Sarcoidosis is a multisystem disease of unknown origin characterized by noncaseating granulomas in involved organs. This disease primarily affects the lungs in more than 90% of cases, but extrathoracic manifestations such as cutaneous, lymphatic system, ocular, and liver involvement are commonly present.1 Patients may be asymptomatic at presentation or may have nonspecific symptoms such as fever, malaise, cough, and dyspnea on exertion.1

The diagnosis of sarcoidosis is established when the clinical and radiologic findings are supported by histological evidence of noncaseating epithelioid cell granulomas, once all the other causes of granulomatous conditions have been ruled out.2

Although the complete pathophysiology of sarcoidosis is not well understood, it is known that tumor necrosis factor (TNF)–α plays a major role in sarcoidosis development, and TNF-α inhibitors have been used for the treatment of refractory sarcoidosis.3,4 In contrast, a few case reports have described a paradoxical effect, with TNF-α inhibitor therapy leading to the development of granulomatous disease or sarcoidosis.

Here we describe new cases of sarcoidosis in two psoriatic arthritis patients treated with TNF-α inhibitor therapy. The first patient was treated with etanercept and the second with adalimumab.

Case #1

A 47-year-old white man with longstanding psoriasis involving mainly his scalp, abdomen, and back and arthritis involving mainly his metacarpophalangeal and proximal interphalangeal joints, wrists, and knees was followed in our rheumatology clinic. He was treated with methotrexate but continued to experience intermittent flares of the rash and arthritis for which he required multiple doses of prednisone or intraarticular corticosteroid injections. Methotrexate was subsequently discontinued due to a persistently elevated serum alkaline phosphatase. Etanercept 50 mg subcutaneously weekly was started in April 2005 and there was marked improvement and remission of both psoriasis and joint disease.

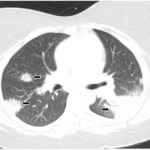

Four years later, the patient developed dyspnea on exertion and a nonproductive cough. Etanercept was discontinued. A chest X-ray (CXR) demonstarted a large right-sided mediastinal mass. Computed tomography (CT) of the chest revealed large subcarinal lymphadenopathy measuring 5.8 x 3 x 2.4 cm and peritracheal lymphadenopathy measuring 2.4 x 2.7 cm (see Figure 1).

A bronchoscopy and fine needle aspiration (FNA) of a mediastinal lymph node yielded tissue showing granulomatous inflammation. Cytology studies were negative for lymphoma. Acid fast bacilli (AFB) and fungal cultures were negative. Purified protein derivative (PPD) skin test was reported as nonreactive. Pulmonary function tests (PFTs) showed decreased vital capacity to 77% of predicted and decreased diffusion lung carbon monoxide capacity (DLCO) to 57% of predicted. Sarcoidosis was felt to be the most likely diagnosis. Etanercept was restarted and the patient was also treated with prednisone. Repeat chest CT imaging one month later showed decreased lymphadenopathy. Upon resolution of respiratory symptoms, prednisone was discontinued.

Although the patient remained asymptomatic, approximately one year later, a new chest CT study showed enlargement of existing mediastinal and hilar lymph nodes and new additional mediastinal nodes. Etanercept was discontinued due to a suspicion that it may be related to the relapse of sarcoidosis, and sulfasalazine was started in conjunction with a prednisone taper. Two months after discontinuation of etanercept, another chest CT showed decrease in size of the subcarinal lymph node and the right paratracheal nodes. PFTs showed a stable vital capacity of 77%, DLCO 59%, and forced expiratory volume (FEV1) was normal at 86% of predicted.

While on sulfasalazine, the patient was able to cope with his skin and joint disease. Intermittent joint flares were treated with intraarticular corticosteroid injections while psoriasis flares were treated with topical corticosteroids.

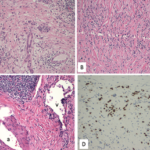

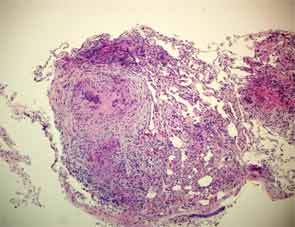

Two years later, the patient developed dyspnea on exertion and a nonproductive cough. PFTs showed a decrease in the vital capacity to 71% and DLCO to 55% of predicted. FEV1 decreased to 77% of predicted. This time, chest CT imaging showed improvement in mediastinal and hilar adenopathy, but there was an increase in parenchymal manifestations of sarcoid disease with perilymphatic distribution of nodules in upper lobes of lungs bilaterally. A bronchoscopy with biopsy was performed and excised tissue was consistent with noncaseating granulomas (see Figure 2). Repeat AFB and fungal cultures were negative. Serum calcium was 9.1(8.3–10.5 mg/dl) and angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) 49 (9–67 U/L). Because of his poorly controlled sarcoidosis, the patient was started on infliximab 300 mg intravenously every eight weeks. Four months later, the patient was free of respiratory, skin, and joint symptoms. He continues to do well and denies any dyspnea on exertion or other systemic manifestations of sarcoid disease while on infliximab. The pulmonary function tests are stable. The chest radiograph appearance has improved and his exercise tolerance improved.

Case #2

A 32-year-old white male with a history of psoriasis diagnosed in 1998 presented to rheumatology clinic in 2007 with a two-week history of pain and swelling in his hands, ankles, shoulders, and low back. Physical exam revealed erythematous plaques covered by silvery white scaly lesions over his lower extremities and there was onycholysis in several fingernails. There was an asymmetric synovitis involving his wrists, metacarpophalangeal and proximal interphalangeal joints, and both ankles. He was diagnosed with psoriatic arthritis and started on prednisone and methotrexate. A baseline CXR was unremarkable. After one month of treatment with methotrexate, the dose was reduced because of elevated serum transaminases, and the prednisone dose was increased due to persistent arthritis. This regimen offered only moderate disease control and it resulted in significant weight gain. Adalimumab 40 mg subcutaneously every other week was initiated.

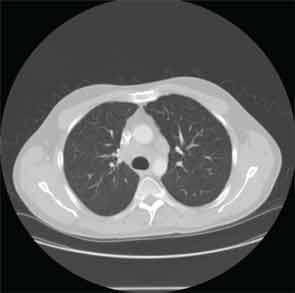

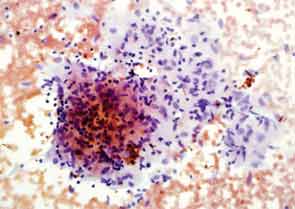

Eighteen months later, the patient developed cough and dyspnea on exertion and was diagnosed with pneumonia at another facility. He was treated with antibiotics and adalimumab was discontinued. His shortness of breath persisted, and a CT of the chest noted lymphadenopathy and bilateral pleural effusions. He was subsequently referred to thoracic medicine clinic at our institution. PFTs revealed significantly decreased mid flow and forced expiratory flow (FEF 25–75%), suggestive of small airway limitation. Serum calcium was 9.0 (8.3–10.5 mg/dl) and ACE level 38 (9–67 U/L). Bronchoscopy with lymph node FNA was performed, with histological findings showing a mixed population of lymphocytes with granulomatous inflammation, negative for malignant cells (see Figure 3). Flow cytometry revealed a reactive population of B and T lymphocytes. The diagnosis was thought to be sarcoidosis and, because this disease began while on a TNF inhibitor, no further drugs of that class were initiated.

The patient remained on varying doses of prednisone and naproxen due to lack of follow-up and noncompliance. He gained significant weight while on prednisone. Eventually, after his compliance improved, methotrexate was restarted and his joint pain improved, but his skin lesions persisted despite additional treatment with topical corticosteroids. There has been no change in the appearance of his hilar adenopathy and there are no new parenchymal lung lesions.

Although the complete pathophysiology of sarcoidosis is not well understood, it is known that TNF-α plays a major role in sarcoidosis development, and TNF-α inhibitors have been used for the treatment of refractory sarcoidosis. In contrast, a few case reports have described a paradoxical effect, with TNF-α inhibitor therapy leading to the development of granulomatous disease or sarcoidosis.

Discussion

In this report, we described two new cases of pulmonary sarcoidosis that occurred during treatment with TNF-α inhibitor therapy in patients with psoriatic arthritis.

Granuloma formation is central in the pathogenesis of sarcoidosis, possibly as a result of an exaggerated immune response to an unknown environmental antigen.3 Granuloma formation starts with activation of T helper 1 (Th1) cells and macrophages that accumulate at the site of inflammation and release cytokines, chemoattractants, and growth factors such as TNF-α, interleukin (IL) 12, interferon γ (INF-γ), IL-18, and transforming growth factor β, among others.1,2 TNF-α is overexpressed in sarcoidosis and is critical to the pathogenesis of granulomas. Proposed mechanisms include proapoptotic activities and pathogenic role in clearing the implicated antigen, both of which can lead to granuloma formation and subsequent fibrogenesis.3

TNF-α inhibitors have been thought to suppress granuloma formation and have been tried in the treatment of refractory sarcoidosis, with varying results.4 Therefore, the development of sarcoidosis in our patients treated with TNF-α inhibitors is an unexpected occurrence. To our knowledge, this is the first case of sarcoidosis development in a psoriatic arthritis patient treated with adalimumab.

There are differences among the different classes of TNF-α inhibitors and the way they can be related to the development of sarcoidosis.5,6 For example, the TNF-α monoclonal antibodies, infliximab and adalimumab, can cause cytotoxic complement-induced lysis of cells expressing membrane-linked TNF-α and cell apoptosis in T cells. In contrast, the soluble TNF-α receptor, etanercept, does not fix complement and does not induce apoptosis.2,4 This may explain etanercept’s more frequent association with the formation of granulomas.2 When TNF-α inhibitors were used in the treatment of sarcoidosis, infliximab was associated with significant improvement, whereas etanercept was associated with worsening disease in patients with progressive pulmonary sarcoidosis.4,7

There has also been a suggestion of an infectious etiology, mainly mycobacterial infection, being associated with the development of sarcoidosis.1 Mycobacterial infections have been reported as an adverse event of treatment with TNF-α inhibitors. It is possible that TNF-α inhibitors may allow or reactivate a mycobacterial infection, which could be linked to sarcoidosis pathophysiology.

In summary, we report two cases of sarcoidosis in patients with psoriatic arthritis following the use of TNF-α inhibitors—one with etanercept, a soluble receptor, and one with adalimumab, a monoclonal antibody. As physicians, we need to be aware of the possibility of sarcoidosis development while treating patients who have psoriatic arthritis with TNF-α inhibitors.

Dr. Cote is a fellow in the department of rheumatology, Dr. Harrington is assistant director of rheumatology, Dr. Meadows is a fellow in the department of internal medicine, Dr. Lin is director of anatomic pathology, and Dr. Bili is a rheumatologist and investigator; all are at Geisinger Medical Center in Danville, Pa.

References

- Hamzeh, N. Sarcoidosis. Med Clin N Am. 2011;95: 1223-1234.

- Massara A, Cavazzini L, Corte, R, et al. Sarcoidosis appearing during anti-tumor necrosis alpha therapy: A new “class effect” paradoxical phenomenon. Two case reports and literature review. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 2010;39:313-319.

- Antoniu S. Targeting the TNF-α pathway in sarcoidosis. Expert Opin Ther Targets. 2010;14:21-29.

- Doty J, Mazur J, Judson M. Treatment of sarcoidosis with infliximab. Chest. 2005; 127:1064-1071.

- Wallis R, Ehlers S. Tumor necrosis factor and granuloma biology: Explaining the differential infection risk of etanercept and infliximab. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 2005; 34:34-38.

- Mitoma H, Horiuchi T, Tsukamoto H, et al. Mechanisms for cytotoxic effects of anti-tumor necrosis factor agents on transmembrane tumor necrosis factor α-expressing cells. Comparison among infliximab, etanercept and adalimumab. Arthritis Rheum. 2008;58:1248-1257.

- Utz JP, Mazur JE, Judson MA. Etanercept for the treatment of stage II and III progressive pulmonary sarcoidosis. Chest. 2003;124:177-185.