Take Home Points

- Antisynthetase syndrome may present without muscle involvement.

- Careful attention should be paid to the skin examination.

- Antisynthetase antibody testing, particularly anti-Jo-1, should be performed in all patients with ILD without an obvious etiology because pulmonary involvement may be the sole presenting manifestation.

- Coexistent SSA positivity is a marker of more severe lung disease.

The Case

A 24-year-old white male was seen in July 2012 because of multiple complaints. He had been doing well until three weeks earlier, when he developed pain and diminished hearing in his left ear, which was accompanied by cough and a postnasal drip. He had had two tympanostomies due to left ear problems in the past, and attributed the current symptoms to the same problem.

One week later, he developed pain and swelling in multiple joints. The joint pain was of sudden onset and involved his shoulders, wrists, fingers, and feet. He could not make a fist due to the pain and swelling.

One week later, he complained of shortness of breath and described two episodes of hemoptysis—a tablespoon full of bright red blood each time—that brought him to a community hospital. He felt warm but denied any chills, night sweats, or weight loss. He recalled removing a dead flat tick from his back a few days earlier. He was treated with doxycycline and a five-day course of prednisone for a presumed tick-borne illness. The prednisone improved his joint pain and swelling. He was an otherwise healthy male. He occasionally took antihistamine pills for treatment of nasal allergy symptoms.

His father had severe rheumatoid arthritis (RA) and his mother was recently diagnosed with sarcoidosis. He was married without children and denied smoking, alcohol, or illicit drug use. He denied any extramarital sexual activity. He worked as a taxidermist and was exposed to oxalic acid, tannic acid, and some other oils. He had no pets. Travel history was unremarkable.

After the five-day course of prednisone 20 mg, he continued to cough but denied hemoptysis. Joint swelling and pain recurred. At the community hospital, a chest radiograph showed interstitial and alveolar infiltrates and bilateral pleural effusions. He underwent a bronchoscopy and a bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL), which was negative for any infection. Results for acid-fast bacilli and serologies for common tick-borne diseases were negative. Intravenous vancomycin and ceftriaxone were administered for possible pneumonia. He continued to have joint pains and was referred to our facility on his third hospital day.

Upon arrival, he denied any prior episodes of pulmonary or joint symptoms. He did report noticing some dryness of his hands with minimal scaling at the onset of these symptoms. He did not have any other rashes, eye problems, chronic sinus issues, oral/nasal/genital sores, Raynaud’s phenomenon, photosensitivity, sicca symptoms, dysphagia, aspiration, abdominal pain, neuropathic symptoms, or bladder symptoms.

On examination he was afebrile with a temperature of 98.9º F, a pulse of 85/min, blood pressure of 124/83 mmHg, respiratory rate of 18.

There was no sinus tenderness. Fine inspiratory crackles at both bases were heard on pulmonary examination. Cardiac exam was unremarkable. He had a faint scaly rash on the palmar aspect of some of his fingers. There were no nail-fold capillary changes. He had noticeable tenderness and swelling in the metacarpophalangeal, proximal interphalangeal, and metatarsophalangeal joints. His back, sacroiliac, and entheseal exams were normal. His neurological examination was normal. No muscle weakness or tenderness was present.

The hemoglobin was 10.5 (13.5–17.5 g/dL), with normal white blood cell and platelet count. Routine serum chemistries and liver function tests were normal. His Westergren erythrocyte sedimentation rate was 46 (0–15 mm/hr) and his C-reactive protein was 21 (0–10 mg/L). Urinalysis, creatinine kinase, hepatitis panel, HIV screen, and serum ferritin were unremarkable.

A new chest radiograph showed consolidation in the left lung base, nodular opacities in both lungs, and small bilateral pleural effusions (see Figure 1). A computed tomography (CT) scan of the chest showed multifocal areas of ground-glass and reticular opacities, predominantly in the bilateral lower lobes, along with bronchiectasis (see Figure 2). No cavitary or nodular lesions were identified. Pulmonary function testing (PFT) revealed a restrictive pattern with a forced vital capacity at 53% of expected value and carbon monoxide diffusion capacity at 50% of predicted value. A six-minute walk test resulted in oxygen desaturation to 80% on room air. A transthoracic echocardiogram was normal.

Results of rheumatological workup included a rheumatoid factor (RF) of 119 (0–14 IU/mL), homogenous antinuclear antibody (ANA) pattern with a titer of >1:640, SSA and SSB of 8 (0–0.9 AI), SSB and ribonucleoprotein antibody of 1.4 (0–0.9 AI). Antineutrophil cytoplasmic (ANCA) antibody, Smith, DNA, antiglomerular basement membrane, scl-70, and cyclic citrullinated antibodies were all negative. Serum angiotensin converting enzyme, complement, and cryoglobulins levels were normal.

A CT scan of the sinuses showed soft-tissue opacification of the right maxillary sinus without bony destruction along with multiple subcentimetric lymph nodes.

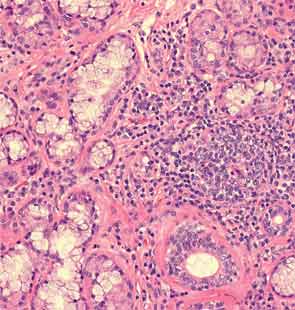

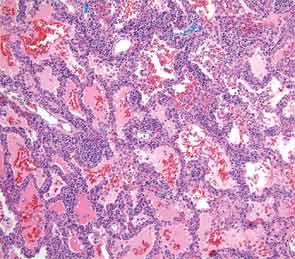

An extensive infectious disease workup for viral infections, tuberculosis, fungi, and bacteria was negative. A transbronchial biopsy was negative for any infectious etiology or granulomas. Histopathology revealed nonspecific interstitial pneumonitis (NSIP) pattern. The otolaryngology service was consulted for a minor salivary gland biopsy, which was subsequently reported as being consistent with Sjögren’s syndrome (SS) based on more than one focus of more than 50 lymphocytes per 4 mm2 (see Figure 3). A surgical lung biopsy confirmed NSIP (see Figure 4); fibrosis was absent. At this time, the anti-Jo-1 antibody was reported as positive at 7.9 (0–0.9 AI)). The serum aldolase level was elevated at 9.4 (1.5–8.1 U/L).

A diagnosis of antisynthetase syndrome with subclinical SS—based on positive serologies and biopsy in the absence of sicca symptoms—was made. The patient was placed on oral prednisone at 1 mg/kg and hydroxychloroquine 200 milligrams twice daily. After three days of treatment, he had a remarkable response and his joint symptoms resolved. At three months of follow-up, he was on prednisone 40 mg, had no complaints, and his PFT and chest radiograph had normalized. He was started on methotrexate 10 mg weekly to allow for steroid taper.

Discussion

Rheumatologists are often asked to evaluate patients presenting with interstitial lung disease (ILD) in association with a positive ANA or RF, joint, or musculoskeletal symptoms. This case highlights one such typical scenario. The initial concern was for an ANCA-associated disease based on the presence of aural symptoms, hemoptysis, lung disease, and arthritis. However lack of ANCA antibody positivity, absence of any bony erosion on sinus imaging, and subsequent biopsy without histological evidence of vasculitis merited a diagnostic reevaluation.

Antisynthetase syndrome is a systemic autoimmune syndrome characterized by a variable combination of ILD, myopathy, fever, joint involvement, and mechanic’s hands with a reported prevalence of 1.5 per 100,000. Its hallmark is the presence of antibodies directed against aminoacyl-transfer RNA synthetase of which the most frequent is the anti-Jo-1 antibody that accounts for about 80% of all cases of antisynthetase syndrome.1 Other relatively common antibodies include anti-PL-7 and anti-EJ.2 Anti-Jo-1 antibodies are present in about 30% of patients presenting with myositis and it is in the setting of myositis that these antibodies are usually tested to diagnose antisynthetase syndrome. ILD, however, is the most frequently occurring manifestation of antisynthetase syndrome and is reported in 75% to 89% of all cases.3 Lung involvement is the most important determinant of prognosis.

ILD is the most frequent manifestation, and in some cases the sole one, of antisynthetase syndrome.3 In about 20% of cases, the plain radiographs are read as normal, despite pulmonary involvement. When this diagnosis is being considered, high resolution CT scanning of the chest should be performed. Common findings include bilateral basal consolidations, diffuse patchy ground-glass opacities and subpleural prominence. On lung biopsy, NSIP is the most common pattern seen, although it is not specific for antisynthetase syndrome. Biopsy is important to rule out infections, granulomatous diseases, and vasculitis. It can also determine whether there is lung fibrosis. The absence of fibrosis predicts a better response to therapy. Although hemoptysis is not a regular feature of pulmonary involvement in antisynthetase syndrome, it has been reported.

Joint symptoms are more common in anti-Jo-1 positive patients and can mimic common inflammatory arthritides.4 RF, for example, can be positive in 10% to 20% of subjects with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (IPF). Patient with IPF can also have arthralgias, and it is important to look for secondary clues to an underlying connective tissue disease (CTD) before labeling any disease as idiopathic.

The lack of a unifying diagnosis, positive family history for a CTD, and absence of any identifiable environmental exposure or infection in the setting of a strongly positive SSA/SSB prompted the minor salivary gland biopsy, despite the fact that the patient did not have typical symptoms or the CT findings expected in SS. As noted, the biopsy was consistent with SS.

The utility of obtaining salivary gland biopsies in such settings can be debated, owing to false-positive rates and the significant variability in their interpretation. However, one study evaluating ILD patients without an underlying cause found 34% of patients having a biopsy suggestive of SS, of which 23% were negative for ANA, SSA, and SSB.5 About 23% of those with a positive biopsy denied sicca symptoms. The authors postulated that SS was subclinical in these patients. They also felt identification of a patient with an underlying disease, in this case SS—whether clinical or subclinical—conferred a better prognosis than the diagnosis of idiopathic ILD. It is difficult to say whether a salivary gland biopsy should be considered in an otherwise asymptomatic patient with an idiopathic ILD. SSA is frequently seen in association with anti-Jo-1, and evidence suggests an increased severity of ILD in patients with SSA positive antisynthetase syndrome.6

The lack of muscle symptoms in this patient contributed to the delay in arriving at the final diagnosis. It is important to note that myositis may not be one of the presenting features in antisynthetase syndrome. In one series of ILD patients with anti-Jo-1 antibodies, myositis was present in only 31% at initial presentation.3 The anti-Jo-1 presence can precede clinical myositis by years.

In cases where no obvious etiology is identifiable, a careful skin and nail-fold capillary exam is warranted. In this case, the faint scaly rash on the hands at the onset of disease was a subtle clue that prompted testing for the anti-Jo-1 antibodies. Such a rash could be easily dismissed as eczema or occupation related both by the patient and the physician. The classic rash of antisynthetase syndrome is fissured, scaly, and erythematous, located on the palmar and lateral surfaces of fingers and hand.

The patient was exposed to aerosol agents related to his occupation, though no link of the specific compounds with ILD could be made. One series of patients with antisynthetase syndrome reported 39% of subjects having occupational aerosol exposures.3 The potential role of these exposures in initiating inflammation merits further study.

It has been suggested that antisynthetase syndrome antibodies should be tested in all patients presenting with ILD, as the presentation can be nonspecific in the early stages. This is especially true in cases with an acute presentation, NSIP pattern or lymphocytic alveolitis on histopathology, or lymphocyte predominance on BAL.3,7 Determining the antibody status may serve as a predictor of late-onset myopathy and also furnish prognostic information because anti-Jo-1 positive patients respond better to treatment, although recurrences are more common.8,9 Anti-Jo-1 seropositivity, however, does not seem to influence survival.7,8

Most treatment regimens for this condition depend on a combination of glucocorticosteroids and other immunosuppressants. Glucocorticosteroids are generally considered first-line treatment, typically at an initial dose of prednisone equivalent of 1 mg/kg, with pulmonary disease response dictating treatment duration. Other agents that have been used include mycophenolate mofetil, cyclophosphamide, cyclosporine, azathioprine, intravenous immunoglobulin, tacrolimus, and rituximab.

Dr. Aslam is a rheumatology fellow at the University of Arkansas for Medical Sciences in Little Rock, Ark. Dr. Russell is associate professor and program director at the University of Arkansas for Medical Sciences.

References

- Dalakas MC, Hohlfeld R. Polymyositis and dermatomyositis. Lancet. 2003;362:971-982.

- Kalluri M, Sahn SA, Oddis CV, et al. Clinical profile of anti-PL-12 autoantibody. Cohort study and review of the literature. Chest. 2009;135:1550-1556.

- Tillie-Leblond I, Wislez M, Valeyre D, et al. Interstitial lung disease and anti-Jo-1 antibodies: Difference between acute and gradual onset. Thorax. 2008;63:53-59.

- Mielnik P, Wiesik-Szewczyk E, Olesinska M, Chwalinska-Sadowska H, Zabek J. Clinical features and prognosis of patients with idiopathic inflammatory myopathies and anti-Jo-1 antibodies. Autoimmunity. 2006;39:243-247.

- Fischer A, Swigris JJ, du Bois RM, et al. Minor salivary gland biopsy to detect primary Sjogren syndrome in patients with interstitial lung disease. Chest. 2009;136:1072-1078.

- La Corte R, Lo Mo Naco A, Locaputo A, Dolzani F, Trotta F. In patients with antisynthetase syndrome the occurrence of anti-Ro/SSA antibodies causes a more severe interstitial lung disease. Autoimmunity. 2006;39:249-253.

- Watanabe K, Handa T, Tanizawa K, et al. Detection of antisynthetase syndrome in patients with idiopathic interstitial pneumonias. Respir Med. 2011;105:1238-1247.

- Yoshifuji H, Fujii T, Kobayashi S, et al. Anti-aminoacyl-tRNA synthetase antibodies in clinical course prediction of interstitial lung disease complicated with idiopathic inflammatory myopathies. Autoimmunity. 2006;39:233-241.

- Katzap E, Barilla-LaBarca ML, Marder G. Antisynthetase syndrome. Curr Rheumatol Rep. 2011;13:175-181.