As a manifestation of hyperuricemia, inflammatory bullous lesions have rarely been described in the past century. A more classic presentation of hyperuricemia is acute inflammatory gouty arthritis, characterized by the deposition of monosodium urate crystals. Other complications of chronic untreated hyperuricemia may include polyarticular arthritis, tophus formation and possible chronic destructive lesions of the bone, leading to permanent disability. Cutaneous tophus formation is one possible manifestation of chronic hyperuricemia and can be associated with acute inflammatory changes, such as a gouty cellulitis and, rarely, bullous lesions.

Case

An 87-year-old woman with a history of untreated polyarticular gout was admitted to the hospital due to acute pain in several joints, including both hands and her right foot, with spontaneous formation of new blister-like lesions on the hands. Her past medical history included treatment with torsemide for congestive heart failure from ischemic cardiomyopathy, coronary artery disease, type II diabetes mellitus, hyperlipidemia, hypertension, atrial fibrillation with embolic stroke and chronic normocytic anemia. She also had a history of previously untreated gouty episodes occurring over the previous eight years.

Figures 1A & 1B

Fig. 1A: Creamy, yellow-hued bullae present over the DIP of the second digit of the right hand; and Fig. 1B: DIP of the fourth digit of the left hand with associated polyarticular synovitis. Tophi are seen overlying the PIP of the second digit.

Upon presentation to the hospital, she was afebrile with normal vital signs. She had podagra of the right great toe, and synovitis of the MCPs of multiple joints of the hands, in an asymmetric fashion. She demonstrated multiple cutaneous tophi, as well as multiple warm, tender, erythematous tophaceous lesions overlying the distal interphalangeal (DIP) and proximal interphalangeal (PIP) joints. The patient confirmed that these tophi are typically not inflamed and have been present for several years. However, she had two new lesions overlying the right second DIP and left fourth DIP, which were exquisitely tender, and had a tense, bullous appearance and texture with a creamy, yellow-white discoloration overlying an erythematous base (see Figures 1A and B).

She had a white blood cell count of 22,200/µL, hemoglobin of 10.5 g/dL, platelet count of 688,000/µL. Her renal function was within normal limits, and her serum uric acid level was 12.5 mg/dL. Radiographic examination of the feet and hands (see Figure 2) showed multiple destructive, erosive lesions with overhanging edges, consistent with a chronic, erosive, gouty arthritis.

Figure 2: Radiograph of the Right Hand

Note the erosive change (arrow) seen at the head of the proximal phalanx, characterized by its sharp, overhanging edges. Soft tissue swelling can be seen in associated acute inflammatory lesions.

Due to the hematologic abnormalities and the duration of symptoms, colchicine was withheld. She was placed on intravenous solumedrol 40 mg daily, with the intention of tapering the dosage. Initial urate-lowering therapy was deferred until resolution of the acute inflammatory presentation. After 48 hours of IV solumedrol therapy, there was complete resolution of the podagra and polyarticular inflammatory arthritis. However, the bullous lesions remained remarkably tender and continued to expand over the next 24 hours. No new bullous lesions developed, but there was clear increase in size (see Figure 3) of the initial bullae.

Ultrasonography of the small joints of the hands was performed, including the dorsal aspect of the third DIP, where the bullous lesion was located. Ultrasound imaging (see Figure 4) demonstrated a classic cutaneous appearance of “wet sugar clumps” of tophaceous gout just under the surface of the bullous lesion.

The larger of the two lesions was aspirated (see Figure 5), and coarse, granular liquid with the consistency of wet sand was drained. The bullous lesion was rinsed with saline after aspiration and wrapped. Within one day, the patient had significant reduction in pain and tenderness of the aspirated bullous lesion. The same was done for the other lesion with rapid relief, allowing further tapering of corticosteroid therapy and resolution of the progressive inflammatory skin changes. Polarized light microscopy (see Figure 6) demonstrated dense clusters of needle-shaped monosodium urate crystals, with a negatively birefringent appearance.

Discussion

Figures 3A & 3B

Fig. 3A: Enlargement of the creamy, yellow-hued bullae present over the DIP of the second digit of the right hand; and Fig. 3B: DIP of the second digit of the left hand.

Gout, considered the most common form of inflammatory arthritis, affects nearly 4% of the adult population in the U.S.1 Recurrent and exquisitely tender mono- or oligoarticular inflammation is the classic manifestation of the disease, with episodes often resolving within several days, but possibly extending up to weeks in the acute phase.

Examples of gout have been thoroughly documented for centuries and appear to be on the rise in developing countries, as hyperuricemia associated with the metabolic syndrome continues to increase.1,2 Factors contributing to this include dietary changes, with new light being shed on the effects of fructose intake on the risk of developing gout. Surprisingly, fruit juice and other sugar-sweetened beverages appear to carry a higher relative risk of developing incident gout than the consumption of purine-rich meats, classically thought of as the primary culprits of increased dietary urate burden, contributing to hyperuricemia.1 Other factors increasing the risk of incident gout include medications, particularly thiazide and loop diuretics, which contribute to hyperuricemia.1,2

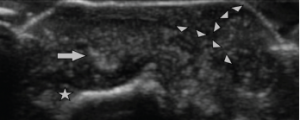

Figure 4: Ultrasound Image of the Bullous Lesion

Dorsal transverse view of the right second DIP. Note the “wet sugar clump” appearance (arrowheads) of the tophaceous material extending to the outer layer of the lesion. Extensor tendon (arrow) is seen overlying the distal phalanx (star).

Hyperuricemia, defined as the point at which serum uric acid levels exceed the threshold for saturation of approximately 6.8 mg/dL, will result in crystalline deposition of monosodium urate within tissues.2 Monosodium urate (MSU) crystals are responsible for starting the inflammatory cascade that is the hallmark of an acute gout attack. MSU deposition, destabilization and reabsorption within joints stimulates release of IL-1β from mononuclear phagocytes though activation of the NLRP3 inflammasome, resulting in local and systemic inflammatory changes, as well as a dramatic local hypernocioception.2 The classic inflammatory arthritis is associated with infiltration of neutrophils into the synovial membrane in response to the inflammatory cascade that follows.2

Chronic hyperuricemic states result in the formation of tophi, dense MSU deposits that often form in joints and also in subcutaneous tissues.3 Due to the crystalline nature of the disease, it’s tempting to consider these as biologically inert lesions outside dramatic inflammatory episodes. But the chronic inflammatory response to MSU deposition consists of granulomatous formations of CD68+ macrophages encasing the crystalline MSU core described by Dalbeth et al, with a fibrovascular zone containing plasma cells and few CD8+T cells and CD20+ B cells surrounding the middle layer, or corona, of macrophages and scattered osteoclasts.

Figure 5: Aspirate of the Bullous Lesion

A thick, chalky aspirate was withdrawn from within the bullous lesion, with granular material having the consistency of wet sand in a serosanguinous suspension.

IL-1β is highly expressed in the corona of macrophages in tophi, which appear to be inversely related to the chronicity of the lesion.3 TGFβ is also simultaneously expressed by macrophages in the same lesion, supporting the chronic inflammatory balance that is being regulated locally by macrophages involved in the granulomatous sequestering of MSU crystal deposits to form tophi. What the chronic tophaceous lesion lacks is the profound neutrophil response, which characterizes an acute gouty attack. However, the expression of IL-1β in the seemingly latent phase demonstrates the chronic inflammatory nature of MSU deposition from the hyperuricemic state.3

Cutaneous manifestations of hyperuricemia have classically been described as variations of tophus formation, with dense conglomerations of MSU depositing in the skin. Within the cutaneous spectrum of disease caused by increased urate burden, a wide range of chronic tophaceous lesions have been described, from isolated large, bulky tophus formation to a miliary appearance of scattered, small tophus formation.

Figure 6: Polarized Microscopy of the Aspirate

Negatively birefringent monosodium urate crystals aspirated from the tophaceous bullous lesion (arrow indicates polarity of light).

Among the acute manifestations, a gouty cellulitis is often seen overlying the massive inflammatory cascade within the synovium of an affected joint. Rarely have bullous gouty lesions been described. Of those that have been documented, the occurrence appears to follow a traumatic episode, similar to patterns described in chronic tophus formation.4 Other acute cutaneous tophaceous reactions, such as the abrupt development of multiple small, inflammatory, pustular gouty skin lesions, appear to be more common and have been described in several case reports.

These reactions, referred to as intraepidermal MSU deposition, have been analyzed in case series, demonstrating an average serum uric acid level of 9.59–11.4 mg/dL.5,6 A review of the handful of case reports of larger inflammatory bullous lesions, dating back to the early 1970s, shows that this is a consistent characteristic of these rare cutaneous manifestations.

What remains unclear is the pathogenesis of the larger blistering lesions, described in this report and only seven other publications. These lesions may demonstrate a profound inflammatory appearance or may develop fairly asymptomatically after trauma. Interestingly, only drainage of the lesion in our patient helped bring about resolution, which appeared to be refractory to corticosteroid therapy. This is consistent with other reports of inflammatory bullous tophaceous lesions that relented only after aspiration and drainage.4

This case demonstrates several features of acute and chronic gouty arthritis, including comorbidities, such as diuretic use, which can lead to a more profound hyperuricemic state. The effects can be profound, as evidenced by the chronic tophaceous deposits and erosive bony changes seen in this patient. The dramatic inflammatory episodes that characterize the acute gout attack have demonstrated an increasingly diverse set of manifestations, as this case highlights.

The variation of the disease manifestations continues to provide a clinical challenge. Recent guidelines made by the American College of Physicians, contrasting both the ACR and EULAR guidelines, have sparked a debate regarding the goal of management of hyperuricemia in patients with gout. With the diverging opinions, it is likely that we will continue to see a disparity in the treatment beliefs of physicians, leading to myriad manifestations of hyperuricemia. What will continue to remain true is the clinical challenge the management of various complications of the hyperuricemic state will provide, and as the trends demonstrate, we will continue to face more gout than ever before.

Mark T. Vercel, DO, is a rheumatology fellow at Franciscan Alliance, Midwestern University (Downers Grove, Ill.) transitioning into full-time practice late this summer with Franciscan Alliance.

Mark T. Vercel, DO, is a rheumatology fellow at Franciscan Alliance, Midwestern University (Downers Grove, Ill.) transitioning into full-time practice late this summer with Franciscan Alliance.

Kim Reinhart is a graduate of Michigan State University. She is currently a third-year medical student at Midwestern University (Downers Grove, Ill.), where she plans to pursue a career in primary care medicine.

Kim Reinhart is a graduate of Michigan State University. She is currently a third-year medical student at Midwestern University (Downers Grove, Ill.), where she plans to pursue a career in primary care medicine.

Amita Thakkar, MD, is a faculty member of the rheumatology fellowship program through Franciscan Alliance (Munster, Ind.), Midwestern University.

Amita Thakkar, MD, is a faculty member of the rheumatology fellowship program through Franciscan Alliance (Munster, Ind.), Midwestern University.

References

- Kuo CF, Grainge MJ, Zhang W, Doherty M. Global epidemiology of gout: Prevalence, incidence and risk factors. Nat Rev Rheumatol. 2015 Nov;11(11): 649–662.

- Terkeltaub R., 2010. Update on gout: new therapeutic strategies and options. Nat Rev Rheumatol. 2010;6(1):30–38.

- Dalbeth N, Pool B, Gamble GD, et al. Cellular characterization of the gouty tophus: A quantitative analysis. Arthritis Rheum. 2010 May;62(5):1549–1556.

- Schumacher HR. Bullous tophi in gout. Ann Rheum Dis. 1977 Feb;36(1):91–93.

- Fam AG, Assaad D. Intradermal urate tophi. J Rheumatol. 1997 Jun;24(6):1126.

- Chen I-S, Kuo H-W, Ho J-C. Intradermal urate tophi—Report of 6 cases. Dermatol Sinica. 2003;21:146–152.