HLH is a syndrome of excessive immune activation of mononuclear phagocytes with elevated cytokines, which can result in a difficult to control hyperinflammatory response.1 It can present as a febrile illness associated with multiple organ involvement. Some common presentations include fever of unknown origin, hepatitis, encephalitis or a mimic of common infections. HLH can be diagnosed by the molecular identification of an HLH-associated gene mutation or the presence of five out of eight criteria, as listed in Table 1.2-4 Macrophage activation syndrome (MAS) is HLH that usually occurs in association with a rheumatologic condition, such as AOSD.

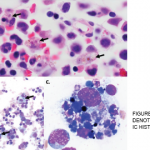

Based on the HLH-2004 trial, there are two types of HLH: 1) primary (or familial) HLH, which occurs due to a genetic mutation and 2) secondary (or acquired) HLH, which is usually associated with an infection, malignancy or autoimmune disorder. HLH is usually triggered by a variety of events that disrupt the homeostasis of the immune system. The pathognomonic finding in HLH is the presence of hemophagocytosis, which can be found in the bone marrow, lymph nodes, spleen or liver.1 HLH can be life-threatening and catastrophic with an overall mortality of 58–75%.1 Hence, it is important to establish the diagnosis as quickly as possible and initiate immediate treatment. This is often challenging given the rareness of this syndrome, the variable spectrum of clinical presentation, and the lack of specific clinical and laboratory findings to diagnose this condition.

Our patient was initially thought to have AOSD. The Yamaguchi criteria (see Table 1) are used to aid in the diagnosis of AOSD and require the presence of five features, with at least two being major diagnostic criteria.4 Our case met five criteria, but did not have findings of the classic evanescent, salmon-colored rash or leukocytosis. Typically, patients with AOSD have leukocytosis, unless the disease has progressed to MAS/HLH, at which point they are noted to be cytopenic.

HLH & Malignancy

HLH has been associated with lymphoid cancers, including T, NK and anaplastic large-cell lymphomas, as well as leukemias, which include B cell lymphoblastic leukemia and solid tumors.5 The diagnosis of HLH may precede the finding of the malignancy, but this is rare.6 Lymphoma-associated hemophagocytic syndrome (LAHS) is a type of HLH that accounts for approximately 40% of adult-onset secondary HLH and has a poor prognosis.7

A retrospective chart review study evaluated the clinical and laboratory findings, as well as the prognostic factors, of adult HLH in a cohort of 74 patients from 2003 to 2014; 73 patients, with a median age of 51 years, met the HLH-2004 diagnostic criteria. Fever, cytopenias and elevated ferritin were noted in greater than 85% of cases. Infection was the associated etiology of HLH in 41%; whereas, 28.8% of cases were due to malignancy. To a lesser extent, there was an association of HLH with autoimmune conditions (7%), post-solid organ transplantation (3%) and primary immunodeficiency (1.4%); the remaining cases were labeled idiopathic (18%). This study demonstrated that cases with malignancy-associated HLH had a significantly worse survival compared with patients with non-malignancy-associated HLH (median overall survival 1.1 vs. 46.5 months, respectively; P<0.0001). Analysis of these patients’ 30-day mortality rates showed that a ferritin greater than 50,000 µg/L was the only poor predictor.1