Necrotizing autoimmune myopathy (NAM) is a relatively recently discovered subgroup of inflammatory myopathies. NAM is characterized by predominant muscle fiber necrosis and regeneration with little or no inflammation.1 One subgroup of NAM is 3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl-CoA reductase antibody (HMGCR Ab)-related immune-mediated necrotizing myopathy (IMNM), which occurs (rarely) after statin exposure, with a rough incidence of two per 1 million per year.2,3,4,5,6

Approximately one in 10,000 people exposed to statins develop myalgia and myopathy, which reverse after doctors discontinue statins.7 These patients are usually in their fifth decade of life and present with subacute to chronic symmetric muscular weakness with high creatine phosphokinase (CPK) levels (9,718 ± 7,383 IU/L) and poor response to steroids.2 The presentation can occasionally be complicated by severe respiratory weakness, dysphagia and ventricular dysfunction.3

Below, we discuss two patients with HMGCR Ab-related IMNM with severe respiratory muscle weakness. Our case series highlights the uncommon presentation of respiratory muscle involvement leading to respiratory failure, and identifies the best treatment.

Case Report 1

The first patient was a 76-year-old Caucasian male who presented with progressive subacute proximal weakness in his upper and lower extremities, and difficulty in swallowing. His muscle weakness started 10 weeks prior to admission and gradually worsened. One week prior to his admission, he noticed difficulty swallowing and nasal regurgitation.

Figure 1. This H&E stain of Patient 1’s muscle biopsy shows normal muscle with minimal necrosis.

His system reviews were negative for shortness of breath, diplopia, skin rash, B type symptoms, cough and similar episodes in the past. His past medical history was significant for hypertension and hypercholesterolemia, for which he was on lisinopril and atorvastatin. The patient did mention a recent increase in his atorvastatin dosage. His physical exam revealed profound proximal muscle weakness in his upper and lower extremities. The rest of the exam proved unremarkable.

His initial laboratory work-up revealed mild microcytic hypochromic anemia, normal creatinine (1.0 mg/dL), elevated aspartate aminotransferase (AST) (300 IU/L) and significantly elevated CPK levels (8,214 U/L). Based on his presentation and initial laboratory work-up, we were concerned about statin-induced myopathy, so we discontinued atorvastatin. We also started him on steroids, because he had profound muscle weakness with dysphagia and markedly elevated CPK.

Additional laboratory work revealed negative antinuclear antibody (ANA) and an extended myositis panel positive for HMGCR Ab of >200 U (normal is 0–19 U). The patient underwent electromyography (EMG), which showed myopathic process. A muscle biopsy showed normal with minimal necrosis. His initial computerized tomography (CT) of chest and negative inspiratory force (NIF) were normal (>-25). His modified barium swallow revealed moderate cricopharyngeal weakness with a high risk of aspiration, so we placed a nasogastric tube for nutrition. The patient showed no evidence of occult malignancy on imaging.

The patient reported initial improvement in his weakness, but his CPK remained elevated (although lower than his admission levels). On day six of his hospitalization, he reported worsening weakness with dyspnea on exertion and at rest. He underwent an NIF and CT angiogram (CTA) of his chest for evaluation of new onset respiratory distress. His NIF was low (-5), and his repeat chest CTA highlighted atelectasis without any consolidations or effusions or embolism. We intubated him for poor inspiratory effort, and gave him pulse-dose steroids for three days. We added intravenous immunoglobulin (IVIG) because the patient had severe respiratory muscle involvement leading to respiratory failure, along with profound muscle weakness despite the initial steroid therapy.

On day eight of his hospitalization, he developed severe pneumococcal sepsis with distributive shock, requiring four vasopressors. His family decided to withdraw care after discussion with the intensive care team and pulmonologist.

Unlike other statin-associated myopathies, HMGCR Ab-related IMNM features a complex pathogenesis characterized by extensive myocyte necrosis with scarce phlogistic infiltration in biopsy & the presence of HMGCR antibodies.

Case Report 2

Figure 2A: This H&E stain of Patient 2’s muscle biopsy shows necrotic muscle fibers with mild inflammatory cell infiltration.

The second patient was a 47-year-old African-American male with a progressive subacute proximal weakness of his upper and lower extremities. His symptoms started eight weeks prior to admission and gradually worsened. The patient also reported having difficulty swallowing, nasal regurgitation, dyspnea on exertion and voice changes. These symptoms also started eight weeks prior to hospitalization.

His review of systems was negative for diplopia, skin rash, B type symptoms, cough and joint pain. His past medical history was significant for hypertension, stroke with right-side residual weakness, and hypercholesterolemia. At home, the patient was taking rosuvastatin, lisinopril and aspirin without any recent change in the doses.

On physical examination, we noticed tachypnea, shallow breathing, profound proximal muscle weakness, a weak cough and a low-pitched, husky voice. The rest of his physical examination proved unremarkable.

His initial laboratory work-up revealed mild normocytic normochromic anemia (hemoglobin 11.2 g/dL), normal creatinine (1.0 mg/dL), elevated AST levels (323 IU/L) and significantly elevated CPK levels (10,214 U/L). We grew concerned about statin-induced myopathy, so we discontinued rosuvastatin. His ancillary test revealed negative ANA and a positive extended myositis panel with HMGCR Ab >200 U. His EMG was consistent with irritable myopathy. The patient underwent a muscle biopsy from his right deltoid muscle, which revealed atrophic and necrotic muscle fibers, and mild inflammatory infiltrate.

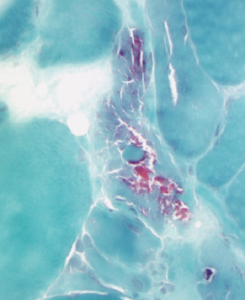

Figure 2B: This acid phosphatase stain of Patient 2’s muscle biopsy shows large numbers of necrotic fibers (highlighted in the center of the image).

Because our patient was in respiratory distress, we evaluated him for cardiac dysfunction and respiratory involvement. Transthoracic echocardiography showed 40% ejection fraction with mild to moderate left ventricular systolic and diastolic dysfunction. His chest CT demonstrated no evidence of interstitial lung disease (ILD), and his NIF measured <-15, highlighting significant respiratory muscle involvement. His arterial blood gas revealed hypoxic hypercapnic respiratory failure, and we intubated him after he failed a bilevel positive airway pressure (BiPAP) trial.

We started the patient on a combination of high-dose steroids and IVIG, because he had severe muscle weakness with profound respiratory muscle involvement leading to respiratory failure. During hospitalization, his weakness improved and his CPK levels trended down to 800 U/L. We continued him on steroids and monthly IVIG. On his follow-up visit two months later, his respiratory status and muscle strength had significantly improved.

Triggered by Statins?

Unlike other statin-associated myopathies, HMGCR Ab-related IMNM features a complex pathogenesis characterized by extensive myocyte necrosis with scarce phlogistic infiltration in biopsy and the presence of HMGCR antibodies.8,9 The recently discovered HMGCR Ab is composed of 200 kDa and 100 kDa proteins with specificity for the carboxy terminus of the HMGCR enzyme.10 Based on immunoprecipitation assays, these antibodies may be a causal link between statin exposure and IMNM.10 A study by Mammen et al reports the prevalence of these HMGCR antibodies in all patients suspected of inflammatory myopathy to be around 6%, making it the second most common myositis-specific antibody after the anti-Jo1 antibody.11

The proposed pathogenesis of statins is through upregulation of the expression of MHC1 and the HMGCR enzyme in regenerating muscle fibers.2,7,12 Overexpression of MHC1 may result from endoplasmic reticulum stress induced by HMGCR inhibition, leading to depletion of metabolic intermediates.12,13 Endoplasmic reticulum stress leads to activation of the NF-kB pathway, which in turn activates the cytokine and chemokine production involved in immune processes.

Muscle Attack

After the initial trigger of the autoimmune process, researchers hypothesize muscle damage is sustained by overexpression of HMGCR in regenerating muscle even after statins are discontinued.11,14 This supposition is supported by the discovery of upregulated HMCGR expression in cells expressing neural cell adhesion molecules (NCAM) in regenerating muscle fibers.11 This explains the progressive weakness found in these patients even after statin discontinuation.

The complete pathogenesis of HMGCR Ab-related IMNM remains blurry, but other findings (such as the presence of few infiltrating lymphocytes and membrane attack complex on non-necrotic muscle cell membranes) support the pathogenic nature of HMGCR autoantibodies.10 Also, evidence from other studies that HMGCR autoantibody levels correlate with initial elevated CPK levels and muscle weakness supports the pathogenicity of these antibodies.15,16

Although HMGCR is usually not expressed on the surface of myocytes, researchers hypothesize that under different pathological conditions it can be expressed on the surfaces of different cells.17,18 This highlights a clear association between statin exposure and an antibody triggered autoimmune reaction leading to IMNM.

However, we must note that more than 33% of the patients in various study groups were statin-naive.10,11,19 The statin-naive patients with HMGCR Ab-related IMNM are relatively young and have severe disease presentation with poor response to steroids and other immunomodulatory therapy.

HMGCR Ab-related IMNM’s common presentation includes subacute to chronic, moderate to severe proximal muscle weakness, with CPK elevation higher than the levels commonly seen in other inflammatory myopathies.11 Different studies have revealed different ranges of CPK levels. For example, a study by Grable-Esposito et al reports mean CPK levels of 8,203 IU/L, but a study by Christopher-Stine et al notes higher mean CPK levels of 10,333 IU/L.

A recent NAM review showed that extra-muscular manifestations, such as ILD and cardiac involvement, occur less frequently in HMGCR Ab-related IMNM compared with other NAM subgroups.3,20 Allenbach et al report in their study that around 20% of patients with HMGCR Ab-related IMNM presented with dysphagia and respiratory muscle involvement without evidence of ILD.19 The literature doesn’t include many cases that feature HMGCR Ab-related IMNM presenting with severe respiratory muscle involvement leading to respiratory failure requiring mechanical ventilation.

Immunosuppression Required

HMGCR Ab-related IMNM initially shows mild to moderate response to steroids, but most patients develop progressive muscle weakness, and their high CPK levels remain, which indicates the need to step up therapy. Studies have highlighted the role of various immunomodulatory therapies, such as methotrexate, cyclophosphamide, rituximab, IVIG and azathioprine, in ameliorating symptoms in these patients.3 Further, in patients with severe disease presentation, researchers propose a role of aggressive immunomodulation with combination immunosuppressive therapy.3,19

In our case series, the first patient diagnosed with HMGCR Ab-related IMNM had moderate initial response to steroids, but he later developed rapid progression of muscle weakness with significant respiratory muscle involvement. Therefore, we added IVIG, but unfortunately, he died due to pneumococcal sepsis.

The second patient initially presented with severe respiratory muscle weakness leading to hypoxic hypercapnic respiratory failure and cardiac involvement. Therefore, we gave him a combination of IVIG and high-dose steroids, and he responded well.

Conclusion

HMGCR Ab-related IMNM can present with severe respiratory muscle weakness that leads to hypoxic hypercapnic respiratory failure, dysphagia and cardiac involvement, which can contribute to significant morbidity and mortality. Persistently high CPK levels, progressive muscle weakness, dysphagia and respiratory muscle involvement include some of the indicators of severe disease. Doctors must promptly identify such patients and manage them with aggressive immunosuppression.

Shivani Garg, MD, is an assistant professor in the Department of Internal Medicine, Division of Rheumatology at the School of Medicine and Public Health in the University of Wisconsin in Madison, Wis.

Shivani Garg, MD, is an assistant professor in the Department of Internal Medicine, Division of Rheumatology at the School of Medicine and Public Health in the University of Wisconsin in Madison, Wis.

Suzana Alex John, MD, is a fellow in the Department of Rheumatology at Emory University in Atlanta.

Suzana Alex John, MD, is a fellow in the Department of Rheumatology at Emory University in Atlanta.

Frehiywot Ayele, MD, is an assistant professor in the Department of Rheumatology at Emory University in Atlanta.

Frehiywot Ayele, MD, is an assistant professor in the Department of Rheumatology at Emory University in Atlanta.

References

- Carroll MB, Newkirk MR, Sumner NS. Necrotizing autoimmune myopathy: A unique subset of idiopathic inflammatory myopathy. J Clin Rheumatol. 2016 Oct;22(7):376–380.

- Mohassel P, Mammen AL. Statin-associated autoimmune myopathy and anti-HMGCR autoantibodies. Muscle Nerve. 2013 Oct;48(4):477–483.

- Basharat P, Christopher-Stine L. Immune-mediated necrotizing myopathy: Update on diagnosis and management. Curr Rheumatol Rep. 2015 Dec;17(12):72.

- Albayda J, Christopher-Stine L. Identifying statin-associated autoimmune necrotizing myopathy. Cleve Clin J Med. 2014 Dec;81(12):736–741.

- Hoogendijk JE1, Amato AA, Lecky BR, et al. 119th ENMC international workshop: Trial design in adult idiopathic inflammatory myopathies, with the exception of inclusion body myositis. Neuromuscul Disord. 2004 May;14(5):337–345.

- Ramanathan S, Langguth D, Hadry T, et al. Clinical course and treatment of anti-HMGCR antibody-associated necrotizing autoimmune myopathy. Neurol Neuroimmunol Neuroinflamm. 2015 Apr 2;2(3):e96.

- Mammen AL. Statin-associated autoimmune myopathy. N Engl J Med. 2016 Feb 18;374(7):664–669.

- Meriggioli MN. The clinical spectrum of necrotizing autoimmune myopathy: A mixed bag with blurred lines. JAMA Neurol. 2015 Sep;72(9), 977–979.

- Giudizi MG, Cammelli D, Vivarelli E, et al. Anti-HMGCR antibody-associated necrotizing myopathy: Diagnosis and treatment illustrated using a case report. Scand J Rheumatol. 2016 Oct;45(5):427–429.

- Christopher-Stine L, Casciola-Rosen LA, Hong G, et al. A novel autoantibody recognizing 200-kd and 100-kd proteins is associated with an immune-mediated necrotizing myopathy. Arthritis Rheum. 2010 Sep;62(9):2757–2766.

- Mammen AL, Chung T, Christopher-Stine L, et al. Autoantibodies against 3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl-coenzyme A reductase in patients with statin-associated autoimmune myopathy. Arthritis Rheum. 2011 Mar;63(3):713–721.

- Musset L, Allenbach Y, Benveniste O, et al. Anti-HMGCR antibodies as a biomarker for immune-mediated necrotizing myopathies: A history of statins and experience from a large international multi-center study. Autoimmun Rev. 2016 Oct;15(10):983–993.

- Lahaye C, Beaufrére AM, Boyer O, et al. Immune-mediated myopathy related to anti 3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl-coenzyme A reductase antibodies as an emerging cause of necrotizing myopathy induced by statins. Joint Bone Spine. 2014 Jan;81(1):79–82.

- Mammen AL. Autoimmune myopathies: Autoantibodies, phenotypes and pathogenesis. Nat Rev Neurol. 2011 Jun 8;7(6):343–354.

- Werner JL, Christopher-Stine L, Ghazarian SR, et al. Antibody levels correlate with creatine kinase levels and strength in anti-3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl-coenzyme A reductase-associated autoimmune myopathy. Arthritis Rheum. 2012 Dec;64(12):4087–4093.

- Mammen L, Pak K, Williams EK, et al. Rarity of anti-3-hydroxy-3-methylglutarly-coenzyme A reductase antibodies are rare in statin users, including those with self-limited musculoskeletal side-effects. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken). 2012 Feb;64(2):269–272.

- Levenson VV. Biomarkers for early detection of breast cancer: What, when and where? Biochim Biophys Acta. 2007 Jun;1770(6):847–856.

- Misek DE, Kim EH. Protein biomarkers for the early detection of breast cancer. Int J Proteomics. 2011;2011.

- Allenbach Y, Drouot L, Rigolet A, et al. Anti-HMGCR autoantibodies in European patients with autoimmune necrotizing myopathies: Inconstant exposure to statin. Medicine (Baltimore). 2014 May;93(3):150–157.

- Kassardjian CD, Lennon VA, Alfugham NB, et al. Clinical features and treatment outcomes of necrotizing autoimmune myopathy. JAMA Neurol. 2015 Sep;72(9):996–1003.