Cocaine-related vasculopathy presents a unique diagnostic challenge. It resembles systemic vasculitis in clinical and laboratory findings but lacks confirmatory evidence of vasculitis on biopsy. The stigma associated with drug use often makes it difficult to obtain an accurate history. In this report, we describe four female patients with cocaine-related skin necrosis. The clinical and serological profiles in these cases led to the initial differential diagnosis of antiphospholipid syndrome, cutaneous vasculitis, cryoglobinemia, or systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE). However, skin biopsies revealed mainly microvascular thrombosis with only minimal evidence of leukocytoclastic vasculitis. These atypical histological findings, combined with a positive urine toxicology screen for cocaine, suggest vasculopathy induced by levamisole, an adulterant used as a cutting agent in cocaine.

The Cases: Patient 1

A 49-year-old black female presented to the outpatient rheumatology clinic with a five-month history of intermittent bilateral knee swelling and pain. She also noted fatigue, myalgias, painful oral ulcers, and a 20-pound weight loss. Right knee arthrocentesis revealed nucleated cells (9,720), no crystals, and negative cultures. Serological testing was significant for positive antinuclear antibody (ANA) 1:320 with a speckled pattern, an anti–double stranded DNA (anti-dsDNA) of 235.5 IU/ml (normal < 30) negative rheumatoid factor (RF), anticitrullinated cyclic peptide (anti-CCP), cryoglobulins, and normal complement levels. A lupus anticoagulant (LAC) screen was positive, but a dilute Russell viper venom time (dRVVT) confirmatory test was negative. The anti–beta-2-glycoprotein and anticardiolipin (ACL) antibodies were both negative. Inflammatory markers were notable for an elevated erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) of 63 mm/hr and C-reactive protein (CRP) of 138 U. Based on her clinical presentation and positive serologies, the patient was diagnosed with SLE. Her right knee was injected with corticosteroids, and she was started on hydroxychloroquine (HCQ) 400 mg/day.

She returned two weeks later with a new purpuric necrotic rash on both external ears and on the upper and lower extremities, accompanied by intense pain (see Figure 1). She denied any cold exposure or Raynaud’s phenomenon, but was noted to have oral and nasal ulcers. Upon further questioning, the patient admitted to using inhaled cocaine prior to the development of her skin lesions. A urine drug screen for cocaine was positive. Additional serologic testing revealed a positive antineutrophilic cytoplasmic antibody (ANCA) of 1:320 initially and 1:640 on repeat testing. Myeloperoxidase (MPO) was 34 U (normal=negative 0–20 units, weakly positive 21–30 units, moderate to strongly positive >30 units), and anti–proteinase-3 (PR3) was 47 (normal=negative 0–20 units, weakly positive 21–30 units, moderate to strongly positive >31 units). Skin biopsy findings are shown in Figure 2 and summarized in Table 1. A presumptive diagnosis of cocaine/levamisole-associated vasculitis was made. The patient was counseled to abstain from further illicit drug use.

At the three-month follow-up visit, a more detailed evaluation of her ANCA profile by Western blot analysis revealed variable reactivity to neutrophil elastase (NE) and cathepsin G (CG) in addition to PR3 (see Figure 3). At her 12-month clinic visit, the patient stated that she had completely abstained from any cocaine use and noticed no new skin eruptions. Her old skin lesions have healed with significant scarring. She is treated with HCQ 400 mg daily for her lupus symptoms consisting of intermittent arthritis flares.

Patient 2

A 54-year-old white female with history of recurrent methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) abscesses presented to the emergency department with a history of painful skin rash, fatigue, and migratory polyarthralgias involving small joints of the hands, knees, and ankles. She worked as an exotic dancer and admitted to inhalational use of marijuana and cocaine regularly. She denied intravenous drug use. Physical exam was significant for purpuric, erythematous nonblanching macules, and patches over the flexor and extensor surface of her legs, buttocks, bilateral breasts, and left pinna, including the lobe and left cheek (see Figure 4. Necrotic skin overlying these areas along with hemorrhagic bullae was noted. A workup for endocarditis was negative. The urine drug screen was positive for cocaine. Serologic testing was significant for positive ANCA 1:320 that reacted with MPO 27, PR3 11, ESR 37 mm/hr, and CRP 82 U. The infectious screen, ANA, anti-dsDNA, extractable nuclear antigen, cryoglobulins, ACL, RF, anti-CCP antibodies were all negative, and complement levels were normal. Skin biopsy findings are shown in Figure 2 and summarized in Table 1 . They revealed vasculopathic dermatitis with intravascular thrombi, dermal abscess formation over the cheek, and leukocytoclastic vasculitis with vascular complement reactivity to type IV collagen. A presumptive diagnosis of cocaine-/levamisole-associated vasculitis was made. The patient was counseled to abstain from further illicit drug use. A two-week course of oral prednisone 20 mg daily was prescribed with dramatic improvement of her skin rash, which healed with scarring.

Three months later, the patient was readmitted with a recurrence of her painful purpuric skin eruptions following the inhalation of cocaine. This time the rash was more extensive, with areas of confluence and hemorrhagic bullae. Repeat ANCA was positive at 1:1,280 with reactivity to both MPO and PR3. ANCA analysis by Western blot performed 72 hours after the event revealed strong serum reactivity against CG and PR3 with minimal reactivity toward human neutrophil elastase (NE) (see Figure 3). The patient was treated with a four-week prednisone taper resulting in complete healing of the skin lesions. Unfortunately, she continued to have relapses associated with repeated cocaine use.

Patient 3

A 41-year-old white female with a history of hypothyroidism and hepatitis C infection presented with a painful, purpuric rash with hemorrhagic bullae on her buttocks and extremities. She admitted to having smoked marijuana laced with cocaine. The urine drug screen was positive for cocaine. The ESR was 92 mm/hr, the CRP was 135 U, the ANCA was 1:640 titer with an MPO of 49 U, and the PR3 was 81 U. Serologic testing revealed a positive ANA with a titer of 1:320, in a speckled pattern. The anti-dsDNA antibody was 190 IU/ml, and the antihistone antibody was positive. The serum C3 was 115 mg/dL (normal=85–185 mg/dL) and C4 was 6.5 mg/dl (normal=12–54 mg/dL. The LAC and dRVVT were positive. Tests for HIV antibody, cryoglobulins, RF, and anti-CCP antibodies were negative. A Western blot revealed strong reactivity against CG and PR3 and moderate reactivity against human NE (see Figure 3). The skin biopsy results are shown in Table 1. She responded dramatically to a regimen of prednisone 40 mg daily for four weeks and to cessation of illicit drug use, but was lost to follow-up.

Patient 4

A 39-year-old African-American female with a medical history of MRSA hydradenitis presented with a three-day history of a painful, violaceous, bullous rash on her face, ears, extremities, chest, and abdomen. She noted five similar episodes over the past year. The urine drug screen for cocaine was positive. The absolute neutrophil count was 1.7×103/mm3, the ESR was 61 mm/hr, the CRP was 102 U, and the ANA was negative. The initial ANCA was positive with a titer of 1:1,280; the MPO/PR3 antibodies were not detectable. A repeat ANCA six months later was positive with a titer of 1:2,560 and a positive MPO of 34 U and PR3 of 47 U. The Western blot study showed strong serum reactivity against human NE and PR3 and moderate reactivity against CG (see Figure 3). A presumptive diagnosis of cocaine-/levamisole-associated vasculitis was made. The patient was counseled to abstain from further illicit drug use. Her skin lesions and neutropenia spontaneously resolved, but she relapsed six months later following repeated illicit drug use.

Discussion

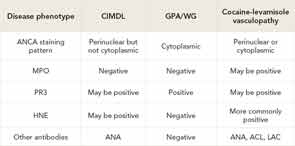

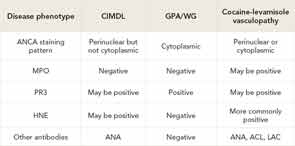

Historically, cocaine use is associated with several cardiovascular morbidities due to its vasoconstrictive and platelet-activating properties. However, cocaine use also has been linked to a wide spectrum of dermatologic and rheumatologic manifestations. Table 2 (below) highlights some the common mimics of this condition, focusing on serology and histopathology. Cocaine associated midline destructive lesions may pose a diagnostic challenge and can be confused with ANCA-associated vasculitis, because the c-ANCA test is often positive in both diseases.1,2 Cocaine has been implicated in the development of acute skin necrosis, pseudovasculitis, retiform purpura, necrotizing skin lesions, Stevens-Johnson syndrome, generalized pustulosis, and cutaneous fibrosis.3,4 Recently, a vasculopathy or pseudovasculitis associated with levamisole-contaminated cocaine use is gathering increasing interest following several case reports.1,2

The U.S. Drug Enforcement Agency reports that approximately 5 million Americans use cocaine regularly.5,6 As of 2011, about 89% of seized cocaine in the United States was tainted with levamisole (ergamisole).5-7 Levamisole potentiates the euphoric effect of cocaine, explaining its use as a cutting agent.7,8 However, the association between levamisole-contaminated cocaine use and an associated vasculopathy has only recently been noted. Levamisole is an antihelminthic agent used in veterinary medicine.6,7 It also stimulates T cells and macrophages, enhances B-cell production, and upregulates the expression of major histocompatability complex class I genes, vascular cell-adhesion molecule-1, and intercellular adhesion molecule 1, as well as the production of interferon-gamma and interleukin-2.2,6,7,9,10 Levamisole potentiates the pressor responses to noradrenaline, angiotensin, and acetylcholine, likely due to the inhibition of monoamine oxidase, catechol-O-methyltransferase, and catecholamine uptake mechanism.6, 7, 9-11 Levamisole can be detected in urine; however, it has a very short half life of about six hours, so it may become undetectable within 48 hours of exposure. Negative toxiciology testing from levamisole therefore should not be deemed as absence of exposure17.It was withdrawn from the U.S. market in 1999 due to the risk of serious side effects.2,3,5-7,9

It is strongly suspected that levamisole in cocaine induces the observed pseudovasculitis, although the exact underlying mechanism is unknown. Similar necrotic skin lesions with a predilection for face, ears, and cheeks were previously noted in children with nephrotic syndrome treated with levamisole.8,12-15 The dermal pathology demonstrated a wide variety of vasculopathic reactions ranging from thrombotic vasculitis to bland vascular occlusive disease without a true vasculitis. In addition, hypersensitivity vasculitis in superficial and deep dermis with neutrophilic infiltration and fibrinoid necrosis has been observed.4,8,12-14

In ANCA-associated vasculitides, autoantibodies are usually directed against PR3/c-ANCA and MPO/p-ANCA. However, atypical ANCAs directed against other neutrophil protein components, including CG and human NE have been reported in cases of cocaine-related vasculopathy.2,8,14,16 It is proposed that levamisole use stimulates the production of autoantibodies, including ANA, LAC, and ANCA.2,9 Whether levamisole-induced ANCAs are directly pathogenic remains to be determined.2

There are no set recommendations for the treatment of levamisole-associated vasculopathy. In many reported cases, the skin disease was self-limited and resolved upon cessation of cocaine use.2 Several of our patients received pulses or short courses of oral prednisone. Although the skin lesions are thrombotic and not inflammatory, we found that our patients responded rapidly to steroid treatment. However, there appears to be no role for chronic immunosuppressive therapy.

We suspect the frequency of levamisole-induced vasculopathy will continue to increase as clinicians become aware of the clinical presentation. The differential diagnosis of levamisole-induced vasculopathy should be entertained when faced with necrotic lesions suggestive of vasculitis. A careful history, urine drug screening, and serological testing should point one toward the correct diagnosis. The importance of recognizing levamisole-induced vasculopathy lies in the fact that cessation of use of the levamisole-contaminated drug is the key treatment, rather than immunosuppression and/or anticoagulation therapy.

At the time of writing this article, Drs. Joshi, Gupta, and Park were fellows in the division of rheumatology at Washington University/Barnes-Jewish Hospital in St. Louis. Dr. Joshi is now in clinical practice in Beaumont, Texas. Dr. Gupta is in practice in Gulfport, Miss. Dr. Pham is an associate professor at Washington University/Barnes-Jewish Hospital. Dr. Kahl is professor in the division of rheumatology at Oregon Health Science Center in Portland. Dr. Park is pursuing a third year fellowship.

References

- Peikert T, Finkielman J, Hummel A, et al. Functional characterization of antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies in cocaine-induced midline destructive lesions. Semin Arth Rheum. 2008;58:1546-1551.

- Specks U. The growing complexity of the pathology associated with cocaine use [comment]. J Clin Rheumatol. 2011;17:167-168.

- Brewer J, Meves A, Bostwick J, et al. Cocaine abuse: Dermatologic manifestations and therapeutic approaches. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2008;59:483-487.

- Walsh N, Green P, Burlingame RW, Pasternak S, Hanly J. Cocaine-related retiform purpura: Evidence to incriminate the adulterant, levamisole. J Cutan Pathol. 2010;37:1212-1219.

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. Nationwide public health alert issued concerning life-threatening risk posed by cocaine laced with veterinary anti-parasite drug. Published September 21, 2009. Available at www.samhsa.gov/newsroom/advisories/090921vet5101.aspx. Accessed July 8, 2012.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Agranulocytosis associated with cocaine use—four states, March 2008-November 2009. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2009;58:1381-1385.

- Chang A, Osterloh J, Thomas J. Levamisole: A dangerous new cocaine adulterant. 2010;88:408-411.

- Khan T, Cuchacovich R, Espinoza L et al. Vasculopathy, hematological and immune abnormalities associated with levamisole-contaminated cocaine use. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 2011;41:445- 454.

- Ullrich K, Koval R, Koval E, et al. Five consecutive cases of a cutaneous vasculopathy in users of levamisole-adulterated cocaine. J Clin Rheumatol. 2011;17:167-168.

- Zhang W, Du X, Zhao G, et al. Levamisole is a potential facilitator for the activation of Th1 responses of the subunit HBV vaccination. Vaccine. 2009;27:4938-4946.

- Spector S, Munjal I, Schmidt DE. Effects of the immunostimulant, levamisole, on opiate withdrawal and levels of endogenous opiate alkaloids and monoamine neurotransmitters in rat brain. Neuropsychopharmacology. 1998;19:417-427.

- Rongioletti F, Ghio L, Ginevri F, Bleidl D, Rinaldi S, Edefonti A, et al. Purpura of the ears: A distinctive vasculopathy with circulating autoantibodies complicating long-term treatment with levamisole in children. Br J Dermatol. 1999;140:948-951.

- Walsh NM, Noreeen MG. Cocaine-related retiform purpura: Evidence to incriminate the adulterant, levamisole. J Cutan Pathol. 2010;37:1212-1219.

- Jacob RS, Silva CY, Powers JG, et al. Levamisole-induced vasculopathy: A report of two cases and a novel histopathologic finding. Am J Dermatopathol. 2012;34:208-213.

- Davin J, Merkus M. Levamisole in steroid sensitive nephritic syndrome of childhood: The lost paradise? Pediatr Nephrol. 2005. 20:10-14. Neuropsychopharmacology. 1998;19:417-427.

- Weisner O, Russell K, Lee A, et al. Antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies (ANCA) reacting with human neutrophil elastase as a diagnostic marker for cocaine induced destructive lesions but not for autoimmune vasculitis. Arthritis Rheum. 2004;50:2954-2965.

- Kouassi E, Caille G, Lery L, et al. Novel assay and pharmacokinetics of levamisole and p-hydroxylevamisole in human plasma and urine. Biopharm Drug Dispos. 1986;7:71-89.