. He denied any alcohol or drug use and was not sexually active.

On physical examination, he was a tall, thin male using a wheelchair to enter the exam room. His blood pressure was 100/55 mm Hg, pulse 107 beats per minute, and he was afebrile. His weight was 113 pounds (32nd percentile), height 69 inches (78th percentile), and BMI 16.7 (7th percentile). His musculoskeletal exam was remarkable for left elbow arthritis, with full extension lacking by 10 degrees. His right elbow range of motion was normal. He had tenderness and swelling along the flexor tendon of the third digit of his right hand. There was slight sacroiliac joint tenderness bilaterally. The hip showed mildly decreased range of motion. The right knee had a small effusion and was tender at the insertion of the patellar tendon. His left knee was normal, and both knees had full range of motion. His ankles were warm, markedly swollen, and tender without overlying erythema. The Achilles tendons were swollen and tender bilaterally (see Figure 1). Both feet were swollen and tender, and he had dactylitis of the great toes. Gait could not be assessed because of pain. The nails were normal without pits, and there were no rashes. The rest of his exam was unremarkable.

Laboratory Results

Laboratory tests confirmed raised markers for inflammation and thrombocytosis. Testing for human leukocyte antigen (HLA) B27, sent from the other hospital, returned positive. Further laboratory workup revealed negative occult fecal blood, and his stool culture was negative for Campylobacter, Enterohemorrhagic E. coli, Salmonella, Shigella, and Yersinia.

The diagnosis of a reactive arthritis (ReA) was made and the patient was prescribed prednisone 60 mg daily. His fevers quickly resolved, and over the next few weeks his arthritis improved. Although he had some swelling of the ankles and the dorsum of the feet, he was able to resume playing soccer. Repeat bloodwork four weeks later showed a normalization of blood counts and inflammatory markers. One month later, sulfasalazine 1,000 mg twice daily was prescribed and prednisone was weaned and discontinued. The arthritis completely resolved within a few months, and he continues to do well without disease recurrence.

Discussion

Take-Home Points

- The differential diagnosis of fever and arthritis is fairly limited in children and adults.

- ReA usually occurs one to four weeks after gastrointestinal or genitourinary infection.

- ReA presents with painful arthritis predominantly affecting lower extremites, and can cause enthesitis, dactylitis, and systemic symptoms.

- ReA is most often caused by Chlamydial infections in adults, while gastrointestinal infections are the most common cause of ReA in children.

- ReA and the spondylarthropathies appear to fall within the spectrum of the polygenic autoinflammatory diseases.

- Treatment may include NSAIDs, DMARDs, systemic corticosteroids, and biologics for recalcitrant disease.

- Prognosis is good, although the presence of HLA-B27 may raise the risk for severe disease and a more chronic course.

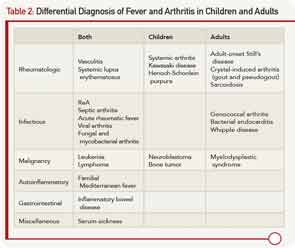

The presence of arthritis and fever has a fairly limited differential diagnosis in children and adults, and a comprehensive, expedited evaluation should take place to avoid the potential morbidity and mortality of some important diseases. The differential diagnosis is listed in Table 2. The age of onset, pattern of fever, type and number of joints involved, associated symptoms, laboratory testing, and synovial fluid analysis may lead to the diagnosis.

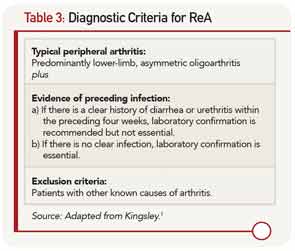

Traditionally, ReA is diagnosed by using the Berlin Third International Workshop on Reactive Arthritis criteria (1995) shown in Table 3.1 Criteria include an asymmetric oligoarthritis, predominantly involving the lower limbs, and clinical or laboratory evidence of a preceding infection with enteric or genitourinary organisms including Chlamydia trachomatis, Shigella, Salmonella, Yersinia, and Campylobacter. Nevertheless, recent reports have also implicated atypical organisms as causative agents of ReA, including Giardia lambia and Clostridium difficile, as well as intravesical Bacillus Calmette-Guerin therapy for bladder cancer.2,3

In children, gastrointestinal infections are the most common cause of ReA. In adults, C. trachomatis is the most common inciting organism.7 Prospective studies of adults with Chamydial infections have shown that 4% to 8% of adults infected will develop ReA.8 Because Chamydial infections are often asymptomatic, the resultant arthritis may not be properly diagnosed as ReA.4 Thus, the true incidence of ReA is largely unknown.

ReA is not considered to be a septic arthritis because cultures from synovial fluid are sterile. Nevertheless, modern polymerase chain reaction (PCR) techniques have demonstrated the presence of bacterial antigens from triggering organisms in the synovium of affected joints.

ReA occurs one to four weeks after the inciting infection.4 It usually presents as an acute, painful, sometimes erythematous oligoarthritis (four or fewer joints involved). Arthritis most commonly affects the lower extremities, typically the knees and ankles. In a recent study, enthesitis was the most common musculoskeletal finding in patients with ReA.5 Dactylitis, or sausage digits, may also be present. Back pain and stiffness can develop due to axial involvement. Extraarticular features include fever, painless oral ulcers, urethritis, sterile pyuria, erythema nodosum, and keratoderma blennorhagicum (psoriasiform lesions on the palms and soles that are pathognomonic for ReA).4 During the acute phase of the illness, there are elevated inflammatory markers, thrombocytosis, anemia, leukocytosis, and hypergammaglobulinemia, as were seen in this patient. Autoantibodies including rheumatoid factor, cyclic citrillunated protein, and antinuclear antibodies, are negative.

Pathogenesis

As a type of spondylarthritis, ReA shares many clinical characteristics with the other spondylarthropathies, including a strong association to HLA-B27. However, unlike ankylosing spondylitis, where HLA-B27 is present in about 90% of patients, the prevalence of HLA-B27 in ReA is estimated to be between 30% and 50%.4

The pathogenesis of the spondylarthropathies is not well understood. In patients who are HLA-B27 positive, there is evidence of misfolding of the HLA-B27 protein inside the endoplasmic reticulum. This results in heightened cellular stress that leads to activation of NF-kB and release of proinflammatory cytokines, creating an inflammatory response in the joint.6 This evidence supports the idea that the spondylarthropathies are within the spectrum of polygenic autoinflammatory diseases, in which local factors activate the innate immune system to cause tissue-specific inflammation. This is in contrast to autoimmune diseases such as lupus, in which disease-specific autoantibodies, self-reactive lymphocytes, and enhanced activation of the adaptive immune system are key to the pathogenesis of the disease.

Can bacteria in the gut or genitourinary tract trigger joint inflammation? One theory suggests that Chlamydial antigens share homology with peptides bound to HLA-B27, thus causing activation of the immune system as a result of molecular mimicry.13 However, bacterial stress in general, perhaps through pathogen-associated molecular patterns, may be sufficient to cause activation of an abnormal innate immune response that leads to an inflammatory arthritis. Similarly, mechanical stress and trauma at and around the joints may also trigger damage-associated molecular patterns and activation of the innate immune system, creating an inflammatory arthritis. The importance of physical stress to the pathogenesis of spondylarthritis is exemplified by the preference of inflammation in locations of repeated trauma such as the entheses, spine, and the lower extremity joints.6

The incidence of ReA around the world is probably related to the prevalence of arithrogenic bacteria and HLA-B27 positive patients in specific populations. The capability of bacteria to trigger ReA may vary among different strains of the same species. Epidemics of ReA have followed outbreaks of bacterial infections including Yersinia and Campylobacter in Finland, Shigella in Afghanistan, and Salmonella in Spain.9-12

The prognosis of ReA is usually good. For most patients, the episode of arthritis resolves within three to six months.18 The majority of patients do not develop a chronic inflammatory arthritis.19 A minority of patients will have a relapsing course, especially in the setting of repeated infections with the same organism, as likely happened to our patient. The risk of developing a more severe and chronic disease appears to be increased in those patients who are HLA-B27 positive.20

Send us Your Case Suggestion

Have you managed a patient with an unusual rheumatologic problem that you would want to present to a larger audience? Consider submitting your case to The Rheumatologist.

We are looking for interesting cases that are well written and that provide useful teaching points to the reader. Send an outline of your case presentation to Simon Helfgott, MD, at shelf [email protected], or visit www.The-Rheumatologist.org for more information.

The initial treatment of ReA usually includes nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), which can provide symptom relief but do not affect the course of disease. If the disease is severe, or there are significant systemic symptoms, some patients may benefit from oral corticosteroids. If ReA becomes chronic, disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs (DMARDs) such as sulfasalazine, methotrexate, or leflunomide can be added to the regimen. Small studies of adult patients have shown that tumor necrosis factor inhibitors appear to be safe and effective in patients with refractory disease.14 A recent case report also showed the efficacy of tocilizumab, an interleukin-6 receptor antagonist, in treating ReA.15

The use of long-term antibiotics to treat ReA remains controversial. A randomized trial suggests that a six-month course of antibiotic therapy may be effective for Chamydial ReA, but this has not been observed for other causative organisms.16 A recent meta-analysis of antibiotic treatment for ReA failed to show any benefit, although the included trials were very heterogeneous.17 Prevention of ReA may be possible by the prompt recognition and treatment of Chamydial infections, but this has not been shown for other causes of ReA.21

The recognition of the autoinflammatory nature of this disease and the role of the innate immune system in its pathogenesis may help guide future treatment.

Dr. Hausmann is a pediatric and adult rheumatology fellow at Boston Children’s Hospital and Beth Israel Medical Center.

References

- Kingsley G, Sieper J. Third International Workshop on Reactive Arthritis. 23–26 September 1995, Berlin, Germany. Report and abstracts. Ann Rheum Dis. 1996;55:564-584.

- Morris D, Inman RD. Reactive arthritis: Developments and challenges in diagnosis and treatment. Curr Rheumatol Rep. 2012;14:390-394.

- Bernini L, Manzini CU, Giuggioli D, Sebastiani M, Ferri C. Reactive arthritis induced by intravesical BCG therapy for bladder cancer: Our clinical experience and systematic review of the literature. Autoimmun Rev. 2013;12:1150-1159.

- Carter JD, Hudson AP. Reactive arthritis: Clinical aspects and medical management. Rheum Dis Clin North Am. 2009;35:21-44.

- Townes JM. Reactive arthritis after enteric infections in the United States: The problem of definition. Clin Infect Dis. 2010;50:247-254.

- Ambarus C, Yeremenko N, Tak PP, Baeten D. Pathogenesis of spondyloarthritis: Autoimmune or autoinflammatory? Curr Opin Rheumatol, 2012;24:351-358.

- Rich E, Hook EW, Alarcón GS, Moreland LW. Reactive arthritis in patients attending an urban sexually transmitted diseases clinic. Arthritis Rheum. 1996;39:1172-1177.

- Carter JD, Inman RD. Chlamydia-induced reactive arthritis: Hidden in plain sight? Best Pract Res Clin Rheumatol. 2011;25:359-374.

- Vasala M, Hallanvuo S, Ruuska P, Suokas R, Siitonen A, Hakala M. High frequency of reactive arthritis in adults after Yersinia pseudotuberculosis O:1 outbreak caused by contaminated grated carrots. Ann Rheum Dis. 2013; Jul 12. [Epub ahead of print]

- Martin DJ, White BK, Rossman MG. Reactive arthritis after Shigella gastroenteritis in American military in Afghanistan. J Clin Rheumatol. 2012;18:257-258.

- Arnedo-Pena A, Beltrán-Fabregat J, Vila-Pastor B, et al. Reactive arthritis and other musculoskeletal sequelae following an outbreak of Salmonella hadar in Castellon, Spain. J Rheumatol. 2010;37:1735-1742.

- Hannu T, Kauppi M, Tuomala M, Laaksonen I, Klemets P, Kuusi M. Reactive arthritis following an outbreak of Campylobacter jejuni infection. J Rheumatol. 2004;31:528-530.

- Alvarez-Navarro C, Cragnolini JJ, Santos Dos HG, et al. Novel HLA-B27-restricted epitopes from Chlamydia trachomatis generated upon endogenous processing of bacterial proteins suggest a role of molecular mimicry in reactive arthritis. J Biol Chem. 2013; 288:25810-25825.

- Meyer A, Chatelus E, Wendling D, et al. Safety and efficacy of anti-tumor necrosis factor α therapy in ten patients with recent-onset refractory reactive arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 2011;63:1274-1280.

- Tanaka T, Kuwahara Y, Shima Y, et al. Successful treatment of reactive arthritis with a humanized anti-interleukin-6 receptor antibody, tocilizumab. Arthritis Rheum. 2009;61:1762-1764.

- Carter JD, Espinoza LR, Inman RD, et al. Combination antibiotics as a treatment for chronic Chlamydia-induced reactive arthritis: A double-blind, placebo-controlled, prospective trial. Arthritis Rheum. 2010;62:1298-1307.

- Barber CE, Kim J, Inman RD, Esdaile JM, James MT. Antibiotics for treatment of reactive arthritis: A systematic review and metaanalysis. J Rheumatol. 2013;40:916-928.

- Kvien TK, Gaston JSH, Bardin T, et al. Three month treatment of reactive arthritis with azithromycin: A EULAR double blind, placebo controlled study. Ann Rheum Dis. 2004;63:1113-1119.

- Laasila K, Laasonen L, Leirisalo-Repo M. Antibiotic treatment and long-term prognosis of reactive arthritis. Ann Rheum Dis. 2003;62:655-658.

- Leirisalo-Repo M, Helenius P, Hannu T, et al. Long term prognosis of reactive salmonella arthritis. Ann Rheum Dis. 1997;56:516-520.

- Bardin T, Enel C, Cornelis F, et al. Antibiotic treatment of venereal disease and Reiter’s syndrome in a Greenland population. Arthritis Rheum. 1992;35:190-194.