Take Home Points

- Mechanic’s hands are a distinct clinical feature of the antisynthetase syndrome, which comprises interstitial lung disease, myositis, arthritis, fever, and Raynaud’s phenomenon.

- A cytoplasmic staining pattern on immunofluorescence testing may provide a clue to the presence of antisynthetase antibodies.

- Anti–Ro-52 antibodies—but not anti–Ro-60 antibodies—are associated with idiopathic inflammatory myositis.

- Rituximab has been shown to be successful in patients with antisynthetase syndrome who failed cyclophosphamide or other immunosuppressive treatment in a small case series, but no studies have yet been conducted that show its efficacy as a first-line agent.

The Case

A 48-year-old man had been in his usual state of health until December 2012, when he presented to the emergency department of a hospital in Maine complaining of malaise, diffuse arthralgias and myalgias, and a three-week history of a worsening cough. A chest X-ray showed bilateral lower-lobe pneumonia. He was sent home with a prescription for azithromycin. Two days later, he returned to the same emergency room with fever to 101.5º F, chills, worsening cough, and shortness of breath. He was noted to be hypoxemic and was admitted to the hospital. Antibiotic coverage was broadened to include ceftriaxone and levofloxacin.

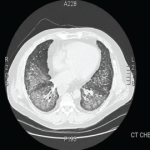

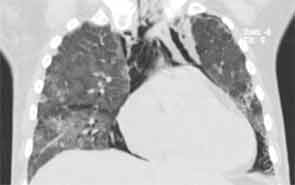

Over the next day, he became tachypneic and his oxygen saturation dropped to 79% on room air. He failed a trial of bilevel positive airway pressure (BPAP), and was intubated and transferred to the medical intensive care unit (ICU). Chest computed tomography (CT) showed diffuse bilateral infiltrates sparing only the right upper lobe. Bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) yielded 571 white blood cells (WBCs), mostly polymorphonuclear neutrophils (PMNs), ciliated epithelial cells, and pulmonary macrophages. Persistent fevers led to stepwise broadening of antibiotics, to include vancomycin, piperacillin/tazobactam, doripenem, linezolid, and rifampin. Despite these efforts, his oxygen demand continued to increase.

Empiric steroids were introduced one week into his course, initially 125 mg of Solu-Medrol every six hours, tapered to 60 mg every six hours two days later. His course was complicated by the development of pneumomediastinum. Persistent low-grade fevers and leukocytosis prompted exchange of all lines. Repeat chest CT two weeks after his admission showed extensive bilateral confluent areas of airspace disease that was felt to represent consolidative pneumonia with bilateral pleural effusions. New areas of ground-glass opacities were seen in the right upper lobe, lingula, and right middle lobe. At this time, the rheumatology service was consulted for possible acute interstitial pneumonia. Steroids were increased to pulse doses, 250 mg Solu-Medrol every six hours for one day. Intravenous cyclophosphamide was considered but deferred, given there was no clear evidence of a collagen vascular disease. He failed to improve and at this point, in early January 2013, he was transferred to the medical ICU of our hospital for further management.

His past medical history included hypertension, hyperlipidemia, gastroesophageal reflux disease, Raynaud’s phenomenon for the past five years, a history of arthritis (the details of which were unclear), and chronic back pain. He had no family history of rheumatologic disease. His medications taken prior to admission were lovastatin, aspirin, lisinopril, and ranitidine. He had no known drug allergies. He lived with his girlfriend of 12 years and worked as a chef. He had never smoked. He had no significant travel history.

On exam he was intubated and sedated. He was febrile to 103.3º F. Blood pressure was 100/60 mmHg, heart rate 60 beats per minute while on pressors. Tidal volume was set to 400 ml, respiratory rate to 35, fraction of inspired oxygen (FiO2) to 1.0, with a positive end-expiratory pressure of 14. He had anasarca with a calculated fluid overload of 16 liters. His heart sounds were regular with no murmurs. He had coarse respiratory sounds on lung exam. There was no synovitis in any joints. Thickened cracked skin was noted on the palmar surface of the thumb, index, and middle fingers bilaterally (see Figure 1).

Laboratory workup showed a WBC of 23.8, with neutrophil predominance. Arterial blood gas showed a pH of 7.23, a pCO2 of 69 mmHg, pO2 of 337 mmHg on FiO2 of 1.0. Serum creatinine was 0.95 (ref 0.8–1.3 mg/dL). Urinalysis revealed no red blood cells or protein. Creatine kinase (CK) was 80 (normal range 60–400 U/L). Liver function tests were normal except for alanine transaminase 106. Blood cultures and cultures from BAL were negative, as was the polymerase chain reaction test for pneumocystis jiroveci. He had three negative stains for acid-fast bacilli (AFB) and a HIV test was negative. The urine specimens were negative for legionella and histoplasma antigens.

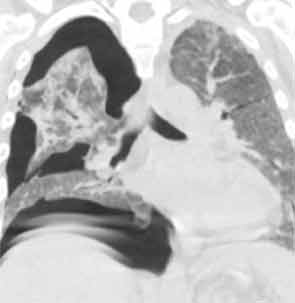

Chest CT at our hospital showed improvement in the lung consolidations but new lobular ground-glass opacities (see Figure 2). This was felt to be consistent with improving pneumonia and subsequent development of adult respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS). Steroids were held due to lack of significant improvement and concerns for worsening prognosis in late stage ARDS. All antibiotics were discontinued. An aggressive diuresis plan was initiated. Cytology from BAL returned cytopathic changes suspicious for herpes simplex virus (HSV). Acyclovir was initiated while it was unclear whether these changes represented contamination, reactivation, or active infection. His respiratory status did not improve.

Rheumatologic workup included a negative antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody test, rheumatoid factor, cyclic citrullinated peptide antibody, cryoglobulin, antinuclear antibody (ANA), dsDNA, and Scl-70 and Jo-1 antibodies. He was noted to have a positive cytoplasmic antibody with a titer of 1:160. Ro antibody was positive at 129 (normal 0–19.99). Antibodies to other extractable nuclear antigens as well as cardiolipin antibodies, beta-2-glycoprotein antibodies, and the lupus anticoagulant were all negative.

Given the presence of thickened cracked skin on the patient’s hands, which we felt to be consistent with mechanic’s hands, negative ANA, positive cytoplasmic and Ro antibodies, as well as history of Raynaud’s phenomenon and arthralgias, an antisynthetase syndrome was considered. A myositis-specific antibody panel was sent.

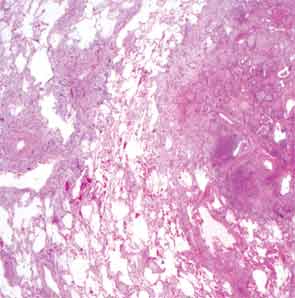

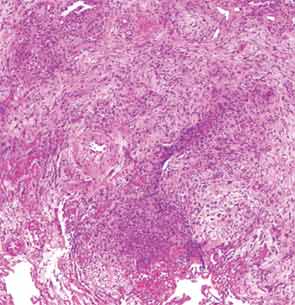

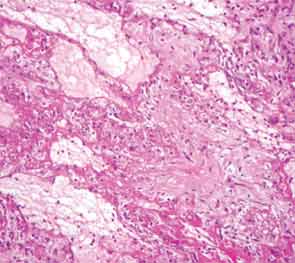

The patient then underwent a right upper-lobe wedge biopsy. This showed acute and organizing diffuse alveolar damage (DAD) with marked cytologic atypia, vascular thrombosis, collections of eosinophils, and vascular mural thickening. Hyaline membranes involved most of the specimen (see Figure 3). Immunohistochemistry for HSV showed a rare, weakly positive cell but no characteristic viral cytopathic inclusions. Immunohistochemistry for cytomegalovirus was negative. No organisms were seen on Grocott’s methenamine silver stain (GMS), AFB, Brown-Hopps, or Steiner stains. There was no evidence of malignancy.

The overall picture was that of an acute alveolar injury in an exudative and fibroproliferative phase, superimposed on an older process with organizing pneumonia by perhaps two to three weeks. Some lymphoid aggregates were suggestive of possible autoimmune etiology.

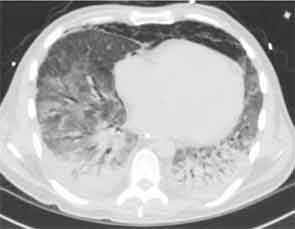

His lung biopsy was complicated by pneumothorax (see Figure 4). He required multiple chest tube placements. He underwent a tracheostomy procedure.

In mid January, two days after his lung biopsy, pulsed dose steroids were started, 1 g solumedrol IV daily for three days, followed by prednisone 60 mg daily. He was continued on acyclovir for prophylaxis for HSV reactivation. Because of persistent fevers, broad-spectrum antibiotics were resumed. Cyclophosphamide was considered, however, at the time, stains for pathogens from his lung biopsy were still pending. In this setting we worried about the added risk that a broad immunosuppressive approach with cyclophosphamide was going to pose and we chose instead to treat the patient with B-cell depletion only. He was thus started on rituximab and received 1 g IV on Day 2 of his pulsed steroid dose. A second dose of 1 g IV was given two weeks later. His respiratory status began to improve three days after the start of the immunosuppressive treatment. Over the ensuing week, he went on to have a dramatic clinical response and was able to wean off of ventilator support completely eight days after initiation of immunosuppressive treatment. The myositis-specific antibody panel returned positive for PL-7.

His tracheostomy was decannulated three weeks later. He required pleurodesis for recurrent pneumothorax, but by mid February, the last chest tube was removed. At the time of his discharge to a rehabilitation facility, his oxygen saturation was 95–97% on room air.

He has since been slowly recovering from critical-illness myopathy. In early March, he was discharged home. Prednisone has been tapered in 10-mg decrements monthly. At the end of March, we saw him back in our outpatient clinic for the first time. He had regained about 30 pounds since hospital discharge. He had nearly full strength in all extremities. He remained B-cell depleted and continued to have a remarkable sustained response to steroids and rituximab in terms of his lung disease. Figure 5 (below) shows his most recent chest X-ray.

Discussion

The antisynthetase syndrome comprises a distinct clinical subset in the polymyositis/ dermatomyositis spectrum in which patients present with the combination of mechanic’s hands, Raynaud’s phenomenon, fever, arthritis, myositis, and interstitial lung disease (ILD).1 Not all of these clinical features have to be present to consider the syndrome.

In our patient, several clinical and laboratory findings provided clues towards a diagnosis of the antisynthetase syndrome. The most intriguing finding on his physical exam was the presence of mechanic’s hands. In retrospect, our patient also had most of the other features of the syndrome, including Raynaud’s phenomenon, fever, arthritis or arthralgias, and ILD. He did not have clinical or laboratory evidence of myositis, although we might have missed subtle muscle weakness given his intubated and sedated status. Another diagnostic clue early on in his evaluation was the presence of positive cytoplasmic antibodies with a negative ANA on immunofluorescence testing. Antisynthetase antibodies localize to the cytoplasm and produce a cytoplasmic staining pattern on immunofluorescence staining for ANAs.2 While a Jo-1 antibody was negative, this prompted us to send a myositis specific antibody panel. The patient, furthermore, had a positive Ro antibody on solid phase assay testing (ELISA).

Ro antibodies comprise antibodies to Ro-52 and Ro-60.3,4 Ro-60 resides in the nucleus but loses its immunoreactivity during preparation of the human epithelial cell line–2 (HEp-2) cell substrate and therefore does not produce a staining pattern on ANA testing using the traditional HEp-2 cell substrate. The result then is a falsely negative ANA. Ro-52, on the other hand, resides in the cytoplasm and may produce a cytoplasmic staining pattern on ANA immunofluorescence testing. Whether the Ro antibody in our patient represents antibody to cytoplasmic Ro-52 or nuclear Ro-60, both of which do not produce nuclear staining on ANA testing, is unclear. We suspect that he has the Ro-52 antibody because anti–Ro-52 antibodies but not anti–Ro-60 antibodies have been detected in a subset of patients with idiopathic inflammatory myositis. His cytoplasmic staining pattern could be the result of the PL-7 antibody alone or the combination of PL-7 and Ro-52.

The PL-7 antisynthetase syndrome is the third most common of the antisynthetase syndromes (after Jo-1 and PL-12).5 Most patients have myositis. Interstitial lung disease is the second most common manifestation. To date there are only case reports and small case series on the use of rituximab in the antisynthetase syndrome. Sem et al reported on 11 patients with antisynthetase syndrome who had previously failed treatment with cyclophosphamide or other immunosuppressive treatment.6 The interstitial lung disease stabilized or improved in seven of 11 patients with the antisynthetase syndrome at six months follow-up. There was one fatal infection three months after rituximab. Otherwise, the drug was well tolerated in these patients.

No retrospective or prospective studies have yet evaluated rituximab as a first-line agent for this indication. In our patient with PL-7 antisynthetase syndrome, at three months follow-up, rituximab has proven to be successful as a first-line steroid-sparing agent.

Dr. Rastalsky is a fellow in rheumatology at Massachusetts General Hospital in Boston.

Send us Your Case Suggestion

Have you managed a patient with an unusual rheumatologic problem that you would want to present to a larger audience? Consider submitting your case to The Rheumatologist.

We are looking for interesting cases that are well written and provide useful teaching points to the reader. Send an outline of your case presentation to Simon Helfgott, MD, at [email protected], or visit www.The-Rheumatologist.org for more information.

References

- Dickey BF, Myers AR. Pulmonary disease in polymyositis/dermatomyositis. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 1984; 14:60.

- Betteridge Z, Gunawardena H, North J, et al. Anti-synthetase syndrome: A new autoantibody to phenylalanyl transfer RNA synthetase (anti-Zo) associated with polymyositis and interstitial pneumonia. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2007; 46:1005.

- Schulte-Pelkum J, Fritzler M, Mahler M. Latest update on the Ro/SS-A autoantibody system. Autoimmun Rev. 2009; 8:632.

- Bloch D. The anti-Ro/SSA and anti-La/SSB antigen-antibody systems. Uptodate.

- Labirua-Iturburu A, Selva-O’Callaghan A, Vincze M, et al. Anti-PL-7 (anti-threonyl-tRNA synthetase) antisynthetase syndrome: Clinical manifestations in a series of patients from a European multicenter study (EUMYONET) and review of the literature. Medicine. 2012; 91 (4): 206-211.

- Sem M, Molberg O, Lund MB, Gran JT. Rituximab treatment of the anti-synthetase syndrome—A retrospective case series. Rheumatology. 2009; 48: 968–971.